Israel Palestine Conflict

This article will go into the detailed history with regards to the Israel Palestine conflict. It will discuss major historical events, key actors, noted events, the various arguments regarding the different sides, as well as current issues in the Israeli Palestine Conflict. In the article, we will also answer frequently asked questions with regards to the Israel Palestine Conflict. This article will show that despite the argument that some make regarding ethnic tensions between Jews and Arabs, or historic religious tensions between Jews and Muslims, the Israel Palestine conflict actually has very little to do with religion. Instead, “[t]he ongoing battle between the Israelis and Palestinians is rooted in a struggle between two peoples over land, national identity, political power and the politics of self-determination” (Milton-Edwards, 2009: 9). This conflict continues to be one of the most discussed in the Middle East, and arguably in the greater field of international relations.

History of the Israel Palestine Conflict

The history of the Israel Palestine conflict has its roots in the events of the mid 1800s and and the early 1900s. There were a number of issues that need to be addressed, in order to see how the Israel Palestine conflict came about. In this section, we shall discuss political Zionism, the actions of Britain in the Middle East during World War I, and the tensions that followed in Palestine. As Cleveland & Bunton (2013) argue, in order to understand the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in detail, it becomes necessary “to examine the interactions among the British, the Zionists, and the Palestinian Arabs in order to illustrate the main issues of the mandate era” (221), and from that, how those events led to additional tension between the different actors.

The Ottoman Rule in Palestine

But while political Zionist leaders were advocating a Jewish homeland away from the discrimination of Europe, in the Middle East, the Ottoman Empire was in control of Palestine. Scholars argue that in the 1800s, they began to take a much greater interest in the region, and in Jerusalem specifically. Part of this had to do with the rise of Muhammad Ali’s power in Egypt; as he seemed to build up his power, and even before his control of Syria, the Ottomans tried to counter this by shoring up their own power in Palestine (Abu-Manneh, 2007). The Ottoman Empire had control of Palestine until the early 1900s, and in their control, governed the area in three separate sanjaks or units: Jerusalem, Nablus, as well as Acre.

However, before World War I, these territories were included in different government structures; Nablas and Acre went into the political governance of Beirut, and the Jerusalem sanjak was on its own. However, it was the various territories in the area, namely the land west of the Jordan River, and the area that was south of Beirut area was called Palestine; despite arguments by some Palestine did not exist, there is ample evidence that many were in fact calling the area “Palestine” (Harms & Ferry, 2005: 58). And it was at this time during the First World War that Palestinians began more directly establishing a common national identity.

As Harms & Ferry (2005), explain, “Nationalism as a way of thinking deepened over time as a result of the culture’s evolution, in particular, the development of the region’s trade and commerce, and its subsequent engagement with Western European markets” (59). They go on to explain that “Palestinian Arabs began to look further than their villages and farms, and started to think and feel collectively. As the years progressed toward World War I the developing Palestinian identity was met with increasing changes in landholding patterns, an issue that lay at the very center of that identity” (59).

Political Zionism

While many point to the first decade of the 1900s to help explain the foundations of the Israel Palestine Conflict, to get a fuller picture, one must begin by looking at the conditions facing the Jewish community in Eastern and Western Europe. Historically, many Jews who lived in Palestine were forced to flee following Rome’s conquering of the territory in the first century after the common era. And while they did not have access to this territory, “Palestine occupied so central a place in Jewish religious culture because of the belief that the establishment of the Kingdom of Israel after the Exodus represented the fulfillment of God’s promise to the Jews that they were chosen to complete their destiny in Zion” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012).

This reflection on returning to Palestine was important to many Jews throughout the centuries. However, as Cleveland & Bunton (2012) argue, it was the events in the 1800s that led to the rise of Political Zionism, in which aspects of this movement called for the return to Palestine. Along with this belief by some in the Jewish diaspora that the Jewish community would return to Palestine, there was also a history of discrimination against Jews living throughout Western Eastern Europe. Jews throughout Europe were often unable to enter into any profession of their choosing, were barred from levels of higher institution, and they were often not allowed to work in the government. Moreover, they were also often forced to live in certain areas (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012).

And while some argue that the situation for Jews was improving in Western Europe, things were still highly repressive in Eastern Europe. For example, the political regimes of Alexander III, as well as Nicholas II in Russia continued to carry out violations of human rights against the Jewish communities in these states. As a result, some individuals from the Jewish community began looking into the idea of a Jewish homeland away from the discrimination in Europe. Many of the early political Zionist leaders such as Leo Pinsker felt that Jews would not be seen as equal citizens in these countries, even if the law said so. And thus, it was critical for Jews to have a place of their own whether they could practice their faith and live freely (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012).

Other Zionist thinkers such as Theodor Herzl also advocated the idea of a state for Jews, saying that the Jewish community were a nation without a state where they could live without discrimination (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012). This work not only noted a political goal, but Herzl began brining different Zionist groups under one umbrella. One of the first large-scale events of various Zionist groups was the 1897 Zionist Congress held in Basel (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012). Looking at Herzl’s work, as well as those in attendance at the 1897 Zionist Congress, it was evident that many within the political Zionist movement in the early 1800s were actually not focused on religious arguments for a Jewish state, but rather political ones. In fact, some of the early Zionists were actually open to a Jewish state in various parts of the world; Palestine, to a number of them, was not a necessary homeland for the Jews. As we shall see, the Zionist movement did differ on this issue as to whether the future Jewish state would need to be in Palestine or if it was acceptable to be elsewhere.

However, it was at the 1897 Zionist Congress that the idea of future homeland for the Jews in Palestine was solidified. This conference “…attracted over 200 delegates and represented a millstone for the Zionist movement. The congress adopted a program that stated that the objective of Zionism was to secure a legally recognized home in Palestine for the Jewish people. Equally important, the Basel congress agreed to establish the World Zionist Organization as the central administrative organ of the Zionist movement and to set up a structure of committees to give it cohesion and direction” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 224). This then led to additional branches in other parts of Eastern Europe (224).

Palestine During the Ottoman Empire

Palestine and Israel (prior to the creation of the state of Israel) were governed under the Ottoman Empire, although they were not administered as a unified territory. For example, “The northern districts of Acre and Nablus were part of the province of Beirut. The district of Jerusalem was under the direct authority of the Ottoman capital of Istanbul because of the international significance of the cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem as religious centers for Muslims, Christians and Jews” (Beinin & Hajjar, 2014: 2). As we shall see, the weakening of the Ottoman Empire in the late 1800s and early 1900s, as well as the rise of the British Empire (and their increased interests in the Middle East) led to a series of events that dramatically altered the political and territorial conditions of the region understood as Palestine.

Palestine and World War I

While many often like to look toward either recent events, or very early events (such as those before the common era) in their attempts to find the origins of the Israel Palestine conflict, much of the conflict can be traced back to the actions of World War I. During this time period, there were a few things that occurred that have shaped the situation, bringing about conflict between various actors.

In order to understand the Israel Palestine conflict, it is important to analyze the events and interests behind various events that transpired during this time period. In fact, many scholars argue that the Israel Palestine conflict can be traced to the World War I years. There were number of events and factors during this time period that led to conflict between the Zionists and the Palestinians in Palestine. During World War I, Germany was fighting against the Allied powers of Britain, France, and Russia. The Ottoman Empire, at the time, had not yet made a decision in regards to who they were going to back.

However, there were different reasons that the Ottoman Empire decided to side with Germany. One of the key reasons was due to the capitulation agreements that they had made with Britain and France. Initially, agreements to protect British and French nationals working the Ottoman Empire, as Britain and France rose in power, they continued to rewrite these agreements, more and more in their favor. Furthermore, Ottoman Empire was indebted to many of these outside states, and thus, siding with Germany, and hoping for a victory, would help alter the relationship that they had with these European powers.

Moreover, the German leadership continued to attempt to appeal to the Ottoman Empire to align with them, and made various references to Islam, hoping to sway the Islamic empire (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012). Britain and France, seeing that the Ottomans ended up siding with Germany, were looking to respond to their action. To begin, it was believed that they thought they would still come out victorious in the war. Thinking this, Britain and its allies began drawing up plans to divide the Ottoman Empire territory. They did this through the Sykes-Picot Agreement. In this agreement, Britain would control parts of Arabia, Iraq, Kuwait, and Transjordan, and France would have control or influence over much of Lebanon, Syria, and parts of Turkey. Palestine would be an international zone, governed directly by neither Britain nor France, although Britain did take a major role in administering the area.

Sykes-Picot Agreement 1916. Reproduced from http://www.passia.org with permission, Ian Pitchford, (Mahmoud Abu Rumieleh, Webmaster) 15 April 2006

However, in the meantime, Britain was also concerned about what the Ottoman alliance with Germany would do for the rest of the Muslims in the world. Namely, there were some in Britain that believed that the Ottomans going with Germany would mobilize the rest of the world’s Muslim community. Thus, British leaders thought that to help prevent this, they would have to find a Muslim ally to work with them. The individual that they began speaking with was the Husayn Ibn Ali, who was the Amir of Mecca. He had the task of overseeing Islam’s holy spaces in Mecca.

Thus, British representative Sir Henry McMahon had a dialogue with Husayn about a possible alliance following Husayn’s correspondence. But, the Committee for Union and Progress, in the Ottoman Empire, also wanted him to join on their side of the war. Cleveland and Bunton (2012) explain that “[t]he CUP government, as wary of Husayn as he was of them, endeavored to persuade him to declare his support for the caliph’s jihad and to commit contingents of his tribal levies to the Ottoman war effort. The sharif hedged. He did so because he was in the midst of deciding whether his personal ambitions could best be served by supporting Ottomanism or by pursuing other alternatives” (145). Husayn and McMahon began exchanging communications with regards to what the conditions of such a partnership would look like. These ten letters are referred to as the Husayn-McMahon correspondence, which took place between July 1915 and March 1916 (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 145). In terms of this relationship

Britain was receptive to the idea of an Arab rebellion against the Ottomans as well as the opportunity of acquiring a Muslim ally Husayn’s distinction; McMahon was instructed to follow up on Husayn’s initiative. The thorniest issue in their correspondence concerned frontiers. Husayn, claiming to represent all the Arab people, requested British recognition of an independent Arab state embracing the Arabian Peninsula, the provinces of Greater Syria (including Lebanon and Palestine), and the provinces of Iraq–essentially the Arabic-speaking world east of Egypt–in exchange for this commitment to lead an armed rebellion against the Ottomans” (145).

Britain, while in favor of an ally, disagreed with including the territory west of Damascus, Homas, Allepo, as well as Hama, mainly because France already had an interest in this territory (see the Sykes-Pictot agreement discussion above). However, this was a point of disagreement between Husayn and Britain. They left to agree to this later, following the war. Another point of contention was Iraq. Husayn saw Iraq as part of his post-war state, and Britain wanted to control Baghdad, as well as Basra. Husayn did say that Britain could have a presence in the area until local administration was established (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012). But it was this agreement that was a key event that has led to tensions with regards to the Israel Palestine conflict. The issue was that so much of the territory was not yet agreed upon, and that “McMahon’s language was so ambiguous and so vague that it has given rise to widely conflicting interpretations over whether Palestine was included as part of the future independent Arab state” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 148). Speaking on this issue, Cleveland & Bunton (2012) say that

“Palestine was not specifically mentioned in the correspondence, but British officials later claimed that the region was part of the coastal Syrian territory that had been reserved for France and was thus excluded from the Arab state, even though it lay south of the Damasca-Aleppo line McMahon mentioned. However, this argument had its flaws. Because Palestine was indeed located south of Damascus, proponents of the Arab claim to the region argued that it could not possibly have been part of the territory lying west of the Damascus-Aleppo line that that is must therefore have been included in the Arab state promised to Husayn. It is likely that at the time of his negotiations with Husayn, McMahon did not pay much attention to Palestine as a distinct region and probably intended it to be part of the Arab state” (148).

The Balfour Declaration

Thus, it seems that Britain promised Palestine to Husayn as part of the Husayn-McMahon correspondence, in exchange for his help fighting the Ottomans in Palestine. Yet, at the same time that Britain was promising territory to Husayn for an Arab-state following the war, they were also making deals with France and Russia over territory in the Middle East. But that was not all. Not only did Britain promise Palestine to Husayn, but they also supported the idea of a national homeland for the Jewish diaspora in Palestine. Britain promised the area to the Jews and Arabs. In November of 1917, in a letter from Author Balfour to Lord Walter Rothschild, which is known as the Balfour Declaration, this declaration called for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. The text reads:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done with may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country” (in Caplan, 2010: 58).”

Thus, by stating this position in the Balfour Declaration, Britain satisfied many of the Zionists who were hoping for such a position by Britain. However, as we shall discuss later, many Palestinians and Arabs in the region were furious at this announcement, both because of its lack of reference to Palestinians or Arabs directly, and because it seems that this completely went against the promises in the Husayn-McMahon correspondence (Caplan, 2010). There were a number of reasons as to why Britain passed this letter calling for a home for the Jewish people in Palestine. As Caplan (2010), explains, “[a] mixture of imperial realpolitik and religious sentiment combined to help members of the Cabinet respond sympathetically to sustained lobbying efforts by Zionist leaders. Hard-headed political considerations included hopes of gaining international Jewish support for the British war effort and post-war interests (58).

A number of British leaders believed “that Jewish groups in the United States and Russia had the capacity to influence their respective governments’ attitudes toward the war. Until the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, the British cabinet was worried that Germany might make a declaration in support of Zionist aims and thus attract a sympathetic response from US jewry. A similar consideration arose with regard to Russia, which was on the verge of military collapse and social revolution by autumn 1917. Officials within the British government argued that a British gesture of goodwill toward Zionist aspirations might persuade influential Jewish members within the revolutionary movement to attempt to keep Russia in the war” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 225).

Regardless of how true and possible these beliefs were, it nonetheless drove a number of British officials to take this position (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012). In addition to war interests, Britain also had other political interests in Palestine. Namley, they saw a role for themselves in Palestine. They had a number of interests in the region, including but not limited to Egypt and Iraq. Having say over Palestine would allow them to have more secure access tot he Suez Canal, a critical waterway that Britain used with regards to their control over India. Moreover, in a struggle against other colonialist states such as France, controlling Palestine would prevent France from having a presence in the region (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012).

Along with the geopolitical interests in the region and with regards to World War I, “[t]hese [interests] were combined with the religious beliefs of several influential British statesmen whose reading of the Biblical prophecy made them sympathetic to the aspirations of the scattered Jewish people to return to live in the land of their ancestors” (Caplan, 2010: 58). Moreover, it is also important to also look at the Zionist movement in Britain. One of the key Zionist figures, Chaim Weizmann, continued to press for the issue of Zionism among the members of the British government. Scholars argue that “…[Weizmann] was effective in keeping the question of Zionism before the British support for Zionism and in cultivating ties with well-placed officials and public figures. He was helped immensely in his task by the cabinet’s recognition that British support for Zionism had the potential to serve British imperial interests” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 225). Thus, Britian’s fracturing relationship with the Amir of Mecca, the belief that the Jewish diaspora could influence the Russian government, the role of Weizmann in Britain, and Britain’s hope that they could be active in Palestine (all the while limiting French interest in the area) were the reasons why they stated their position for a Jewish homeland in the Balfour Declaration.

Israel Palestine Conflict: Post World War I

Having promised Palestine to both Husayn, as well as the Zionists, Britain, through the Reno Conference of 1920, had a mandate in Palestine (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012). And now had a lead role in attempting to oversee what would be a complicated situation. And it seems that they were trying to find a way to carry forward the commitment to the Zionists, as well as the protections to the Palestinians. For example, in attempts to ensure the Zionists and the Palestinians would both be happy, the British government attempted to establish dialogues with both leaderships from 1917 (when they took over Jerusalem) until 1920. For example, “In an agreement reached in January 1919, Weizmann pledged that the Jewish community would cooperate with the Arabs in the economic development of Palestine. In return, Faysal would recognize the Balfour Declaration and consent to Jewish immigration” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2013: 226). What is important to note here is that “Faysal did not, as some have claimed, agree to the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. When the French occupied Syria, the provisions of the Faysal-Weizmann agreement were violated and the document was rendered void” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2013: 226).

But despite their attempts at reconciling the different groups, the British government was (and has been) criticized for their actions regarding Palestine following the end of World War I. One of the controversial decisions was Britain’s “appointment of Sir Henry Samuel as civilian high commissioner in 1920” (228). This upset the Palestinians because Samuel was himself a Zionist (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012). Not only that, but prior to the selection of Samuel, the League of Nations (a then new international organization created to ensure international security) not only backed the new mandate in Palestine, but they also supported the Balfour Declaration, and also included Hebrew as one of the official languages within Palestine (Cleveland & Bunton, 2013: 226).

Due to agreements during and following World War I, in 1921, Britain established the state of Transjordan, and then the Palestinian Mandate, which was loosely governed by Britain. This development further upset the local Arab population, in particular, because they were promised a unified state that they believed would have included Palestine, the Hijaz, as well as Syria. However, not only did Britain not provide this state, but the increase in influence by Samuels (and other Zionist leaders), as well as a rise in the Jewish immigration into Palestine concerned many of the Palestinians (Beinin & Hajjar, 2014), who felt that their political voice and interests were not being recognized. Thus, there were a number of conflicts between Arabs and Jews over land, politics, etc… These tensions were heightened when groups such as the Jewish National Fund “purchased large tracts of land from absentee Arab landowners, the Arabs living in these areas were evicted. These displacements led to increasing tensions and violent confrontations between Jewish settlers and Arab peasant tenants” (Beinin & Hajjar, 2014: 2).

Britain, during this entire time period, and in the years following, found itself in a very difficult position. They clearly had a hostile situation on the ground, and one that they were having increased difficulty in trying to control. On the one hand, it had made promises to the Jewish diaspora, and was trying to find ways to allow the migration into Palestine to occur without issues. In addition, many in the government were supportive of the Zionist movement because it seemed to align with their own interests (of being able to justify still having a presence) in Palestine (Harms & Ferry, 2005). On the other hand, much of this migration impacted local politics and economics, and many Palestinians were quiet upset with these developments, and thus, Britain aimed to appease the local population as well.

Plus, it is important to note, that it did seem to be Britain’s position that Palestine would be a Jewish state. They seemed to believe that a Jewish homeland could be established, all the while making sure that the Palestinian rights would be secured (Cleveland & Bunton, 2013). They even tried to state this position clearly in a 1922 White Paper in which they attempted to support both the Jewish right in Palestine, and also the rights of the Palestinian Arabs. However, not only did this document not help clarify matters (Cleveland & Bunton, 2013), but as we shall see, many felt otherwise about the possibility of both being secured equally without any hostility or disagreement.

With regards to the Jewish homeland, the establishment of the Balfour Declaration led to Jewish immigration in Palestine. In fact, there were various periods–or aliyahs–of Jewish immigration in the years before and then following World War I. With regards to the aliyahs following the war, “[t]he third, from 1919 to 1923, was composed of about 30,000 immigrants mainly from Eastern Europe. An additional 50,000 immigrants, primarily from Poland, arrived in the fourth aliyah between 1924 and 1926” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 235). Then, the next aliyah occurred in the early 1930s following the rise to power of Hitler and the Nazis in Germany (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012). It was the increase in population in the region that made economic and political issues more contentious. Along with the rise of Jewish immigration, there was also a growth of the Arab population from 700,000 to 983,000 people. All of this led to an increase in 500,000 people in a very short time period, which in turn causes tensions with regards to access to farming land (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012). In an attempt to clarify their position on Palestine, in 1922, Britain published a white paper. Here, they tried to clarify their position on Palestine, but many argue that it did far from resolve the Israel Palestine conflict as we refer to it today.

As alluded to above, one of the most discussed historical points of the time period is with regards to the purchasing of land. At the time, “The Zionist organization chiefly responsible for negotiating land purchases was the Jewish National Fund, which bought land it then regarded as belonging to the Jewish people as a whole and leased it exclusively to Jews at a nominal rate. The Jewish National Fund also provided capital for improvements and equipment, a practice that enabled impoverished immigrants to engage in agricultural pursuits immediately upon arriving in Palestine” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 236). Many of these Zionist organizations bought the land from Arab landowners that were no longer in Palestine. Or, some of the local Arab families that owned high percentages of land sold them to the Zionists for what was at the time high economic prices. Thus, “[b]y 1939, some 5 percent of the total land area of the mandate, making up approximately 10 percent of the total cultivable land, was Jewish-owned” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 236). This land transfer affected many of the Palestinians. With thousands of them working these lands, after the transfer, many were out of jobs. Thus, the economic situation was worsening for them. And for other Palestinian farmers, “The conditions of small proprietors also worsened during the mandate. British taxation policy, which required direct cash payments in place of the customary Ottoman payment in kind, forced peasant farmers to borrow funds of high rates of interest from local moneylenders–who were frequently the large landholders. As a result of the crushing burden of indebtedness, many small proprietors found it necessary to sell their lands, sometimes to Zionist interests but often to one of the landed Arab families” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 236). These factors combined upset many within the Palestinian population.

Along with these land issues, there were also social tensions within Palestine. In 1928 and 1929, for example, the Wailing Wall Disturbances occurred. Here, before Britain took control of Palestine, the position on the Wailing Wall–which is a religious site for Jews, as well as Muslims (as within the wall is the Dome of the Rock, as well as Al Aqsa Mosque) was one in which the Palestinians controlled the religious sites, but Jews of course could visit. One of the rules that Britain kept in place was that any form of gender separations (such as benches, etc…) were not permissible. In 1928, after attempts to challenge this position, Britain moved one of the screens. This upset some in the Jewish community. In turn, the Muslim mufi (or leader) in Jerusalem spoke out not only of the placing of the screen, but in his mind, what he also saw the Zionist threat to the Dome of the Rock and Al Aqsa Mosque. Various voices were contesting the rights to the wall, and in 1929, violence broke out on August 15th, 1929, after “members of the Betar Jewish youth movement (a pre-state organiza- tion of the Revisionist Zionists) demonstrated and raised a Zionist flag over the Western Wall.

Fearing that the Noble Sanctuary was in danger, Arabs responded by attacking Jews in Jerusalem, Hebron and Safed” (Beinin & Hajjar, 2014: 3). Cleveland & Bunton (2012) explain that “in August 1929, during which Arab mobs, provoked by Jewish demonstrations, attacked two Jewish quarters in Jerusalem and killed Jews in the towns of Hebron and Safad. By the time British forces quelled the riots, 133 Jews and 116 Arabs had lost their lives” (237).

Britain also tried to find a longer term solution to what was happening. They established a Peel Commission in the mid 1930s (they passed a repot in 1937) to look into what was happening in the country. Among other things, the Peel commission did point out the difficulties of a single state built based on promises offered through the Balfour Declaration would not be possible. As a result, the Peel Commission recommended two separate states. Both groups were upset with this recommendation. The Arab leadership felt that this took away Arab rights to the land, and to many of the Zionist leadership, they accepted the idea of separate areas, but were not happy with the amount of land they would receive (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012). As a result of these rising tensions, Palestinian Arabs began to strike. Others began to carry out rebellions. Here, they went after British installations, as well as attacking Jews and Jewish property in Palestine (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 240). As a result, Britain increased their troop presence in Palestine.

Prior to the Second World War, and because of the racist policies and actions of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Germany, the number of Jews–who no longer felt safe in Germany and other parts of Europe–immigrating to Israel rose. With the arrival of more people led to an increased need for land to accommodate these individuals. However, the Arab populations viewed the additional Jewish settlements as something that would continue to weaken their control over Palestine. In 1936-1939, an Arab Revolt broke out in Palestine. Following the suppression of this revolt in 1939, Britain published a 1939 White Paper in which they gave the Arabs the hope of a future majority state within the decade, while also placing a limitation on immigration (Beinin & Hajjar, 2014).

World War II and the Israel Palestine Conflict

As mentioned, in 1939, Britain, trying to resolve the conflict in Palestine, published another White Paper. This White Paper of 1939 went against the idea of Palestine being a Jewish state. In addition, it called for capping Jewish immigration to Palestine, and then, after five years, would be halted. They also called for limited land transfers to the Jewish community to only certain areas, and that, following a ten year period, Palestine would no longer be under British control, but would become independent.

This latest announcement infuriated the Jews, who felt that Britain was turning back from their promises within the 1917 Balfour Declaration. Thus, the Zionist movement moved away from an alliance with Britain, urging supporters to challenge the new policies. During this time, the Palestinians, while many of them were happy with the statements within the 1939 White Paper, they were not able to have a unified political block, given not only their defeat in the revolt, but also that their leadership was exiled (Beinin & Hajjar, 2014). Given the developments in Europe, and the increase Jewish refugees leaving Germany and other countries, they were very upset with the plan and the limitations that the White Paper outlined. It led individuals such as Ben-Gurion to say: “We shall fight with Great Britain in this war as if here was no White Paper, and we shall fight the White Paper as if there was no war” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 241).

All the while, international events also shaped the future of Palestine. Many in the West, responding to the actions of the Nazis against the Jews, were becoming much more supportive of the idea of Jews to be able to go Palestine. Many of the Zionists in the United States for example passed resolutions calling for unrestricted immigration to Palestine. Following this Biltmore Program, many Zionists in the United States worked to publicize the issue of a Jewish state in Palestine. And it seems that their efforts were effective: “President Harry Truman, from his arrival in the White House in 1945, through his reelection campaign of 1948, publicly endorsed the Biltmore Program, demonstrating not only humanitarian concerns but also an awareness of the growing power of the Zionist lobby within the Democratic Party. Truman’s commitment to the creation of a Jewish state was significant because the United States, with its expanding industrial economy and its unprecedented military might, emerged from the war as a global superpower capable of exerting immense pressure on its allies” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 242).

1947 UN Partition Plan

Britain, unable to control the domestic situation any longer, and turned to the UN for help. The United Nations, and more specifically, “A UN-appointed committee of representatives from various countries went to Palestine to investigate the situation. Although members of this committee disagreed on the form that a political resolution should take, the majority concluded that the country should be divided (partitioned) in order to satisfy the needs and demands of both Jews and Palestinian Arabs. At the end of 1946, 1,269,000 Arabs and 608,000 Jews resided within the borders of Mandate Palestine. Jews had acquired by purchase about 7 percent of the total land area of Palestine, amounting to about 20 percent of the arable land” (Beinin & Hajjar, 2014: 4).

Truman, in 1947, pushed a United Nations Special Committee on Palestine recommendation that Palestine be divided. And while they worried about whether there would be enough votes in the General Assembly, “Truman…launched an extensive lobbying effort on behalf of the majority report, and pro-Zionist members of Congress pressured UN delegates with the threats of the withdrawal of US economic assistance from their countries if they did not vote for the UNSCOP proposal” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 244). The proposal was supported in the United Nations on November 29th, 1947. However, Britain was not helpful in implementing the recommendation in the territory. Thus, coupled with a lack of a significant Arab representation during the discussions made many the implementation difficult; some also wondered whether the agreement was fair to both sides.

With regards to the land distribution for these two states, the 1947 UN partition plan designated 56 percent of the land to the Jewish state, and 43 percent for the Arab state (where Jerusalem, as well as Bethlehem would belong to neither state). Scholars explain that for the United Nations team, the reason for granting more land to the Jews was due to what they expected would be an increase in Jewish immigration (Beinin & Hajjar, 2014). While the Jewish leadership approved, there were beliefs among some that they would look for additional lands for the Jewish state. Meanwhile, the Palestinians, as well as neighboring Arab states, viewed the deal as unfair, and one that ignored the rights of Palestinians.

As a result of the conditions set force by the United Nations, local conflict broke out between Palestinian and Jewish Zionist forces. Shortly after this, in 1948, sensing the difficulties on the ground, Britain decided to leave Palestine. On May 14th, 1948, the Zionist leaders declared independence. The next day, forces from Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, as well as Transjordan attacked Israel. The Arab states, despite attacking Israel together, were far from unified. There were many internal, domestic issues that each were dealing with. In addition, the Arab states did not send many troops; in the first few weeks of the war, “from May 15 to June 11, 1948, the combined Arab armies numbered around 21,500, whereas the Haganah and its affiliated units fielded a force of some 30,000” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 248). In addition, the Israel forced did very well militarily, and over the year, the different Arab states each entered armistice agreements with Israel (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012). The new territorial landscape of Palestine looked a lot different than the 1947 United Nations recommendations.

Scholars continue to debate the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan. Some have continued to blame the Palestinians for their unwillingness to accept this deal, and that that was an opportunity for their own state, one in which they have only themselves to blame for not accepting the deal. Thus, some suggest that there were attempts to offer a serious and fair plan to resolve the conflict in Palestine at the time, but that it was the Palestinian leaders that were unwilling to agree to the proposal.

However, there has also been literature to counter this idea that the Palestinian leadership turned down a great deal by the United Nations. There are a couple of things to note. First, scholars have argued that there was a strong movement among some of the Zionist leaders that all of Palestine was to be part of the Jewish land, and that there was an attempt to do this through immigration, and then through “a period of expansion” (Khalidi, 2007: 99). There are also reports that the Haganah military was asked to have a plan for full takeover of Palestine if Britain was to leave during the Arab Revolt, as well as discussions among some leaders of the Zionist movement about the “transfer” of Palestinians out of the land (Khalidi, 2007: 99-100). Again, scholars argue that looking at the partition found it far from fair for the Palestinians who made up the majority of the population, but received a smaller percentage of the land (Khalidi, 2007).

The 1948 War

Some of the actions taken within this time period were steeped in controversy, and continue to be debated today.

Immediately after Israel declared independence, a number of Arab states (that included Egypt, Jordan, Syria, along with Iraq) declared war on Israel. Much of the fighting took place between May and June of 1948. In June of 1948, the Israeli forces received additional arms from Czechoslovakia, which helped them not only maintain their territories, but they also gained additional lands during the war (Beinin & Hajjar, 2014). The war itself was halted in 1949.

As Beinin & Hajjar (2014) explain, “The country once known as Palestine was now divided into three parts, each under a different political regime. The boundaries between them were the 1949 armistice lines (the “Green Line”). The State of Israel encompassed over 77 percent of the territory. Jordan occupied East Jerusalem and the hill country of central Palestine (the West Bank). Egypt took control of the coastal plain around the city of Gaza (the Gaza Strip). The Palestinian Arab state envisioned by the UN partition plan was never established” (5).

Palestinian Refugees in the 1948 War

One of the most noted aspects of the 1948 War was the high number of Palestinian refugees that fled the country. It was said that following the 1948 war, over 700,000 Palestinians were refugees. Scholars and policymakers continue to debate the reasons as to why the Palestinians left. Historically, many within the “pro-Israel” position have argued that the Palestinian citizens left on their own due to the war in general.

However, many Palestinians claimed that they were forced to leave, either through purposeful actions by the Israeli military, or through fear tactics used to reduce the number of Palestinians in the territory. It is important to note that while this debate continues on, there is at least some evidence to suggest that many Palestinians were forced to their homes. As Beinin & Hajjar (2014) write:

“One Israeli military intelligence document indicates that through June 1948 at least 75 percent of the refugees fled due to military actions by Zionist militias, psychological campaigns aimed at frightening Arabs into leaving, and dozens of direct expulsions. The proportion of expulsions is likely higher since the largest single expulsion of the war—50,000 from Lydda and Ramle— occurred in mid-July. Only about 5 percent left on orders from Arab authorities. There are several well-documented cases of massacresthatledtolarge-scaleArabflight.Themostinfamous atrocity occurred at Dayr Yasin, a village near Jerusalem, where the number of Arab residents killed in cold blood by right-wing Zionist militias was about 125.

This issue continues to be a center point for the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations today. For some within the Palestinian leadership and negotiators, they demand that Palestinian refugees (and descendants of the refugees) are granted “the right of return” to which they can go back to their historical homelands.

Others think this option is one that would not be agreed upon, given the population demographic issues that would be a part of this (with Israel not agreeing to millions of additional Palestinians into what is today Israel).

Thus, this issue about negotiating for the rights of Palestinian refugees is one (of many reasons) that agreeing to a peace deal has not happened.

Israel Palestine Conflict After the 1948 War

Following the 1949 Armistice agreements, Israel turned towards domestic issues within this newly founded state. Amongst the points of discussion and debate were effective approached to the increase in immigration (namely, discussions about farm land, housing, and issues of religion and culture). In addition, there were 160,000 Palestinians in Israel; the state recognized these Arabs (as long as they could prove their ties to Palestine), but many “Israeli authorities continued to regard the Arab citizens as a potential fifth column and adopted measures designed to prevent them from developing cohesive representative organizations. From 1948-1966, areas of Arab concentration were placed under the authority of a Military Administration that required Israeli Arabs to carry special identity cards and to obtain travel permits to go from one village to another” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 326). In addition, “During the first decade of Israeli statehood, the government expropriated thousands of acres of Israeli Arab land and forcibly relocated the displaced inhabitants. Israeli Arabs were further alienated by wage and employment discrimination and by their exclusion, because of their non-Jewishness, from the central mission of the Jewish state” (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012: 326). In the meantime, there were 960,000 Palestinian refugees (according to United Nations registration records) that were camped in areas such as Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and Gaza. Many of them did not have their land given the government takeover of their properties within Israel (Cleveland & Bunton, 2012).

Today, there are millions of Palestinian refugees–families who started out in “temporary” refugee camps that have essentially become permanent.

Frustrated with the political developments following World War I, and then in the decades leading to the declaration of Israeli statehood and the following 1948 War, some within the Palestinians looks to join fighting forces in attempts to carry out violent strikes against the newly established Israeli state and military. Thus, from the 1940s onwards, there were numerous attacks on Israeli installations. These attacks came from Palestinian territories such as the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, as well as from neighboring Jordan, Syria, and other countries…

In fact, one of the reasons for the domestic conflicts in Lebanon in the mid 1970s and then in the early 1980s had to do with Lebanese civil societies’ positions on the Palestinian forces. Some, particularly may within the Muslim communities, were rather supportive of groups like the Palestinian Liberation Organization, and their activities against the Israeli state. Others, such as many within the Maronite Christian community, were not as supportive, given the instability that it brought domestically within Lebanon (and knowing that Lebanon was increasingly becoming a place where Israel was responding to the Palestinian fighting forces).

The June War and the Israeli Palestinian Conflict

The 1967 June War (or the “Six-Day War”) is another important event to understand with regards to the Israel Palestine Conflict. During this time period, tensions between Israel and the various Middle Eastern states (such as Egypt, Jordan, Syria, etc…) were increasing. Nasser was engaged in a long multi-year war in Yemen, and then, in 1967, after hearing reports that Israel was planning on attacking Syria (these reports turned out to be inaccurate), Nasser began moving Egyptian troops toward the demilitarized zone separating Egypt and Israel. Israel, seeing this buildup, then commenced an air attack against Egyptian and Jordanian forces. Thus, “At 12:48 p.m. on June 5, four Israeli jets were descending on Jordan’s Mafraq air base to smash the country’s tiny air force, shortly after the entire Egyptian air force had been reduced to rubble” (Younes, 2012).

There are questions as to whether Israel’s actions here were offensive, or defensive, based upon Nasser’s actions. Israeli military argued that they felt this was a defensive action, given that they believed Nasser was going to attack Israel. Nasser, on the other hand, told Robert B. Anderson, US envoy to the United Arab Republic, ““Whether you believe it or not, we were in fear of an attack from Israel. We had been informed that the Israelis were massing troops on the Syrian border with the idea of first attacking Syria, there they did not expect to meet great resistance, and then commence their attack on the UAR[,]” to which Anderson responded, ““that it was unfortunate the UAR had believed such reports, which were simply not in accordance with the facts” (Hammond, 2010). There continues to be debate on whether Nasser received more sound intelligence of an Israeli attack (Hammond, 2010) or not.

Following the beginning of the Israeli military actions on these states, the Israeli military was not only able to defeat the Egyptian, Jordanian, Syrian, and Iraqi forces, but they also took over a number of territories that included the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula, Syria’s Golan Heights, Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem. Younes (2012) tells of how the Israeli military took East Jerusalem, saying:

The overall defense of Jerusalem was assigned to 27th Brigade, which was made up of three Regiments, headed by Brigadier Ali Ata al Hazza with the total combat troop strength of 1,500 men.

On the Israeli side, leading the assault on Jerusalem was the responsibility of Central Command headed by Major-General Narkiss with the preplanned deployment that called for cutting off Jerusalem from the bulk of the Jordanian army in the West Bank should Jordan enter the war.

The Israeli forces were much more organized and bigger than the Jordanian defenders, who, despite having fortified positions to defend, did not have the dynamism and the quality of the Israeli officer corps which had at its disposal tanks, artillery units and airborne paratroopers.

These actions are among the most controversial Israeli actions during the 1967 War. To many in the international community (and many international law scholars), Israel’s occupation of these different territories is illegal under international law. They point to the Geneva Conventions, as well as the United Nations resolution 242.

For example, Article 4 of the Geneva Conventions states that

Individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory to the territory of the Occupying Power or to that of any other country, occupied or not, are prohibited, regardless of their motive.

Nevertheless, the Occupying Power may undertake total or partial evacuation of a given area if the security of the population or imperative military reasons so demand. Such evacuations may not involve the displacement of protected persons outside the bounds of the occupied territory except when for material reasons it is impossible to avoid such displacement. Persons thus evacuated shall be transferred back to their homes as soon as hostilities in the area in question have ceased.

The Occupying Power undertaking such transfers or evacuations shall ensure, to the greatest practicable extent, that proper accommodation is provided to receive the protected persons, that the removals are effected in satisfactory conditions of hygiene, health, safety and nutrition, and that members of the same family are not separated.

The Protecting Power shall be informed of any transfers and evacuations as soon as they have taken place.

The Occupying Power shall not detain protected persons in an area particularly exposed to the dangers of war unless the security of the population or imperative military reasons so demand.

The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies (in ICRC).

And in Article 49 (6) of the Fourth Geneva Conventions (Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949.) states that: “The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.” (Steiman, 2013). The entire article reads:

Individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory to the territory of the Occupying Power or to that of any other country, occupied or not, are prohibited, regardless of their motive.

Nevertheless, the Occupying Power may undertake total or partial evacuation of a given area if the security of the population or imperative military reasons so demand. Such evacuations may not involve the displacement of protected persons outside the bounds of the occupied territory except when for material reasons it is impossible to avoid such displacement. Persons thus evacuated shall be transferred back to their homes as soon as hostilities in the area in question have ceased.

The Occupying Power undertaking such transfers or evacuations shall ensure, to the greatest practicable extent, that proper accommodation is provided to receive the protected persons, that the removals are effected in satisfactory conditions of hygiene, health, safety and nutrition, and that members of the same family are not separated.

The Protecting Power shall be informed of any transfers and evacuations as soon as they have taken place.

The Occupying Power shall not detain protected persons in an area particularly exposed to the dangers of war unless the security of the population or imperative military reasons so demand.

The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.

There are also additional points that further note the illegality of the settlements, such as the effect that the settlements have on the order and changes of the territory (Global Exchange, 2011). For example, Article 43 (which is an Annex to “Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907” notes that “The authority of the legitimate power having in fact passed into the hands of the occupant, the latter shall take all the measures in his power to restore, and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety, while respecting, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country” (in ICRC).

In addition, United Nations Resolution 242, which was passed in attempts to bring about peace to the conflict in the Middle East, states that, among other things:

“a. Withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict”

“b. Termination of all claims or states of belligerency and respect for and acknowledgement of the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of every State in the area and their right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force”

The debate has been on whether the states (Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) must recognize Israel in order for the land to be given back. However, many have criticized the belief that the Israeli government (under the Likud party) has any serious intention of giving the land back to the Palestinians (Black, 1992), particularly as they haves continued their settlement constructions in the West Bank and in East Jerusalem.

Israeli Settlements Following the 1967 War-Present

As mentioned above, one of the most contentious issues with regards to the Israel-Palestine conflict has to do with the continued construction of Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territories of the West Bank and East Jerusalem. As the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem explains, “Since 1967 Israel has established over a hundred settlements in the West Bank. In addition, there are dozens more settlement outposts that are not officially recognized by the authorities. These settlements were established on vast tracts of land taken from the Palestinians, in breach of international humanitarian law. The very existence of the settlements violates Palestinian human rights, including the right to property, equality, a decent standard of living and freedom of movement. Israel’s dramatic alteration of the West Bank map has precluded realization of Palestinians’ right to self-determination in a viable Palestinian state.”

Yet, the Israeli government continues to build settlements in The West Bank, as well as in East Jerusalem. In addition, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has even been upset when the United States leadership (under President Barack Obama) has suggested the peace talks will work off of the pre-1967 borders. Many believe he is angry about this because it would mean that Israel would have to give up these territories, territories that some within the hardline might view as historically belonging to the Jewish people.

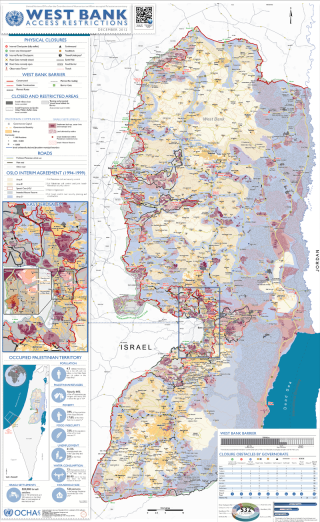

Here is another (more recent) map of the settlements and access restrictions that the Israeli government has placed on the West Bank.

According to B’Tselem, this area (known as Area C (the West Bank area) has 325,500 settlers in the area. As the human rights organization explains, “Area C covers 60% of the West Bank and is home to an estimated 180,000-300,000 Palestinians and to a settler population of at least 325,500 living in 125 settlements and approx. 100 outposts. Israel retains control of security and land-management in Area C and views the area as there to serve its own needs, such as military training, economic interests and settlement development. Ignoring Palestinian needs, Israel practically bans Palestinian construction and development. At the same time, it encourages the development of Israeli settlements through a parallel planning mechanism, and the Civil Administration turns a blind eye to settlers’ building violations.”

First Intifada

Recent Developments in the Israel Palestine Conflict

2008-2009 Israel Hamas War

On December 27th, of 2008, Israel began what they called “Operation Cast Lead.” This was an invasion into Gaza in order to fight Hamas. The Israeli military went after Hamas military installations. Then, on January 3rd, 2009, Israeli troops went into Gaza. The objective stated by the Israeli military was to disable any rocket activity from Gaza. Israel continued the invasion until January 18th, 2009. At the end of the conflict, 1440 Palestinians were killed, and 13 Israelis were killed. In terms of those killed, four of the 13 Israelis were citizens, and over half of the Palestinians killed were believed to be civilians (Zanotti, et. al., 2009) (with many children).

And because of this, there were many that were critical of Israel’s invasion, particularly with regards to the targets and scope of their operations. For example, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) , as well as the International Committee of the Red Cross called Israeli’s response “heavy” and stressed the challenges in carrying out humanitarian work, and in helping those in Gaza who were hurt (Zanotii et. al, 2009). Along with this, “

Additionally, there were multiple reports that Israeli fire hit U.N. buildings and/or compounds during the conflict, killing and injuring several shelter-seeking civilians. In the most deadly case, in which 43 Palestinians were killed by Israeli shelling on January 6 in response to fire from Palestinian militants, the reports turned out to be false—Israeli fire struck an area adjacent to, not inside, a U.N. compound. Getting timely and accurate reports of these and other occurrences proved challenging due to Israel’s barring of the international media from entering the territory independently during the conflict (only a small group was permitted into Gaza, accompanied by Israeli troops)” (Zanotti, et. al, 2009: 3).

2015-2016 Israel Palestine Conflict

The situation with regards to the conflict in Israel and Palestine continues in 2015 and 2016. In late 2015, there were a series of knife attacks being carried out in Israeli cities.

On March 12, 2016, in retaliation to rockets coming into southern Israel, the Israeli military carried out air attacks into Gaza. According to reports, “A six-year-old Palestinian girl and her 10-year-old brother were killed in the Gaza Strip by fragments from a missile fired by an Israeli aircraft” (Al Jazeera, 2016). The boy’s name was Yassin Abu Khosa, and he was ten years old. His sister, age six, was Israa Abu Khosa. According to reports, she “died in hospital on Saturday afternoon having succumbed to critical injuries sustained during the attack, Ashraf al-Qidra, spokesperson for Gaza’s Ministry of Health[,]” and Yassin died earlier (Al Jazeera, 2016).

The day after, United States Secretary of State John Kerry spoke about his desire to renew peace talks between the respective Israeli and Palestinian leadership. Kerry spoke about the need for peace between Israel and the Palestinians, but noted that the United States would not be able to reach this goal alone. He was quoted as saying: ““Obviously we’re all looking for a way forward. The United States and myself remain deeply committed to a two state solution. It is absolutely essential,” and that ““There’s not any one country or one person who can resolve this. This is going to require the global community, it will require international support.”

Other countries like France has stated that they will attempt to set up peace talks over the summer of 2016, with the understanding that not doing something could lead to the exposition of what has become a “powder keg” (Al Arabiya, 2016). However, it must be noted that while the United States leadership speaks about the importance of a peace deal, many point to their actions as suggesting that they are far from fair brokers with regards to the peace possibilities. For example, in the latest of a series of actions that have upset those thinking the US is an unfair actor, “Last year France failed to get the United States on board for a UN Security Council resolution to set parameters for talks between the two sides and a deadline for a deal” (The issue of the United States as unilaterally supporting Israel became more of an election topic when Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders criticized Israeli actions during the last war in Gaza).

New Calls for a Solution to the Israel-Palestine Conflict

Despite what has looked to be an inability for the international community solve the Israel-Palestine Conflict, there continue to be calls for peace. In late June, 2016, it was reported that over 200 Israeli “a group representing more than 200 retired leaders in Israel’s military, police, Mossad spy service and Shin Bet security agency presented a plan to help end the half-century occupation of the Palestinians through unilateral steps, including disavowing claims to over 90 percent of the West Bank and freezing Jewish settlement construction in such areas. The movement, called Commanders for Israel’s Security, reflects an increasingly widespread assessment that Israel is drifting catastrophically toward permanent entanglement with the Palestinians and conflict with the world community” (Perry & Federman, 2016).

There is a concern by this group that the hardline rule by Netanyahu continues to be a serious challenge to any peaceful solution to the Israel-Palestine Conflict. They call for immediate action, given the problems that continued conflict will lead to as it pertains to a lack of peace in the region.

For this group, they believe that a two state solution is one that needs to happen if there is to be peace, unless Israeli leaders are willing to grant voting rights to Palestinians. Plus, as international public opinion continues to move away from Israeli actions (this includes public opinion in the United States) (Perry & Federman, 2016), there may be more and more pressure for Israel to stop committing human rights abuses through their occupation of Palestinian lands.

Israel and Palestine: One State Solution?

Given the inability to come to a peace agreement for a separate Palestinian state, there has been a movement among some to abandon the idea of an independent state, and instead, either look towards a single state (including Palestinians within Israel), or a bi-national state. In fact, this was exactly what Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian President suggested could be possible. Abbas, speaking at the United Nations in September of 2017, not only said that “”The two-state solution is today in jeopardy,” but also that if independence is not an option, that they would have to “look for alternatives.” Abbas then went on to say, “”If the two-state solution were to be destroyed due to the creation of a one-state reality with two systems — apartheid,” and this would be a failure, and neither you, nor we, will have any other choice but to continue the struggle and demand full, equal rights for all inhabitants of historic Palestine”” (Federman, 2017).

Many believe that this approach, if it is one that the Palestinian leadership would really be willing to embrace, could put Israel in a very difficult position. The reason is that the Palestinians would demand every single right that is guaranteed for Israeli citizens. The belief by some is that accepting themselves as part of Israel, any failure to grant the Palestinians in the West Bank all rights would suggest a multi-tiered system of laws, something that is completely opposite to a liberal democracy. Mohammed Ishtayeh, who is a key advisor to Abbas, said of Abbas’ words, “”President Abbas sent a direct message to the U.S. administration, saying: Either you save the two-state solution or we are going to end up in one state where our people are going to ask for full rights”” (Federman, 2017).

However, despite Abbas’ comments, there are some that don’t see him move in this direction. Part of it is due to politics, and the power and role that Abbas has as a Palestinian leader. As Federman (2017) notes, “It seems unlikely that Abbas will follow through on his warning. The Palestinian president controls a budget of hundreds of millions of dollars, tens of thousands of jobs and travels the world with VIP status. His aides admit there are no immediate plans to disband the internationally backed Palestinian Authority.”

References

Abu-Manneh, B. (2007). The Rise of the Sanjak of Jerusalem in the Late Nineteenth Century, pages 40-50, in The Israel/Palestine Question: A Reader. Edited by Ilan Pappe. Routledge Press. Caplan, N. (2010). The Israel-Palestine Conflict: Contested Histories. Malden, Massachusetts. Wiley-Blackwell

Al Arabiya (2016). US says looking for way to move forward on Israel, Palestine peace. Al Arabiya. March 13, 2016. Available Online: http://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/middle-east/2016/03/13/US-says-looking-for-way-to-move-forward-on-Israel-Palestinian-peace.html

Al Jazeera (2016). Palestinian siblings killed in Israeli strikes on Gaza. Al Jazeera. March 12, 2016. Available Online: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/03/palestinian-siblings-killed-israeli-strikes-gaza-160312135229088.html

B’Tselem (2016). Area C. Available Online: http://www.btselem.org/topic/area_c

B’Tselem (2016). Settlements. Available Online: http://www.btselem.org/topic/settlements

Black, E. (1992). Resolution 242 and the aftermath of 1967. Chapter from Parallel Realities. Published in Minneapolis Star Tribune. PBS Frontline. Available Online: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/oslo/parallel/8.html

British White Paper (1939). British White Paper of 1939. Available Online: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/brwh1939.asp

Federman, J. (2017). Palestinian leader tries to put Trump on notice with warning. Associated Press, in Yahoo, September 24, 2017. Available Online: https://www.yahoo.com/news/palestinian-leader-tries-put-trump-notice-warning-171748639.html

Hammond, J.R. (2010). Israel’s attack on Egypt in June ’67 was not ‘preemptive.’ Foreign Policy Journal. July 4, 2010. Available Online: http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2010/07/04/israels-attack-on-egypt-in-june-67-was-not-preemptive/

Khalidi, W. (2007). Chapter 6: Revisiting the UNGA Partition Resolution, pages 97-114. In the Israel/Palestine Question: A Reader. Routledge Press.

Perry, D. & Federman, J. (2016). Israel’s Security Figures Take Aim at Hard-Line Netanyahu. ABC News. June 28, 2016. Available Online: http://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/israels-security-figures-aim-hard-line-netanyahu-40194104

Steiman, D. (2013). The settlements are illegal under international law. Jerusalem Post. Opinion. 12/29/2013. Available Online: http://www.jpost.com/Opinion/Op-Ed-Contributors/The-settlements-are-illegal-under-international-law-336507

Younes, A. (2012). 45 years after the 1967 war: How the Arabs lost Jerusalem. Al Arabiya. 01 August 2012. Available Online: http://english.alarabiya.net/articles/2012/08/01/229723.html

Zanotti, J. et. al. (2009). Israel and Hamas: Conflict in Gaza (2008-2009). Congressional Research Service. February 19, 2009. Available Online: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/R40101.pdf