Kurds in Turkey

On internationalrelations.org, we have written articles on Kurdish politics in the Middle East. This piece is within a series of articles that we are writing on the politics of the various Kurdish populations in the Middle East. In this series of article, we will be examine the political conditions regarding at the Kurds in Turkey, the Kurds in Iran, the Kurds in Syria, and in the Kurds in Iraq. In this specific article, we shall discuss the relationship between the Turkish national government and the Kurdish minorities. We will discuss the history of the Kurds in Turkey, how the government has approached this group, the civil conflict that began in the 1980s, attempts at peace, and the more recent surge in violence. We will also relate the Kurdish situation in Turkey to developments in Syria.

As we shall see, there is a serious conflict currently taking place in Turkey between the government iorces and the Kurdish Worker’s Party (PKK). This is one of the major problems that Turkey is currently dealing with. However, this is not a new conflict, nor is one that has been viewed as “less serious” or “less important”. Rather, many scholars have viewed the relationship between the Turkish national government and the Kurdish minority population as one of the most important questions and issues facing Turkey. For example, Martin Abramowitz, writing the forward to the book Turkey’s Kurdish Question, in the year 1998, say of the conflict:

The ‘‘Kurdish issue’’ is Turkey’s most difficult and painful problem, one that presents a vast moral dilemma for the country. The issue, as the authors note, feeds Turkey’s continuing inflation and is the major source of human rights violations and the biggest irritant in Turkey’s relations with the European Union. Its most pronounced manifestation, the war in the southeast against Kurdish insurgents, has left more than twenty thousand dead and many hundreds of thousands displaced. Despite the massive Turkish military effort and some significant gains in coping with the Kurdistan Workers’ party (PKK) insurgency, the fighting continues after thirteen years, although it has not reached the major cities of Turkey as many have long predicted.

That quote can be as applicable today as it was in 1998. There is a long history of acnsion and violence between a Kurdish minority demanding equal rights, and state leaders seemingly unwilling to offer such concessions.

The History of the Kurds in Turkey

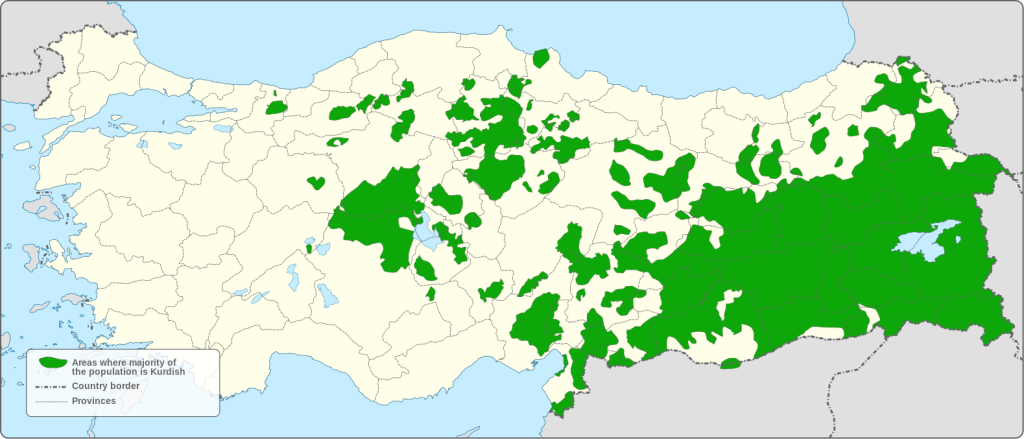

The Kurdish population is spread throughout different countries in the Middle East. The Kurds in Turkey themselves are a large percentage of the population in southern Turkey, making up anywhere from 15 to 20 million of the overall population (this is difficult to know for sure given the fact that census questions of ethnicity do not exist (Taşpinar & Tol, 2014).

Map showing Kurdish majority areas within Turkey, Kurdish Institute of Paris Map, Goran Tek-en, CC 4.0

Historically, the Kurds have lived in various Middle East empires (such as the Safavid Empire, as well as the Ottoman Empire). During the Ottoman Empire, the Ottomans categorized groups based on religion, and not ethnic differences. With regards to the Kurdish region, the Sultan had ties to the local leaders who would help oversee the areas of Ottoman control.

However, in the 1800s, due to a weakening Ottoman Empire, a number of outside countries were challenging the borders of the Empire. Because of this, the Ottomans, through various internal reforms, attempted to rebuild control in Istanbul. However, as they tried to increase power over the distant parts of the empire, they were met with resistance. One of the places where this happened was in the Kurdish parts of the empire. Here, Kurdish leaders such as “Mir Mehmet Pasha of Rewanduz and Bedirhan Bey of Cizre are the most famous” (Barkey & Fuller, 1998: 7). However, there were dozens (scholars say over 50). But what is important to note is that many of these were not under the banner of Kurdish nationalism, but rather, revolts led by Sufi tariqas” (7).

It was in the late 1800s and early 1900s that the idea of Kurdish nationalism as a political movement took hold in the Middle East. Part of this was the various ethnic nationalist movements throughout the Ottoman Empire. We saw this with the Armenians (where many Kurds also lived), among many others. Nationalism was on the rise during this period, some within the Kurdish communities then mobilizing under Kurdish nationalism (Barkey & Fuller, 1998).

The last sultan within the Ottoman Empire (Sultan Abdul Hamid) attempted to reform the Ottoman Empire back around an Islamic identity. He attempted to do so through Kurdish leaders (Barkey & Fuller, 1998). But while this was the case that an attempt at and Ottoman Islamic identity was being set, and that the Sultan was getting help in Kurdish areas (and elsewhere), Kurdish nationalist demands were already coming into place. For example, Barkey & Fuller (1998) write:

Among the first instances of direct intervention and differentiation in the Kurdish region by the imperial state in Istanbul was the creation in 1891 of Kurdish officered and soldiered Hamidiye regiments. Designed to maintain order in the eastern provinces, these battalions were eventually used by the Ottoman state in its campaign against the Armenians. In the interim, the armed and tribally organized battalions became the source of a state-sponsored division within the Kurdish community as those Kurds benefiting from state patronage and arms would antagonize and oppress those who did not. They also represented an attempt by the state inadvertently perhaps to differentiate between Kurds and non-Kurds, including Turks. The Hamidiye, just like the village guard system a century later, further strengthened tribal links among Kurds. While there is a debate over the degree of ethnic consciousness exhibited by Kurds during the latter part of the century, from the increased political activities in Istanbul and elsewhere, it is evident that something was afoot (8).

In addition, the late 1800s (1898) witnessed the first Kurdish based newspaper (which was entitled Kurdistan) from the Kurdish diaspora in Egypt. The Kurdish leaders used both nationalism and secular liberalism as their tools against the Ottoman Empire in the early 1900s. For example, “The first nationalist organization, the Kurdish Society for the Rise and Progress, was formed in 1908” (Barkey & Fuller, 1998: 8).

During World War I, the Kurds fought with the Ottoman Empire against the British, French, and Russians. Having lost the War, the Ottomans also lost the territory that once belonged to them, as well as their political voice: a new political era was in place, and the Kurds, at least at first, looked to benefit from this. However, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk urged many of the Kurds to help him fight outside forces in order to establish a new Turkey were everyone would be equal. In addition, “Kemal had even envisaged, according to some accounts of his speeches and conversations with journalists, that where Kurds were in a majority they would govern themselves autonomously” (Barkey & Fuller, 1998: 9). Now, this is not to say that there were no rebellions, as there were (such as the Ko ̧cgiri rebellion, among others). However, Mustafa Kemal was able to fight with the Kurds (Barkey & Fuller, 1998) to re-define the borders into the new Turkish state.

The Kurds in Turkey After World War I

Following World War I, in the 1920 Treaty of Sevres (that divided the post-Ottoman territory in the Middle East), Armenia was to be its own state, and the Kurdish region of the Middle East would have autonomy, with a possibility of independence (Barkey & Fuller, 1998). Within Turkey, Mustafa Kemal did little to uphold any notions about Kurdish autonomy within Turkey. Plus, in his quest to build Turkish nationalism, he repressed any other notions of identity within the state. This went as far as official citizenship. In order for one to have citizenship, they had to identify themselves as Turkish, and not any other ethnicity (such as Kurdish or other identities). The scholars Barkey & Fuller (1998) argue that “Here then the seeds for eventual Kurdish dissatisfaction were planted: In a state now officially defined as ‘‘Turkish’’ the Kurds were not Turks, and only by giving up their ethnicity could they be treated as Turks. It is clear that the leaders of the Kemalist regime perceived unintegrated, unturkified Kurds as both a backward element and a potential threat to the integrity of the modern state they were intent on constructing” (11). Not only that, but Mustafa Kemal also challenged the other means of Kurdish rebellion in the past, Islamic (and Sufi) identities (Barkey & Fuller, 1998) with his emphasis of secularism in Turkey.

Thus, ever since before Ataturk, the Kurdish population has attempted to fight for equal rights in Turkey. Numerous rebellion movements were formed following the coming to power of Mustafa Kemal. However, all of them were put down by the government forces. One in particular shaped the conflict that we still see today. Following the put down of the Shaykh Said rebellion, the government continued to rely on violent repression instead of dialogue and diplomacy with the Kurds (Barkey & Fuller, 1998). With the 1930 and 1937-1938 Kurdish rebellion movements, the end response was the same: the government used violence to quell any such uprisings.

In addition, through assimilation, they attempted to remove ideas of separate non-Turkish Kurdish identities from the country. Part of Ataturk’s concern was that if some members of Turkey viewed themselves as anything but Turkish, that this would potentially weaken the country as a whole (Barkey & Fuller, 1998). While this worked to an extent, it was not as effective in the south eastern parts of the country were the Kurds largely lived. There were many reasons why Ataturk’s policies were not as effective in the Kurdish regions. As Barkey & Fuller (1998) explain, “[a]ssimilation had its limits; those limits were imposed by geography (the remoteness of the region), economics (the relative backwardness of the region making it easy for it to be economically ignored), or the lack of resources (the Turkish government’s limited resources proving insufficient for the massive task it confronted in educating and integrating the Kurdish regions’ inhabitants). Today the southeast and east are still filled with families unable to speak any language but Kurdish. However, the assimilationist policies of the state also had a reverse effect: They set into motion—albeit slowly—a process of constructing a new sense of Kurdish national identity” (13).

The Kurds in Turkey after Ataturk

After Ataturk’s death, the single Republican Party faced electoral challenges, and a defeat, at the hands of the Democrats in 1950. However, while this made the situation slightly better for the Kurds, it in no way reversed the course that Ataturk initially set with regards to identity issues in Turkey. While more policies related to Islam in society were re-introduced, there was little national level support for a reconsideration of separate minority rights for ethnic groups (such as the Kurds). And while they did allow more open space for political voice, this did not last long, which in turn further alienated the Kurdish minority. For example, “The Democrat Decade (1950–1960) was also notable for the new and relative freedom of expression that allowed all, including Kurds, to articulate their griev- ances. The Democrats would ultimately succumb to the authoritarian tendencies of their predecessors and the civil and military elites’ unease with the Democrats’ perceived disregard for them. The decade culminated, from the Kurdish point of view, in one of the more significant of trials. Forty-nine prominent Kurdish intellectuals were tried for sedition, and the government formed by the military coup that overthrew the Democrats in May 1960 quickly arrested some 484 Kurds and banished 55 aghas to western provinces (Barkey & Fuller, 1998: 14).

And thus, for decades, whether it was Ataturk’s regime, the Republicans after him, the Democrats, or groups following the 1960 coup, or the 1980 coup, the Turkish government has continued denied the Kurds in Turkey equal rights. This, coupled with the return of Kurdish leader Molla Mustafa Barzani (and with that a rising Kurdish nationalist movement) led to increased hostilities between Kurdish rebel forces, the Kurdish minority population, and the Turkish government. In fact, 1960s and 1970s were a period that witnessed the rise of Kurdish parties such as the Eastern Revolutionary Cultural Hearths (DDKO) (1969), which then in part led to other groups such as the Kurdish Worker’s Party (PKK) (Barkey & Fuller, 1998).

The Formation of the Kurdish Worker’s Party in Turkey

As mentioned, the national governments did little to offer equality to the Kurds in Turkey. Then, in 1980, with a military coup, the government viewed the Kurds as a political problem. However, by banning political parties, scholars argue that this in turned created a space that others used in the creation of military resistance groups (Barkey & Fuller, 1998). In 1984, the Kurdish forces known as the Kurdish Worker’s Party (the PKK) was established. The PKK has attempted to gain increased rights for the Kurds in Turkey. However, there has been a long and violent civil conflict in Turkey because of these issues, where, “The PKK’s insurgency has blown hot and cold since the early 1980s. It has led to some 40,000 deaths in those years” (Tharoor, 2016), and many more who have suffered due to the Kurdish insurgency and government response (Barkey & Fuller, 1998).

There have been recent attempts at resolving grievances, but given the Syrian conflict, and rising tensions in Turkey, there has been little progress with regards to a peaceful political solution to the questions regarding political authority for the Kurds in Turkey.

Again, historically, the Turkish governments throughout the decades have done very little to offer rights to the Kurdish minority in Turkey. Beginning with Turkey’s first leader following World War I, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, he embarked on a series of nationalistic pan-Turkic type of policies, which did come at the expense of minority rights for groups such as the Kurds in Turkey. In addition, leaders throughout the decades have provided little when it came to autonomy, language or culture rights, or help with employment for the Kurdish minority.

That is why some have been hopeful, at least until late 2015. To them, historically, Recept Tayyip Erdogan (of the AKP) has at least been more supportive of Kurdish rights compared to his many predecessors. It has been argued that “Erdogan has done more for Turkey’s Kurds than any other leader in the history of the modern Turkish republic, which for decades refused to recognize the existence of Kurds as a distinct ethnic group and restricted their ability to learn, speak and write their language” (Tharoor, 2015).

Kurds in Turkey: Attempts at a Negotiated Peace

As mentioned, in recent years, Erdogan has moved away from the tough military stance Turkish leaders have generally taken towards the Kurds. In 2009, for example, the Turkish government entered secret talks with the PKK. However, with the 2011 elections on the horizon, violence broke out again between the government and PKK forces. Then, in 2012, another attempt at negotiations took place. These differed from the ones in 2009 in that the public was notified about them. Here, the Turkish National Intelligence Organization (MIT) was speaking with the PKK (Taşpinar & Tol, 2014).

In fact, many have given Erdogan and the AKP credit for reversing course on politics that traditionally ignored the Kurdish minority. For example, during the rule of Erdogan and the AKP, individuals have had the option of studying the Kurdish language in schools (which is different than having lessons offered in Kurdish). Furthermore, they allowed the formation of a state-owned Kurdish-language television station. In addition, there were other reforms in the 2013 “Democratization bill” passed by the government. Here, along with the granting of the Kurdish language to be used in private schools, “[t]he package would also make it legal for Kurdish and other minority languages to be used in electoral campaigns, for the old names of Kurdish villages in Turkey’s southeast to be reinstated and for the legal use of letters such as Q, W, and X, that are used in Kurdish but not in Turkish,. Additionally, the morning oath recited by Turkish schoolchildren at the beginning of every school day, which reads “I am a Turk, I am correct, I am hard-working,” would be removed” (Taşpinar & Tol, 2014: 5).

For many Kurds in Turkey, these concessions have been few and far between. While having the possibility of learning Kurdish as an elective is welcoming, for most, it is far from enough. Again, they specifically want the government to allow public schools to be taught in Kurdish. This is also viewed as “a polarizing issue because it may put an end to the traditional policy of forcefully assimilating Kurds into Turkish society and pave the road for multiculturalism in Turkey. The debate has also raised the possibility of some form of autonomy for the Kurds, an idea that runs deeply against the unitary nature of the Turkish republic” (Taşpinar & Tol, 2014: 2). Furthermore, the Kurds are unhappy with the way the government has defined terrorism, nor did it change the high ten percent threshold for electoral representation (Taşpinar & Tol, 2014) (although the HDP has been able to clear that mark in the past two elections).

Up until events last summer (2015), there was more hope that the government and the Kurds would be able to establish peace based on negotiations. The hope was that the PKK would stop their military fight, and in turn, the Turkish government would offer additional cultural rights, and an increase in some form of more local rule (Taşpinar & Tol, 2014) (whether this would be “autonomy” or not is a question that has yet to be answered). In addition, “The broad outlines of the agreement between Öcalan and the MIT include ceasefire declaration by the PKK, the release of Turkish hostages held by the PKK and a withdrawal into Northern Iraq after laying down their arms. In return, the Turkish government is expected to craft legislation to overhaul the definition of terrorism, which would pave the way for the release of hundreds of imprisoned Kurdish activists. As part of settlement talks, the PKK declared a ceasefire in March 2013 and in May began its withdrawal from Turkey toward its camps in northern Iraq” (Taşpinar & Tol, 2014: 4).

However, given the recent and ongoing civil conflict in Syria, as well as stalled talks in Turkey, the situation now with regards to the Kurds in Turkey and the Turkish government is worrisome and far from peaceful.

The Recent 2015-Ongoing Kurdish Conflict in Turkey

Given an inability to negotiate a peaceful resolution with the Kurds in Turkey, patience has seemed to run thin with the different sides. For the Kurds, they have been frustrated with what feel is a lack of serious willingness by the Turkish national government to offer real reform for the Kurds. In fact, this can be seen by the establishment of the newer People’s Democratic Party (HDP) in Turkey. The HDP–while a Kurdish minority party, also represents other minority groups, and has a strong following in Turkey; in the recent June 2015 Parliamentary elections, the HDP reached the very high 10 percent threshold (winning 13.1 percent of the vote) to have seats in the Turkish parliament; this strong showing gave them 80/555 positions (Uras, 2015). However, because of an inability to form a coalition government new elections were held in November of 2015. In these elections, and in the wake of the terror attack in southern Turkey, Erdogan and the AKP were able to gain the most seats in government, but not a supermajority–“the 330 MPs a ruling party needs to be able to call a referendum on changes to the country’s constitution” (Henley, Shaheen, & Letsch, 2015). In the November 2015 elections, the AKP won 317 seats, which has allowed them to form a government without outside support. The HDP won 10.8 percent of this vote, leading to 59 seats in parliament (Henley, Shaheen, & Letsch, 2015).

However, while some have addressed their frustrations through the electoral process, others within the Kurdish population have moved to more military methods to combat what they have seen as decades of discrimination. For example, the recent conflict in southern Turkey began in July of 2015, following the Islamic State suicide attack in Suruc killed 33 individuals (Lepeska, 2015). Following this attack, violent Kurdish rebels killed two Turkish policeman, which resulted in a military response by the Turkish government and forces.

The Turkish government and violent separatist members from the Kurdish Worker’s Party (PKK) have intensified in recent months. Ishaan Tharoor (2016) of the Washington Post describes the intensifying conflict between the PKK and the Turkish government in in southern Turkey by saying: “In the heart of the ancient city of Diyarbakir, behind its historic black-stone walls, security forces have been engaged for weeks in clashes with the youth wing of an outlawed Kurdish separatist group. Whole neighborhoods have been sealed off under curfew; tens of thousands of people have been forced to flee. The mini-rebellion has been echoed elsewhere in Turkey’s restive southeast, a region that is home to a majority Kurdish population and that has been in the grips of a low-level civil war since tensions flared last summer. The violence is likely the worst seen in the past two decades.”

Diyarbakir is continuing to be at the heart of the conflict between the Kurdish PKK and the Turkish military. There have been many incidents that have only fanned the flames of the fire that is the civil war in Turkey. For example, in October of 2015, ” Halil Tuzuner, a 31-year-old construction worker, was on his roof tending to his pigeons when a bullet from a Turkish military assault team on the street below pierced his back and took his life. His stunned, pregnant wife Hulya found him minutes later” (Lepeska, 2015). These sorts of events have furthered the tensions between the Kurds in Turkey and the government. Writing in late January 2016, Lepeska (2016) explains that “For two months now, the heart of Diyarbakir, a city of a million people and the de facto Kurdish capital of Turkey, has been under 24-hour curfew and near-constant military assault. Some 20,000 people have fled, 1,500 shops have closed or been destroyed, and 10,000 people have been put out of work, according to local estimates.”

Since the Kurds in Turkey were unable to establish any official autonomy through a brokered peace agreement with the national government, some are turning to violence in their attempts to gain self autonomy from the government. As a result the Turkish military has not only been fighting the Kurdish Worker’s Party in southern Turkey, but they have also established strong a military presence in Kurdish majority towns such as Cizre (Tharoor, 2016).

What is very sad is that the Kurdish civilian population is caught in unlivable conditions in cities such as Diyarbakir. For example, Halil’s brother Aziz shared the frustration that many in southern Turkey feel with the conflict, saying that “Both sides are just playing for their own nationalism, and both have their reasons,” he said. “They might be right, they might be wrong – but both sides are killing people. And we, the people who live here, are in the middle of it. The minute we stop moving, we become targets” (Lepeska, 2016).

Overall, the numbers of police and Kurdish rebel forces killed in this civil war has been in the hundreds each, with suggestions that earlier numbers were over 200 Turkish police have died as a result of the fighting, as well as 500 rebel deaths (Tharoor, 2016) (with some reports saying the rebel death rate is over 600) (Lepeska, 2016) (as we discuss later, the numbers have increased greatly). As mentioned above, there have also been civilian casualties, with over 200 noncombatants killed, 33 of them being children (Lepeska, 2015). There are also over 100,000 people who have had to leave their homes as a result of the fighting.

There have been relatively recent attempts at trying to come to a peaceful solution to the whole situation regarding representation for the Kurds in Turkey, however, this fell through in 2015. And thus, currently, the violence in southern Turkey continues to carry on. Furthermore, some have argued that the Turkish government is continuing to make the situation worse. As Lepeska (2016) writes that the “…chances of the situation improving are slim…Turkey extended the curfew to five new neighbourhoods in Sur, after which dozens of families were seen lugging their belongings through the old city’s massive, UNESCO-listed stone walls, heading for safer ground. Among Kurds in Diyarbakir, the consensus seems to be that, rather than undermining the fighters and muting anti-Turkey sentiment among Kurds, Ankara’s recent operations in the southeast have inflamed it” (Lepeska, 2016). Amnesty International (2016) has noted (in December, 2016) that 24,000 residents displaced could not yet return to their homes in Sur.

Amnesty International writes that: Despite military operations ending in March 2016, part of Sur remains under curfew and residents are not allowed in. Some houses have been so badly ransacked or damaged that they are now uninhabitable. Furthermore, some houses have been demolished by the authorities without the residents even being consulted, or shown any damage assessment to justify doing so.”

Some have also argued that the conditions are being used for radicalizing the youth. As Tharoor (2016) explains, “resentment and anger is festering on the streets of Diyarbakir and other majority Kurdish cities. The city boasts a huge cemetery for Kurdish youth who have gone off to fight across the border in Syria. A radicalization has set in.” Tharoor (2016) also quoted Abdullah Demirbas, who used to be the Mayor of Sur, who said: “”Many residents of these towns are poor families who were forced to flee the countryside when the conflict between the Kurds and the Turkish state was at its peak in the 1990s.” He also said that “Those who are digging trenches and declaring ‘self-rule’ in Sur and other cities and towns of southeastern Turkey today are mostly Kurdish youths in their teens and 20s who were born into that earlier era of violence, poverty and displacement, and grew up in radicalized ghettos.” Vecdi Erbay, who is a long time Kuridsh journalist echoed similar statements, saying that “”Everything changed with these kind of operations, especially among the people in these neighbourhoods[.]” “Now there’s more anger. Also, these fighters getting killed, and their bodies in the street, just lying there, for days – this is something people won’t forget” (in Lepeska, 2016).

Human Rights Violations in the Kurdish Conflict in Turkey

There are many human rights violations that have been reported as a result of the increase in violence between the Turkish government and the Kurdish armed forces in Turkey. The Turkish government has been said to have “carried out massacres of civilians and extrajudicial killings” (Rosenfeld, 2016). Part of the problem however has been to find out exactly how how many violations have been committed because the Turkish government has restricted access and information; human rights groups have not been able to view areas in southeastern Turkey, nor have they been given access to autopsies (Rosenfeld, 2016).

In addition, “Rights groups and critics of the Turkish government accuse the state of denying civilians stuck in the siege adequate access to medical care. On Tuesday, the top human rights official at the United Nations also urged Ankara to investigate an incident that occurred last month, which involved the apparent shooting of unarmed civilians, leading to a number of casualties. Video footage appeared to show a group of civilians moving in front of an armored military vehicle before they “were cut down by a hail of gunfire,” said Zeid Raad al-Hussein, the U.N. high commissioner for human rights” (Tharoor, 2016). The Turkey government denies that they are restricting aid to civilians. In fact, Turkish President Erdogan suggested that “They [the Kurds] are deliberately not bringing the wounded out” (Tharoor, 2016).

Other Turkish Human Rights Violations

Along with human rights violations committed in the Kurdish majority areas of Turkey, the Turkish government has also carried out a number of other rights abuses against those that they view as sympathetic or supportive of the Kurdish cause. For example, the Turkish government has arrested a number of journalists the government views as supporting Kurdish forces. Specifically, “Zeki Karakuş, the owner of a local news website Nusaybin Haber (Nusaybin News), was arrested on December 1 on charges of “making propaganda for a terrorist organization,” his lawyer, Gülistan Duran, told CPJ. On December 15, Deniz Babir, a journalist with the Kurdish-language daily Azadiya Welat, was arrested on charges of belonging to a banned group, reports said. And on December 16, Beritan Canözer, a reporter with the women’s news agency JİNHA, was arrested while covering a protest in the southeastern city of Diyarbakır, on charges of aiding a terrorist organization, local press reported” (Committee to Protect Journalists, 2015).

They also reported that “Karakuş’s lawyer, Duran, said the journalist was summoned to a police station in the Nusaybin district of Mardin province in southeastern Turkey. When Karakuş arrived, authorities brought him before a court on accusations of “making propaganda for a terrorist organization” through the media, Duran told CPJ. The court sealed the investigation into Karakuş, the lawyer said, which has prevented her from establishing the exact charges and reviewing evidence authorities say they have against her client. Karakuş, whose website focuses on pro-Kurdish local news, is being held in pretrial detention at the Mardin E Type closed prison.”

Furthermore, “Separately, Babir was arrested in the Sur district of Diyarbakır while reporting on clashes between Turkish security forces and the Patriotic Revolutionary Youth Movement (YDG-H), a branch of the PKK, local press reported. CPJ’s review of court files showed that he was ordered into pretrial detention on accusations of being a member of the PKK, which is banned in Turkey. The journalist’s lawyer, Resul Tamur, told CPJ Babir denied being part of the PKK but admitted to a second charge of carrying false identification. According to Tamur, police questioned the journalist about his work. Babir is being held in Diyarbakır D Type prison” (CPJ, 2015).

There have been other arrests against journalists that the government views as supporting terrorists. For example, “Four other journalists–Ferit Dere and Elifcan Alkan of the pro-Kurdish daily Azadiya Welat, and Pınar Sağnaç Kalkan and Savaş Aslanwere of the pro-Kurdish political magazine Özgür Halk (Free People)–were arrested alongside Babir and released, reports said. According to the pro-Kurdish Dicle News Agency, Dere said police questioned all four about their reporting and confiscated their cameras, notes, and voice recorders. The equipment was not returned, he said” (CPJ, 2015).

Furthermore, along with the arrests of journalists, the Turkish national government has also went after academics. Mesut Hasan Benli of Hurriyet Daily News reported that the Turkish government arrested Ankara University political science professor Dr. Reşat Barış Ünlü. According to reports, Ünlü “asked students to compare a 1978 leaflet by Öcalan with a more recent piece from 2012 in terms of its implications for Turkey’s Kurdish question.” The specific test question read: “Compare Abdullah Öcalan’s 1978 leaflet ‘The Manifesto of the Path of the Kurdistan Revolution’ with his 2012 piece entitled ‘Democratic Modernity as the Construction of Local System in the Middle East’ with regard to their stances on concepts and phenomena such as colonialism, the nation-state, revolutionary violence and democracy” (Benli, 2016). The government viewed this as an attempt to “legitimize” Öcalan’s (and the PKK’s) views (Benli, 2016).

Moreover, there has also been continuing tensions between the AKP and the HDP party. For example, it was reported on May 2nd, 2016 that in late April, a physical fight broke out between members of the AKP and the HDP in parliament. The fight broke out due to a controversial bill the AKP is putting forward that would allow parliament members of the HDP to no longer have political immunity, which could open them up for prosecution for what Erdogan and the AKP views as being tied to the PKK. According to reports, “Scores of deputies crammed into a committee room to debate the bill, according to a Reuters reporter in parliament. Tempers flared and some deputies started shoving each other. As punches and kicks flew, a few suited parliamentarians launched themselves into the melee from a table. Others threw water at each other and at least one person could be heard taunting opponents by shouting, “Come on, come on” (Solaker & Dikmen, 2016).

Thus, the government is cracking down not only on Kurdish fighters, but also on the Kurdish minority in Turkey, as well as journalists and academics whom the government views as some threat.

The Relationship between the Kurds in Turkey and the Kurds in Syria

It is difficult to examine the question of Kurdish politics in Turkey without also understanding developments regarding the Kurds in Syria. As of this writing (in February of 2016), the Kurdish rebel forces have had some military victories in Syria, thus being able to take over and control land mass in the country. This group, the Democratic Union Party (PYD) (which as an offshoot of the PKK) has been able to advance in parts of Syria as they fight ISIS forces.

A number of the Kurds in Turkey–and those on the border with Syria–have been willing to fight on behalf of the PYD, or have supported PYD efforts in Syria.

What makes matters worse for the relationship between the Turkish government and the Kurds in Turkey is that neither sides trusts the other as it pertains to goals and interests in Syria. For the Kurds, there have been statements made, and overall concerns that Erdogan and the government are actually a willingness to allow the Islamic State to go after Kurdish forces. And while Erdogan vehemently denied such claims, many argue that the point here is that some within the Kurdish population believe this, which shows how the different sides view one another (Tharoor, 2015). And for the Turkish government, they are very worried about the rising power of the PYD in Syria. They believe that additional military victories in Syria could embolden the PKK in their own country in either increasing their own militant activities in the south, or, another threat could be that if the Kurds in Syria are able to establish their own territory (either through military gains or through a negotiated settlement), then the Kurds in Turkey may want to join with them in forming an autonomous region.

Taşpinar & Tol (2014) explain how the situation in Syria might actually be strengthening support outside the country, as well as calls for a Kurdish state when they explain that:

The Arab uprisings have fed Kurdish national ambitions in the region. Kurdish nationalists now think that the Kurdish political movement in Iraq, Turkey and Syria is on the verge of a historic breakthrough. Capitalizing on the regional chaos and deteriorating relations between Ankara and the Assad regime in Syria, the PYD took de facto control of parts of northern Syria. It possesses a well-trained militia and a clear political agenda for the future of Syrian Kurds in the form of territorial autonomy at a minimum. This is potentially a development that strengthens maximalist demands among some PKK hardliners in Turkey. Even if the PKK agrees to withdraw from Turkish soil, it may continue to operate in northern Syria. So a deal struck between Ankara and the PKK must address the PYD/PKK presence in Syria, adding further complication to an already arduous process (4).

In addition, Turkey is also concerned about the potential influx of Syrian Kurdish fighters into Turkey. While “[t]he country’s 500-mile border with Syria has become a permeable barrier due to the government’s policy of abetting rebels battling the Assad regime[,]… [b]ut border flows go both ways. Support from Syria’s well-organized and well-armed pro-PKK Kurds could fuel the fighting in Turkey, complicating the government’s efforts not only within Turkey itself, but also in Syria where Turkey-backed proxy groups operate near Kurdish areas in their fight against the Assad regime. For the first time, Turkey risks a two-country Kurdish insurgency” (Cagaptay, 2015).

It is for these reasons that Erdogan and the Turkish government are adamant about not allowing the Kurdish forces in Syria a seat at the negotiating table when talks between the Free Syrian Army forces and Bashar Al-Assad and his government begin. Furthermore, on February 10th, 2016, Erdogan made some critical remarks against the United States for what Turkey viewed as their support for the Kurds in Syria. For Erdogan, the unwillingness of the United States to label the PYD Kurdish force in Turkey as “terrorists” is unacceptable. In fact, he said that this very same group was causing a “sea of blood” in Syria (BBC, 2016). Erdogan made other harsh comments in an earlier speech, in which he asked the United States, “Are you on our side or the side of the terrorist PYD and PKK organization?” (BBC, 2016). The BBC (2016) reported additional comments by Erdogan, in which he said, ” “Is there a difference between the PKK and the PYD? Is there a difference with the YPG?” he added, referring to the PYD’s militia, the Popular Protection Units. “We have written proof! We tell the Americans: ‘It’s a terror group.’ But the Americans stand up and say: ‘No, we don’t see them as terror groups.'” And, in a CNN (2016), Erdogan also said, “”How will we ever be able trust you?” the Turkish leader said Wednesday about the U.S. government, according to state broadcaster TRT. “Am I your regional partner or are the terrorists in Kobani?””

The United States, while happy with Turkish commitment to the refugees, has disagreed with Turkey’s assessment that the group is a terrorist organization. John Kirby, the United States Department of State spokesperson, said on Monday February 8th, 2016 that they don’t perceive the PYD as a terror group, and are committed to continuing to help them in their fight against ISIS. According to a CNN (2016) report, Kirby said, “”We recognize that the Turks do (label the PYD as terrorists), and I understand that. Even the best of friends aren’t going to agree on everything,” Kirby said. “Kurdish fighters have been some of the most successful in going after Daesh (ISIS) inside Syria. We have provided a measure of support, mostly through the air, and that support will continue.”

Erdogan responded by asking John Bass, the United State ambassador Turkey to be summoned (CNN, 2016).

February 2016 Terror Attack in Turkey

On Wednesday, February 17, 2016, a car bomb went off near a military convey, killing 28 individuals. It was the fourth terror attack in Turkey in recent months (with previous attacks in Istanbul, Ankara, and Suruc). Erdogan immediately suggested that the Kurds were responsible for the attack (Letsch, 2016). According to reports, the attack was committed by a Syrian with ties to the People’s Protection Unit (YPG), a Kurdish force in Syria. According to the Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, he was quoted as saying that ““We collected intelligence all night.”” He went on to say that ““The perpetrators have been fully identified. The attack was carried out by YPG member Salih Necer, who came in from Syria.”” He also stated that the PKK also helped the individual carry out the bombing (Letsch, 2016).

The Turkish government is attempting to use this information to continue to label the YPG a terror organization. He was quoted as saying ““The evidence that shows that the YPG is a terrorist organisation will be given to all countries … Just as we don’t sit down with al-Qaida and Islamic State, we cannot sit down with the YPG either. Those that see Turkey’s enemy as their friend will lose Turkey’s friendship”” (Letsch, 2016). However, the YPG denied any responsibility or connection with Salih Necer (Letsch, 2016).

This seems to be true. Some believe that it is quite possible that the attack was carried out with someone that might have had sympathy for the Kurdish fighters, yet was not given the go-ahead from the organizations to do this (Letsch, 2016). And it seems that this was the case. After the attack, it was reported that a group by the name of the Kurdistan Freedom Falcons took responsibility for the attack. This group is said to be an offshoot group of the Turkish PKK (CBS, 2016).

Turkey responded with military force, as “its jets conducted cross-border raids against Kurdish rebel positions in northern Iraq hours after the attack and struck a group of about 60 to 70 PKK rebels. The Turkish jets attacked PKK positions in northern Iraq’s Haftanin region, hitting the group of rebels which it said included a number of senior PKK leaders, the military said. The claim couldn’t be verified” (CBS, 2016). Then, the day after the car bomb, “six soldiers were killed in southeastern Turkey after PKK rebels detonated a bomb on a road linking the cities of Diyarbakir and Bingol as their military vehicle was passing by, the state-run Anadolu Agency reported” (CBS, 2016).

March 2016 Bombing in Ankara

On March 13th, 2016, a car bomb was detonated in the Turkish capital of Ankara, killing at least 36 people. According to Turkish security forces, the individual carrying out the attack was a member of the Kurdish Worker’s Party (PKK); the Army stated that that the PKK themselves were said to confirm their role in the attack, although this was not initially confirmed. Later reports have suggested that a radical group by the name of the Kurdish Freedom Falcons (TAK) was the one behind the attack (Ozerkan, 2016). According to reports, “In a statement on its website, TAK named the woman bomber as Seher Cagla Demir, who had been involved since 2013 in a “radical fight against a policy of massacre and denial against the Kurdish people.” In addition, it also said that “”On the evening of March 13, a suicide attack was carried out… in Ankara, the heart of the fascist Turkish republic” (Ozerkan, 2016). The group said that that attack was meant to hit government targets, and not civilians (Ozerkan, 2016). However, the group also stated that they were going after Turkey’s tourism sector, saying that “Tourism is one of the important sources feeding the dirty and special war, so it is a major target we aim to destroy…” (Tuysuz, Karimi, & Botelho, 2016).

In response to this attack, “Eleven warplanes carried out air strikes on 18 targets including ammunition dumps and shelters in the Qandil and Gara sectors” (BBC, 2016a). Thus, the violence between the Turkish military and the Kurdish rebels have only intensified in recent months, leaving many to believe that the chance of peace is to be quite unlikely for the time being, given the recent bombings, and the heavy Turkish military actions in the southern part of the country. The Turkish government continues to view the PKK, the TAK, and the YPG (in Syria) as terrorists set on causing havoc in Turkey and Syria. The AKP government is also continuing to further challenge the primarily Kurdish HDP party in Turkey, with Turkish President Ahmet Davutoglu saying that “”If there’s anything worse than the terrorist attacks themselves, it’s the political parties that support them,” which seems to be a direct reference to Kurdish politicians in the government (Ozerkan, 2016).

Thwarted Terror Attacks in Turkey

The terror attacks have continued in Turkey. On April 9th, 2016, it was reported that a percussion bomb went off by a bus stop in the city of Istanbul. This bomb left three people wounded. According to reports, “The blast went off in the busy district of Mecidiyekoy in the European side of the city” (Yahoo, 2016). The explosion was “from a non-lethal stun grenade, designed to create a loud noise and blinding flash” (Al Jazeera, 2016b). As of yet, there is still no official word as to who was responsible for this bomb.

However, it was also reported that on Sunday, April 10th, 2016, “Turkish police have smashed a cell of Kurdish militants in a usually tranquil region between Istanbul and Ankara who had hoarded explosives, guns and suicide vests” (Daily Mail, citing the Dogan News Agency). According to reports, seven individuals from the PKK were arrested, after authorities are investigating an earlier suicide attack. In addition, “The arrests come three days after Bolu police killed two suspected PKK members in an unusual raid in the province which is about half-way between Turkey’s biggest city Istanbul and the capital Ankara, and far from the Kurdish-dominated southeast.”

This comes on the heels of warnings by the United States and Israel that a potential terror attack there were threats of attacks, and that they should be taken seriously (Yahoo, 2016). Israel has called for its citizens to leave the country right away, on account of the activities within Turkey, citing “immediate risks,” and the “US embassy emailed what it called an “emergency message” to Americans, warning of “credible threats” to tourist areas in Istanbul and the resort city of Antalya (Al Jazeera, 2016).

PKK Statements

In late April of 2016, Cemil Bayik, who is one of the original founders of the Kurdish Worker’s Party, said that the PKK was willing and ready to increase their activities against the Turkish state, suggesting that this was due to the government’s actions related to Kurdish areas in southern Turkey. Bayik was quoted as saying “”The Kurds will defend themselves to the end, so long as this is the Turkish approach — of course the PKK will escalate the war” (Varandani, 2016).

May 2016 Fighting

The fighting between the Turkish government and Kurdish forces continued in May of 2016. One noted development in the civil war was the belief that the Kurdish forces had anti-aircraft weaponry, which could shoot town Turkish planes and helicopters. According to reports, On May 14th, 2016, “media affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a leftist militant group battling the Turkish state, posted a video purporting to show a fighter downing a Cobra attack helicopter with a man-portable air-defense system — or MANPADS — in the mountains of southeastern Turkey on Friday morning. Arms observers said this is the first time they have seen PKK fighters successfully using MANPADS in their four-decade fight against the Turks” (Cunningham, 2016). And while the Kurds have used them in the 1997s, the video of the attack happening may be likely to place more attention on the types of weapons that the Kurdish forces have.

Because of this development, there is a concern that this will only magnify the Turkish military’s actions in the southern part of the country (Cunningham, 2016). It may also be a serious concern to the government given the power that such weapons are against tradition state militaries.

In late May of 2016, the Turkish government took off part of the curfew previously implemented in southeastern Turkey; while relaxing the curfew in the morning, an 8pm-5:00am curfew was still in place. They have done this to examine the damage done from the conflict between the Turkish government and the Kurdish forces. According to reports, “Deputy Prime Minister Numan Kurtulmus said Monday that 6,320 buildings have been damaged amid the fighting in five southeastern towns, affecting some 11,000 apartments. He put the estimated cost of demolishing and rebuilding the affected structures__ in the districts of Sur, Silopi, Cizre, Idil and Yuksekova__ at approximately 855 million Turkish lira ($289 million)” (Yahoo News, 2016).

Going into June of 2016, it has been noted that roughly 500 Turkish security has been killed, and 4900 PKK fighters also killed (Yahoo News, 2016).

Removing Immunity

In May of 2016, the Parliament in Turkey voted to remove immunity from elected officials. The reason that many felt the government was doing this was so that they could go after officials from the HDP party, which AKP members view as being tied to the PKK and other Kurdish forces. As reports note, “The new law allows prosecutors to pursue any of the 138 members of parliament who are currently under investigation. Of those, 101 are from the HDP or Turkey’s main opposition party CHP” (Reuters; The Guardian, 2016). For Erdogan and the AKP, this is an attempt to penalize not only those who are Kurdish, but arguably anyone who makes comments against Erdogan and the AKP majority.

While AKP-opposition parties such as the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) backed this bill (which could be used against them as well), the real motivation is to go after the HDP party. Thus, “The overwhelming parliamentary majority that voted in favour of the bill did not leave room for HDP to manoeuvre. Nonetheless, the repercussions of the bill have started to be reflected in the steps and statements of the HDP co-chair, who started to evoke the sympathy of the European Union with an open letter criticising the bill and labelling it as unconstitutional” (al-Burai, 2016).

It is also important to note that the bill was signed by Erdogan in June 7th, 2016, the same day that a car bomb went off in the Beyazit area of Istanbul, killing eleven individuals.

June 2016 Terror Attack in Istanbul

As mentioned above, on June 7th, 2016, a car bomb went off in Istanbul, killing eleven persons, and injuring 36 others. The Kurdish Freedom Falcons took responsibility for this bombing. Not only did they say the carried out the attack, but, according to reports, they also had a message for tourists visiting the country: “”You are not our targets but Turkey is no longer safe for you,” it read. “We have just started the war”” (Time, 2016). The group continued to criticize what they called Erdogan and the AKP’s “wild war” against the Kurds in southern Turkey (Time, 2016). An additional suicide attack followed in the southern city of Midyat.

Erdogan, in response to the June attack in Istanbul, said:

“Let me be clear. Whether the terrorist organization makes any discrimination between police, civilian or soldier doesn’t concern us. At the end of the day, those who becomes martyr is a human. They target humans. And what is the mission of our soldier, police and village guard? It is to provide safety for life and property in this country. Their mission is to ensure the safety of the entire nation. These terrorist attacks target these people who are responsible for ensuring the security. In no way are they forgivable. Therefore, we will continue our fight against these terrorists to the end tirelessly. Our heart is torn apart because we have martyrs. However, there is a price to pay for everything. This struggle, which started with the first human, will continue till doomsday. In no situation can we say we have finished or will finish it. What really matters is to minimize it. To that end, our armed forces, law-enforcement agency and village guards are putting up a collective fight. We will continue to do so, as well” (Presidency of the Republic of Turkey, 2016).

August 2016 Terror Attacks

The terror attacks against the Turkish state have continued into the late summer of 2016. For example, on Friday, August 26th, 2016, “A Kurdish suicide bomber rammed an explosives-laden truck into a checkpoint near a police station Friday in southeast Turkey, killing at least 11 police officers and wounding 78 other people, the prime minister said. The attack struck the checkpoint 50 meters (yards) from a main police station near the town of Cizre, in the mainly-Kurdish Sirnak province that borders Syria. Television footage showed black smoke rising from the mangled truck and the three-story police station gutted from the powerful explosion” (Yahoo News, 2016). It is believed that a group tied to the PKK carried out the attack (Yahoo News, 2016).

The Kurds in Turkey

Along with the outbreak of violence, the Kurds in Turkey have also been upset with how the Turkish government has–in their minds–failed to protect the Kurds in the border towns against the Islamic State forces. This can be seen when looking at the city of Kobane, which is near the Syrian border: “The plight of Kobane, a predominantly Kurdish town right on the border with Turkey, is a lightning rod for many Kurds in Turkey. It’s adjacent to the Turkish town of Suruc, where many residents have direct ties of kinship and clan to those living in Kobane. Last year, as Kobane was besieged by jihadist forces, hundreds of thousands of Syrian Kurdish refugees sought sanctuary across the border. Kurds living in Turkey grew impatient with their government, which they believed was, at best, not doing enough to save Kurdish lives and, at worst, actively colluding with the extremist Islamic State in order to quash Kurdish separatism. That led to days of protests and unrest in October, and triggered violence that claimed some 50 lives” (Tharoor, 2015).

Interestingly, the Kurdish stand at Kobane also helped further advance the notion of Kurdish transnationalism. As GUnes & Lowe: (2015) write:

The successful defence of Kobane was massively significant for Kurds in Syria. The siege created a narrative with potent ingredients: hundreds of thousands of Kurdish refugees fleeing the town; a heroic, 133-day defence of the town by lightly armed Kurdish forces against heavily armed and previously undefeated ISIS troops; the martyrdom of Kurdish fighters, including women; the Turkish state’s refusal to help from across the border; the Kurds on the Turkish side of the border gathering to watch the desperate defence of the town; the arrival of the peshmerga convoy from the KRI with heavier weaponry, celebrating pan-Kurdish fraternity; and then the turning of the tide against ISIS, leading to its expulsion from Kobane. Regardless of the devastation caused, the strategic value of the town or the future progress of the YPG’s battles against ISIS, Kobane will endure as a famous Kurdish victory of huge symbolic value (7).

So, between the state’s response to the Kurds in southeast Turkey, and the recent removal of political immunity, there are concerns by HDP leaders that the Kurdish population will continue to lose trust in the Turkish government (al-Burai, 2016).

In a September 2016 opinion piece in Newsweek, Figen Yüksekdağ, the leader of the HDP party, said that despite the HDPs clear condemnation of the military coup attempt in Turkey, that Erdogan and allies have continued to go after the HDP and Kurds in the country, as well as attacking Kurdish forces fighting the Islamic State in Syria. She said that “None of this had to happen. Had Turkey managed to be at peace with its own Kurds, and ally with the Kurds in Syria, we could be living in a country where blood-thirsty ISIS militants could not roam free. Where over a thousand civilians did not have to die, where bloody coup attempts couldn’t be carried out, where rights and freedoms are not suspended” (Newsweek, 2016). She went on to say that “The government’s deep-rooted, jingoistic hostility for the Kurdish people left them deaf and blind. And they have declared that the PYD, the political representative of Syrian Kurds with thousands of relatives in Turkey, is a terrorist organization. Even though they had hosted its leader in Ankara to cooperate in an endeavor to save its sacred land that was occupied by ISIS.”

September-October 2016

Following the August attacks, and additional attacks on Turkish police, on September 8th, 2016, Turkish leader Erdogan said that Turkey is carrying out one of the largest military actions against the PKK in the history of the country. Along with increasing its military presence in the southeast part of Turkey, the government says that it would take additional steps to fight the PKK, which included the “[removal of] civil servants with links to the PKK” (Al Jazeera, 2016). The government went after thousands of people, which included many teachers they felt were connected to the PKK (Al Jazeera, 2016). According to a report,

The government suspended 11,500 teachers over alleged links to the PKK, an official said on Thursday, after Prime Minister Binali Yildirim said during a visit to the region over the weekend that there were an estimated 14,000 teachers with links to the militants.

Security officials and local media reports said the state had appointed administrators to two municipalities in the southeastern province of Diyarbakir, although the local governor later denied it.

“Reports on the taking over of two mayor’s offices in Diyarbakir do not reflect the truth. There has not been such an appointment at this stage. If there is an appointment, a statement will be made,” the governor’s office said in a statement.

Security officials, the private Dogan news agency, and the state-run Anadolu agency earlier said the government appointed the administrators to replace a pro-Kurdish party because of alleged support for Kurdish militants (Yahoo, 2016).

At the same time, the state continued its crackdown of what it believed were Gulen backers in Turkey (Al Jazeera, 2016).

Furthermore, on September 11th, 2016, the AKP led government dismissed 28 mayors in Kurdish areas of Turkey, accusing them of being tied to terrorist groups. Erdogan was able to do so under a recent law– Decree Law No. 674, which allows the state to go after those involved in terrorism, or backing terror groups (McLaughlin, 2016). Four of the mayors were accused of being connected to the PKK (and 24 to Gulen). A statement from the Interior Ministry said that “”It doesn’t undoubtedly comply with the law for those elected by the public vote to abuse the will of nation to commit crimes against the public,” and went on to say that “The resources created by the taxes honored by our citizens and the political will aroused by their votes cannot be utilized for the benefit of terrorist organizations”” (McLaughlin, 2016).

This led to protests in the Hakkari Province, the Batman Province, and also in the Sanliurfa Province (McLaughlin, 2016). Opposition parties such as the Republican People’s Party and the HDP, as well as the U.S. Embassy were highly critical of these government actions (McLaughlin, 2016).

Then, in October 2016, as Turkey’s war in the southern part of the country continued, reports noted that two bombers carried out a suicide explosion after police went nearer to them. According to reports, “The militants, believed to be a male and female, were suspected of planning to carry out a car bomb attack, the state-run Anadolu news agency reports. They detonated the devices after they were asked to surrender their weapons. Police had been acting on a tip-off, Ankara’s governor said, suggesting a link to Kurdish separatists” (BBC, 2016).

Turkey and the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq

While Turkey is worried about a potential transnational Kurdish independence movement that could greatly influence the Kurds in Turkey, the Turkish government has rather good relations with the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq. The KRG–sitting on significant amounts of oil–has not only built their own pipelines, but they have also started to make their own economic trade deals with countries such as Turkey, to the strong dismay of the government in Baghdad. This also seems to be counter to US interests in Iraq. As Taşpinar & Tol (2014) explain: “Turkey’s growing energy connections with the KRG is another factor that fuels tension between Ankara and Washington. The United States fears that Turkish policies will push Baghdad’s Shi`a government closer toward Tehran and threaten Iraqi unity. In comparison to the situation in 2009, Ankara and Washington seem to have traded places. Now, while Turkey is busy carving up a lucrative space of economic and political influence with Iraqi Kurds, it is Washington that needs to remind Ankara of the importance of Iraq’s territorial integrity” (10). This is a shift for Ankara, which, up until a handful of years ago (around 2009), was rather unwilling to deal with the KRG, and instead, continue to stress the importance of working through the Iraqi leaders in Baghdad (Taşpinar & Tol, 2014).

In late July, 2016, Masoud Barzani, who is the President of the Kurdistan Region called for improved relations between the Kurds in Turkey and the Turkish state, saying that ““Spilling blood between Kurds and Turks must be stopped, because the only correct way is reconciliation and peace.” He also called for unity among the national and Democratic fighting forces in Turkey” (Rudaw, 2016).

Yet, as mentioned above, with heavy casualties on both sides (including a PKK attempt to enter a Turkish military base) (Al Jazeera, 2016a), the fighting between Kurdish and Turkish forces continued throughout summer, and into September (for example, it was reported that on September 12th, 2016, a car bomb detonated in Eastern Turkey, injuring 48).

Kurds in Turkey: The Arrest of the HDP Leaders

In early November 4th, 2016, the head of the HDP party in Turkey, Selahattin Demirtas, Figen Yuksekdag, along with 9 other parliamentary deputies were arrested by Turkish police forces (some of the deputies were later released). According to the Turkish government, “The HDP lawmakers were arrested after they refused to give testimony in a probe linked to “terrorist propaganda” (Reuters, 2016b). However, for the HDP, they feel that they have been unfairly targeted by Erdogan and the AKP for quite some time, and that these actions would not help fight terrorism, but rather, would further risk Turkey spiraling into a civil war. According to reports, “In a video message on a website close to the Kurdish PKK militants, one of the group’s top commanders, Murat Karayilan, said the group would intensify its three-decade-old armed struggle against Turkey and called on Kurds – the country’s largest minority – to react” (Reuters), Shortly after the HDP leaders in Turkey were arrested, a car bomb went off in Diyarbakir, near the police station (and where authorities were holding some of the arrested leaders) (although the Islamic State was said to take responsibility for that bombing) (Reuters, 2016b).

This crackdown on HDP leaders has led to verbal condemnation by western countries. European states leaders, for example, called out what Erdogan and the AKP was doing. For example, “European Union foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini said she was “extremely worried” by the arrests, and raised her concerns in a telephone call with Turkey’s foreign and EU affairs ministers late on Friday. German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier said Ankara had a right to fight terrorism, but could not use it to justify gagging opponents” (Reuters, 2016b).

United States Secretary of State John Kerry said that “The United States is deeply concerned by the Turkish government’s detentions of opposition members of parliament … and by government restrictions on Internet access today”” (Reuters, 2016). At the same time, he told called on the PKK to “cease its senseless brutal attacks” (Reuters, 2016b).

Conclusion

Given the conditions discussed above, there continues to exist a high level of skepticism that any sort of peaceful solution to the Turkey-Kurdish conflict can be reached in the near future. Politically, the government is continuing to lose the Kurdish minority, something that wasn’t always the case in years past. And the violence shows no sign of slowing down. For some, the current climate is much, much worse for the stability and positive future of Turkey. As Cagaptay (2015) writes:

Turkey’s Kurdish problem has changed. Until this year, Turkey’s 10 to 12 million-strong Kurdish community, representing about 15 percent of the Turkish population, wasn’t a unified political force; its internal splits followed the fault lines of the country as a whole. Starting in the 1990s, nationalist Kurds tended to vote for parties sympathetic to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which Turkey and the United States consider a terrorist group, and which fought for decades for independence from the Turkish government. But those voters were not the whole of the Kurdish electorate. Since the 1960s, the left-leaning Alevi Kurds, who adhere to a liberal branch of Islam, have voted for the social-democratic Republican People’s Party, which is a secular, Turkish-nationalist movement. More importantly, conservative Kurds, who by my estimate represent nearly half of the Kurdish population, have tended to vote for the governing, pro-Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP) ever since it was established by former prime minister, and current president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in 2001.

However, as we have discussed, things have changed. The HDP is winning Kurdish voters, the gains by Kurdish forces in Syria are helping the movement in Turkey, and the government crackdown on Kurdish cities is infuriating the Kurdish minority. As Cagaptay (2015) argues, because of these developments (and a heavy and oppressive) government hand, “Previously when the government fought the PKK, it could count on help from the local Kurdish population. That is no longer the case.”

Plus, it is evident that the Turkish government under Erdogan has no interest to sit down and negotiate with the PKK. It has been noted that “Erdogan has said the state would “bring the whole world down” on those who seek autonomy, and that from now on, neither the PKK nor any related political party would be accepted as a negotiating partner. “That affair is over,” he told a group of village heads visiting his presidential palace” (Lepeska, 2016). This has also put outside actors in difficult positions. For example, Europe views Ankara as a strong ally, and so they don’t want to jeopardize that relationship. However, the “[t]he YPG, on the other hand, has proven to be an effective “boots- on-the-ground” partner and complement to the anti-IS coalition’s airstrikes in northern Syria, albeit in predominantly Kurdish areas” (Salih, 2015). Thus, it seems that, as of now, that the two sides are strongly opposed to one another, and the outside actors will be unable (or unwilling) to help settle the dispute.

The likelihood of peace is further questioned following the attempted military coup in Turkey.

References

Abramowitz, M. (1998), Foreword, in Turkey’s Kurdish Question, Barkey, H. & Fuller, G. New York, New York. Roman & Littlefield.

Al-Burai, A. (2016). What’s behind Turkey’s bill of immunity. Al Jazeera. 29 May 2016. Available Online: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2016/05/turkey-bill-immunity-160529083635081.html

Al Jazeera (2016): Turkey conducting ‘largest ever’ operations against PKK. Al Jazeera. September 9th, 2016. Available Online: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/09/turkey-conducting-largest-operations-pkk-160909054349070.html

Al Jazeera (2016). Turkey: PKK fighters killed in attempt to storm base. Al Jazeera. July 30, 2016. Available Online: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/07/turkey-pkk-fighters-killed-attempt-storm-base-160730082403245.html

Al Jazeera (2016). Turkey: US and Israel warn of ‘imminent’ attack threat. April 10th, 2016. Available Online: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/04/israel-warns-concrete-attack-threat-turkey-160409064901474.html

Amnesty International (2016). Turkey. Displaced and Dispossessed. Amnesty International. Available Online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2016/12/sur-displaced-and-dispossessed/

BBC (2016a). Ankara bombing: Turkey strikes against Kurdish rebel PKK. BBC. March 14th, 2016. Available Online; http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35799998

BBC (2016). Turkey’s Erdogan denounces US support for Syrian Kurds. BBC. February 10th, 2016. Available Online: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-35541003

BBC (2016). Turkey suicide bombers killed near Ankara after police ‘tip off’. BBC News. October 8, 2016. Available Online: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-37594948

Benli, M.H. (2016). Turkish academic faces jail for the ‘terror propaganda’ over exam question on PKK leader. Hurriyet Daily News, February 2nd, 2016. Available Online: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/Default.aspx?pageID=238&nID=94648&NewsCatID=339

Cagaptay, S. (2015). Turkey is in Serious Trouble. The Atlantic. October 5th, 2015. Available Online: http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/10/turkey-isis-russia-pkk/408988/

CBS (2016). The Kurdistan Freedom Falcons claims responsibility for terror attack in Ankara, Turkey. CBS News. February 19, 2016. Available Online: http://www.cbsnews.com/news/kurdistan-freedom-falcons-claims-responsibility-for-terror-suicide-bomb-attack-in-ankara-turkey/

Charlotte Observer (2016). 48 injured by PKK car bomb in east Turkey. The Charlotte Observer. In Yahoo News. September 12, 2016. Available Online: https://www.yahoo.com/news/m/e850eef9-5c87-34dd-808a-f1dddbc51986/ss_48-injured-by-pkk-car-bomb-in.html

CNN (2016). Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan slams U.S. on Kurd support. February 10, 2016. Available Online: http://www.cnn.com/2016/02/10/middleeast/turkey-erdogan-criticizes-us/index.html

Committee to Protect Journalists (2015). “Turkey press crackdown continues with arrests of three pro-Kurdish journalists.” 22nd December, 2015. Available Online: https://cpj.org/2015/12/turkey-press-crackdown-continues-with-arrests-of-t.php

Cunningham, E. (2016). Kurdish militants reportedly shoot down Turkish security forces helicopter. The Washington Post. May 14, 2016. Available Online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/05/14/kurdish-militants-just-challenged-turkish-air-power-in-a-major-way/

Daily Mail (2016). Turkey breaks Kurdish militant cell ‘preparing attack’: report. 10 April 2016. Available Online: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/afp/article-3532750/Turkey-breaks-Kurdish-militant-cell-preparing-attack-report.html

Henley, J., Shaheen, K., & Letsch, C. (2015). Turkey Election: Erdoğan and AKP return to power with outright majority. The Guardian. Monday 2 November 2015. Available Online: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/nov/01/turkish-election-akp-set-for-majority-with-90-of-vote-counted

Lepeska (2016). Kurds in Turkey: Caught in the Crossfire. Al Jazeera, 31 January 2016. Available Online: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2016/01/kurds-turkey-caught-crossfire-160131073950258.html

Letsch, C. (2016). Turkey says Kurds in Syria responsible for Ankara car bomb. The Guardian. Thursday February 18, 2016. Available Online; http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/feb/18/explosion-hits-another-turkish-military-convoy-one-day-after-ankara-attack

McLaughlin, E.C. (2016). Turkey replaces 28 mayors, sparking outcry, protests. CNN. September 11, 2016. Available Online: http://www.cnn.com/2016/09/11/europe/turkey-mayors-replaced-erdogan-crackdown-protests/

Newsweek (2016). We Are Trying to Prevent Further Chaos in Turkey. Newsweek. September 15, 2016. Available Online: http://europe.newsweek.com/we-are-trying-prevent-further-chaos-turkey-498819

Ozerkan, F. (2016). Kurdish group close to PKK claims deadly Ankara attack. Yahoo News. March 17th, 2016. Available Online: http://news.yahoo.com/radical-kurdish-group-close-pkk-claims-deadly-ankara-080118522.html?nf=1

Presidency Of The Republic of Turkey (2016). President Erdogan Visits Blast Victims in Istanbul. 7.06.2016. Available Online: http://www.tccb.gov.tr/en/news/542/44302/cumhurbaskani-erdogan-istanbulda-teror-saldirisinda-yaralananlari-ziyaret-etti.html

Rosenfeld, J. (2016). Turkey Is Fighting a Dirty War Against Its Own Kurdish Population. The Nation. March 9, 2016. Available Online: http://www.thenation.com/article/turkey-is-fighting-a-dirty-war-against-its-own-kurdish-population/

Reuters (2016). Erdogan lifts Turkish MPs immunity in bid to kick out pro-Kurdish parties. Reuters; The Guardian. June 7, 2016. Available Online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/08/erdogan-lifts-turkish-mps-immunity-in-bid-to-kick-out-pro-kurdish-parties

Reuters (2016b). Turkey draws Western condemnation over arrest of Kurdish lawmakers. Reuters. Friday November 4, 2016. Available Online: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-turkey-security-kurds-idUSKBN12Y2XA

Reuters (2016). Turkey suspends thousands of teachers, wages ‘biggest campaign’ against Kurds. Reuters. In Yahoo News. September 8th, 2016. Available Online: https://www.yahoo.com/news/turkey-takes-over-councils-suspends-teachers-over-kurdish-140711114.html

Rudaw (2016). Barzani urges Turks and Kurds in Turkey to reconcile. Rudaw, July 28, 2016. Available Online: https://www.yahoo.com/news/toll-rises-8-dead-deadliest-pkk-attack-since-083957540.html

Salih, C. (2015). Turkey, the Kurds, and the Fight Against the Islamic State. European Council on Foreign Relations Brief. September 2015. Available Online: http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/Turkey-the-Kurds-Islamic-State2.pdf

Solaker, G. & Dikmen, Y. (2016). Several lawmakers were hurt when a fight broke out on Turkey’s parliament. Business Insider, May 2nd, 2016. From Reuters. Available Online: http://www.businessinsider.com/several-lawmakers-were-hurt-when-a-fight-broke-out-in-turkeys-parliament-2016-5

Taşpinar, O. & Tol, G. (2014). Turkey and the Kurds: From Predicament to Opportunity. Center on the United States and Europe: Brookings Institute. US-Europe Analysis Series Number 54, January 22, 2014. Available Online: http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2014/01/23-turkey-kurds-predicament-opportunity-taspinar-tol/turkey-and-the-kurds_predicament-to-opportunity.pdf

Tharoor, I. (2015). Why many Kurds in Turkey are willing to die in Syria’s border towns. Washington Post, June 26, 2015. Available Online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/06/26/why-many-kurds-in-turkey-are-willing-to-die-in-syrias-border-towns/?tid=a_inl

Tharoor, I. (2016). As Syria burns, Turkey’s Kurdish problem is getting worse. Washington Post, February 3rd, 2016. Available Online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/02/03/as-syria-burns-turkeys-kurdish-problem-is-getting-worse/

Time (2016). Kurdish Group Warns Tourists That Turkey Is No Longer Safe. Time Magazine. In Yahoo News. June 10, 2016. Available Online: https://www.yahoo.com/news/kurdish-group-warns-tourists-turkey-091447577.html

Tuysuz, G., Karimi, F., & Botelho, G. (2016). Istanbul explosion: Suicide bomber had ISIS links, says Turkey’s interior minister. CNN. March 20, 2016. Available Online: http://www.cnn.com/2016/03/19/europe/turkey-blast/index.html

Uras, U. (2015). HDP: Party of Turkey’s Oppressed? Al Jazeera, 29 October 2015. Available Online: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/10/hdp-party-turkey-oppressed-151029090141649.html

Varandani, S. (2016). Kurdish PKK Ready to Intensify Fight Against Turkey, Leader Blames Erdogan for ‘Escalating This War.’ International Business Times, April 25, 2016. Available Online: http://www.ibtimes.com/kurdish-pkk-ready-intensify-fight-against-turkey-leader-blames-erdogan-escalating-war-2358933

Yahoo (2016). Kurdish militants claim deadly car bomb attack in Turkey. Yahoo News. August 26, 2016. Available Online: https://www.yahoo.com/news/several-reported-wounded-turkey-car-bomb-attack-054959606.html

Yahoo (2016). Three wounded in Istanbul blast: report. April 9, 2016. Available Online: https://www.yahoo.com/news/three-wounded-istanbul-blast-report-202904786.html

Yahoo News (2016). Turkey rolls back curfew in Kurdish area, assesses damage. Yahoo News. May 30, 2016. Available Online: https://www.yahoo.com/news/turkish-authorities-partially-lift-curfew-kurdish-areas-090553953.html?nhp=1