Kurds in Iraq

In this article, we will discuss the history and current politics of the Kurds in Iraq. This article is one part of a series of article on Kurdish politics. We have written the article on the Kurds in Turkey, and will also have additional article on the Kurds in Syria and the Kurds in Iran. Given the interconnectedness of many historical and more contemporary events, it is difficult to understand Kurdish politics in these separate countries without knowing what has occurred in the other parts of the Middle East. Therefore, we urge you to look at the other articles as well, and then reflect upon how events in Iraq have shaped Kurdish politics in the country, and elsewhere in the region, and vice-versa.

The History of Kurdistan

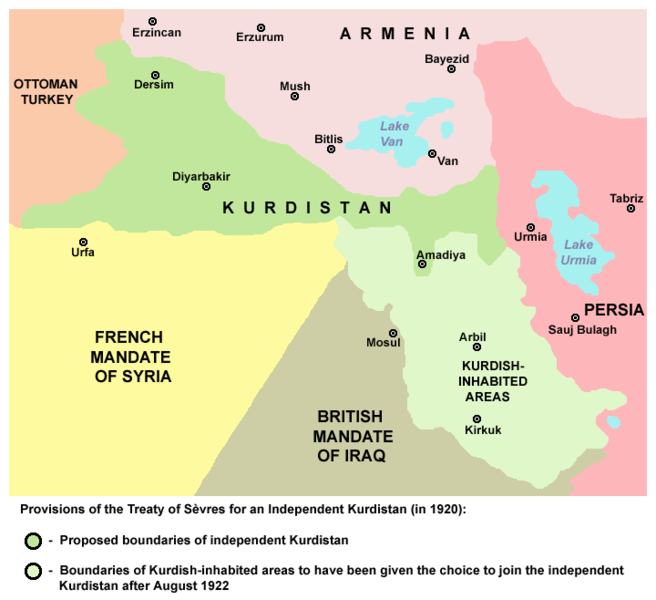

The more recent history of the region understood as Kurdistan can be examined with an eye on the events during (and immediately following) World War I. Britain and France, in their fight against Germany and the Ottoman Empire, were also interested in dividing the Middle East among one another. The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1915 established the areas in which Britain would have control, and areas that France would control.

For Britain, Iraq was one of the most important parts of the Middle East. In 1919, through the Paris Peace Conference, and then solidified in 1920 with the Treaty of Sevres, the new borders of the modern Middle East were established. Along with the creation of the modern day Iraq, there also existed proposed boundaries of Kurdistan.

In 1922, Britain had concerns that the Kurds would indeed try to break away and establish their own state. As a result, they attacked the Kurds to ensure that this would not happened. It can be argued that the British attacks on the Kurds in 1922 altered the potential history of the Kurds in Iraq and elsewhere. As Fantauzoo (2014) writes: “Without the First World War, Iraqi Kurds might today have their own state. Emboldened by the Anglo-French Declaration of November 1918, which promised the peoples of the Middle East ‘the setting up of national governments and administrations deriving their authority from the free exercise of the initiative and choice of the indigenous populations’, Iraqi Kurds believed mistakenly that self-governance was on the table for them, too. Yet Britain had little interest in segregating its newfound possession, the League of Nations Mandate for Iraq, and in the process losing the oil-rich fields of Mosul. So the Kurds revolted and declared the short-lived Kingdom of Kurdistan in September 1922, which was brutally suppressed by Britain in a series of aerial bombings that included even the use of mustard gas. By 1924 British bombings had pummeled the Kurds into submission. They surrendered to Britain and were subsequently reincorporated into the Kingdom of Iraq.”

The Kurds continued to be a part of Iraq throughout the post-World War I and WWI periods. Then, Kurdish national movements began to increase during the late 1950s and 1960s in Iraq. The Kurdish movement, while some argue it stalled prior to this time period, it was rejuvenated with the reformation of Kurdish troops under Mustafa Barzani. This, along with the rise of the Kurdish Democratic Party challenged the Iraqi authorities. Then, “In 1960 and early 1961…Barzani had gradually become dissatisfied with the lack of progress in meeting Kurdish demands. [Iraqi leader Abd al-Karim] Qasim began to encourage Barzani’s tribal enemies to move against him. Barzani moved from Baghdad to Barzan, where he could mobilize his tribal support and move against his opponents. At the end of August, much strengthened, he sent an ultimatum to Qasim demanding an end to authoritarian rule, recognition of Kurdish autonomy, and restoration of democratic liberties” (Marr, 2012).

Violence between the government and Barzani’s forces began in September of that year, and shortly after, the KDP party was banned. The civil war continued until 1963, in which “[d]uring the early days of 1963, contact was made between the Ba’thists and the KDP, and a tentative agreement appears to have been reached that if Qasim could be overthrown, Kurdish autonomy would be granted” (Marr, 2012: 106).

In 1970, the Kurds and the new leader of Iraq, Saddam Hussein (who came to power following the last Bath’ist coup in 1968), agreed to a deal that would grant the Kurds autonomy in exchange for peace. However, this deal was challenged in the 1970s, and then in 1979, following the Iranian Revolution. The Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomenei allowed the Kurds to carry out attacks against the Iraqi forces, and then retreat back into Iraq.

Saddam responded by not only fighting Iran and the Kurds, but at the end of the Iran-Iraq War, he gassed the Kurds, killing thousands. Then, there were further fears of government abuses during the Gulf War in the early 1990s. However, “[t]he region has been largely autonomous since the early 1990s, when the U.S. and allies set up a no-fly zone to protect the Kurds from Saddam Hussein” (Janssen & Szlanko, 2016).

Kurdish Political Parties in Iraq

There are a few different Kurdish political parties in Iraq. The primary parties in the Kurdish region of Iraq are:

- Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) is the party led by long time Kurdish leader Masoud Barzani. The KDP is still in power, as is Barzani, despite the ending of his term in August of 2015.

- PUK: The PUK has been described as “the second faction in Iraqi Kurdistan, and a fiefdom of the rival Talabani clan, led by Jalal Talabani, who was figurehead Iraqi president until this year. It is close to Iran, though not unfriendly to the West” (Spencer, 2015). The PUK is also increasing its ties with the PYD in Syria, and both the PUK and PYD are closer to the PKK in Turkey (ICG, 2015).

The Kurds and The Fight Against the Islamic State

The Kurdish forces in Iraq have been active in fighting the advances of the Islamic State. Not only are they willing to challenge this terror group, but they have also done rather well (more recently) in stopping ISIS advances, and also gaining their own territorial victories. The power and willingness to deter ISIS has led to domestic support by the Iraqi national government (whose own government forces have had a far than stellar showing in the country’s fight), as well as international actors such as the United States. The US has been willing to provide weapons to Kurdish forces. Since August of 2014, the United States has not only carried out anti-ISIS strikes, but they have also offered significant weapons to the Kurdish forces (ICG, 2015).

These weapons have been helpful to fight ISIS. While the Iraqi National Government forces have done a rather bad job of stopping ISIS, the Kurds have been much more successful. But it has come at a price, at least for the Iraqi National Government. With the rise of ISIS, the Kurdish forces–fearing additional territorial gains by the Islamic state, took what they saw as preemptive measures to protect areas under Iraqi national control. One of the cities that the Kurdish forces overtook was Kirkuk (ICG, 2015). Kirkuk was not included in the territories governed by the KRG in the 2004 Transitional Administrative Law (TWA) (ICG, 2015: 1). There are Kurds living in Kirkuk, and the area is important for the different Kurdish parties. In fact, “Kurdish leaders refer to the city of Kirkuk, located about sixty miles from the Iraqi Kurdish regional capital of Erbil, as their Jerusalem, alluding the to city’s disputed status among different ethnic groups decades after Saddam resettled the region and ousted thousands of Kurds in his “Arabization program.” Kirkuk has been the focal point of the Kurds’ disputes with Baghdad over territory and resources” (Council on Foreign Relations, 2015).

Again, some have suggested that these weapons, while helping fight ISIS, not have come at the price of empowering the Kurds in the region, but they have also aided the possibility that over time might help the Kurds’ power, which in turn could pose additional threats to the longevity of a unified Iraqi state. As the International Crisis Group (2015) argues: “Coalition military aid is premised on a belief that giving weapons and training to Kurdish forces, known as peshmergas, will in itself improve their performance against IS, a notion Kurdish leaders were quick to propagate. But the evolving state of Iraqi Kurdish politics makes for a rather more ambiguous picture: the dominant, rival parties, the KDP (Kurdistan Democratic Party) and PUK (Patriotic Union of Kurdistan), have been moving away from a strategic framework agreement that had stabilised their relationship after a period of conflict and allowed them to present a unified front to the central government as well as neighbouring Iran and Turkey” (i). The International Crisis Group writes about how ISIS has not unified these actors, saying:

IS’s arrival did little to bring the parties back together, much less revive the strategic agreement or encourage them to build institutions independent of their party-affiliated organs. Kurdish politics became yet more partisan. The conflict exacerbated simmering competition between and within both parties’ leaderships and tilted the internal balance toward the most security-minded politburo members, empowering them at the expense of those who traditionally had acted as a bridge between the rivals. President Barzani conducted his own policy, promoting himself as the leader of all Kurds, proposing to bring the Iraqi Kurdish peshmergas into a single command under his leadership and, more ambitiously, create a pan-Kurdish umbrella (including Syrian Kurdish peshmergas), and openly calling for independence, thus provoking criticism even within his own party. Inside the KDP, conflict with IS fanned the simmering competition among branches of the Barzani tribe, empowering security officials closest to the president who champion the leader-of-the-Kurds role and support the independence bid.

It is important to examine the rivalries between Kurdish parties further (7).

KDP and PUK Rivalry

While many not familiar with the conflict think of the Kurdish parties and forces as a unified group, differences do exist. In fact, there have been divisions between the KDP and PUK for years. As the International Crisis Group (ICG, 2015) explains, “[f]ollowing the first parliamentary elections in May 1992, they set themselves the task of governing, while keeping real power in the parties, supported by their respective security forces. Based on historical, cultural and linguistic differences, the KDP extended its reach throughout Erbil and Dohuk governorates, while the PUK’s stronghold was Suleimaniya, as well as, after the 2003 U.S. invasion, Kirkuk governorate, outside the Kurdish region in disputed territories” (5).

While they tried to govern together in the early 1990s, they were unable to do so. Thus, in 1996, with the help of the national military, the KDP removed the PUK from Erbil. Following the United States invasion in 2003, they worked to ensure that both parties would come together in a unified government. And while they have tried to work together in Erbil, and later in 2007 through a “strategic agreement” between the sides, they still have their own separate levers of power within Iraq (ICG, 2015). However, as of late, the rivalry has been one dominated by the KDP in Erbil. Even faction PUK groups such as Gorran have posed a challenge to the influence of the PUK in Iraq (ICG, 2015). Thus, due to a weakening PUK, the KDP has tried to even co-opt Gorran. The PUK, understanding their weaker role in Iraq, is looking to outside international actors such as Iran for greater support (ICG, 2015).

It is important to examine the regional rivalries that exist related to these groups. For example, while the Western and Arab-based international weapons coming into Iraq are intended to help the Kurds against ISIS, “weapons deliveries from a variety of donors are unilateral, mostly uncoordinated and come without strings regarding their distribution and use on the front lines. As a result, they have disproportionately benefited the KDP, which is dominant in Erbil, the region’s capital, and thus have pushed the PUK into greater reliance on Iranian military assistance and an alliance with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), the Kurdish rebel organisation in Turkey” (ICG, 2015: ii).

Thus, they have not been working completely in unison. In fact, “Party intelligence services enjoy separate sources of information, have developed privileged ties to different regional partners and share information selectively. Some view this as a primary factor behind the defeat in Sinjar in August, which resulted from inability or unwillingness to share evidence indicating that IS was about to attack” (ICG, 2015: 12).

It is for this reason that some scholars suggest “[c]oalition members, working in coordination, need instead to persuade Kurdish parties to complete the reunification of their parallel military, security and intelligence agencies within a single, non-partisan structure by empowering the KDP-PUK joint brigades and the peshmergas’ most professional elements; to cooperate with non-Kurdish actors in the disputed territories; and to develop a post-IS plan with the central government that cements security cooperation in these territories and moves forward the process of resolving their status through negotiation” (ICG, 2015).

Again, there are periods and places where they work together. But this all depends on their political interests for that particular situation. Where they can agree to divide territory, they do. Where they can’t they don’t. This can be seen with the importance of Kirkuk. As the ICG (2015) explains, “[c]oordination ends when interests diverge, as in Kirkuk, where both want to preserve and expand footholds, or where regional agendas strongly differ; thus, the KDP, which historically has had less influence in Kirkuk, insisted on a neutral com- mand structure in the area and deployed its forces at oil fields north west of the city” (10).

Iran and Turkey’s Ties to Kurdish Parties in Iraq

As mentioned, the KDP has established closer economic ties to Turkey, whereas Iran is closely linked to the PUK. Iran realizes that the PUK–weaker in Iraq, needs outside support to challenge the KDP. Thus, by stepping up and offering support, they might have additional influence in the country. Plus, they are also mindful of the fact that the KDP might move towards independence (ICG, 2015), which would hurt Iran’s overall influence and control of Iraq as a whole; they want the country to stay united, and they want to ensure that Iraq is economically prosperous. All of this helps maintain their leverage with some leaders in Baghdad. Thus, Iran was active in supporting the PUK when ISIS attacked in the summer of 2014. Interestingly, even the PKK was looking for Iranian support, particularly given Turkey’s delay in action in Iraq (ICG, 2015).

As we discuss in our article on the Kurds in Turkey, Ankara has historically been unwilling to work with Kurdish political parties. However, this has changed in recent years. Now, Erdogan has shifted Turkey’s position, and actually finds benefits to increased ties with the KDP in Erbil. Turkey and the KRG have established more oil deals with one another. However, this relationship has not without some distrust. Turkey was unhappy that the PKK were working with other Kurdish groups such as the PKK, which is currently in a civil war with the Turkish military. In addition, any comments about independence from the KDP worry Turkey, who wonder if the Kurds in their country will ask the same. Turkey believes that the economic relationship with Turkey is too important for the KDP to risk by moving to independence (ICG, 2015).

Both Iran and Turkey benefit by Iraq staying together, and therefore are looking to ensure that they continue to build relationships with the KDP and PUK respectively, but that neither will move for independence. What is making matters more complicated are the continued statements by Barzani for just that.

An Independent Kurdish State in 2016?

Given the development in Iraq in recent years, some of the Kurdish leaders in Iraq have called for the consideration of independent statehood for the Kurds in the country. For example, on February 3rd, 2016, W.G. Dunlop of Yahoo News reported that Massud Barzani, the leader of the KDP in Iraq, said that “”The time has come and the conditions are now suitable for the people to make a decision through a referendum on their future,” which suggests renewed statements about a possibility of an independent Kurdish state. He went on to say that “This referendum would not necessarily lead to (an) immediate declaration of statehood, but rather to know the will and opinion of the people of Kurdistan about their future.”

There is a belief that the Kurds are making this move now given the changing political conditions in Iraq and Syria. Part of this has to do with the unstable situation in Iraq; with the Islamic State still quite active in the country, some within the Kurdish population may be questioning Baghdad’s ability to maintain a stable Iraq.

In addition, the events in Syria seem to also be driving this discussion. As Dunlop (2016) explains, “Asked about the timing of the referendum, Ali Awni, a leader in Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party, said that “today is better than tomorrow,” but did not give a specific date. Awni said the Kurds have gained international sympathy from fighting the Islamic State jihadist group, and that now “we must show the world the will of our people (for) independence and the right of self-determination.”

The Challenges of an Independent Kurdish State in Iraq

These calls for Kurdish independence in Iraq are not new. These sorts of discussions have been taking place for years (and one could argue in some form, for decades), with renewed attention of late due to the rising role of Kurdish forces in their fight against the Islamic State in Iraq.

The largest obstacle to any serious (and meaningful) independence is the question of how the oil will be divided among Kurdistan and Baghdad. Most of the Iraq’s oil is in cities such as Baghdad, Basra (and other parts of southeastern Iraq), there is also a large amount of oil in the northern part of the country. For example, Iraq alone has 144 billion barrels of oil. The Kurdish Regional Government has about 4 billion barrels of oil, and Kirkuk has about 9 billion barrels of oil (CFR, 2015). In addition, the Iraqi government gave the KRG about 12 billion dollars per year-primarily from oil profits in late 2013 (Ottaway, 2013), and this number from the Iraqi government has increased about 17.93 billion dollars a year total in 2015 (CFR, 2015).

Through a revenue sharing agreement, the oil profits are distributed to different regions, and are not concentrated solely to the Kurdish government. However, Ottaway (2013) notes that with the development of their own pipeline in northern Iraq, they are able to bypass reliance and oversight from the Iraqi national government (despite Baghdad’s frustration and criticism of this) and sell the oil themselves, for their own profits. Currently, the Kurds and the Iraqi National Government are in an agreement in which Baghdad divides oil profits. However, with regards to the Kurds selling their oil through non-monitored pipelines, it seems that this is helpful for the Kurds, as “Kurdistan…intends to break Baghdad’s stranglehold over how its earnings from oil sales abroad are distributed, which is now becoming a highly contentious issue between the two sides. Turkey has agreed to allow Kurdistan to put those earnings into a special Turkish state bank account. The Kurdish regional government will then withdraw what it regards as its fair share before turning over the remainder to Baghdad, according to Turkish and Kurdish officials” (Ottaway, 2013: 1).

While oil has dropped significantly in recent months, in late 2013, it would have taken about 450,000 barrels a day for them to make the same money that the Iraqi national government was giving them. Having the independent pipelines (a Kurdish pipeline and a Turkish controlled one) (Ottaway, 2013) might, over time, decrease the interests that the Kurds have in staying with Iraq (on a side note, the drop in oil prices is also affecting the Kurdish war efforts in Iraq. It is said that “With oil prices hovering around $30 a barrel, the region is pulling in around $450 million a month, less than half what’s needed to cover $1.2 billion in expenditures. Kurdish officials say they need oil to return to $50 a barrel in order to pay salaries (Janssen & Szlanko, 2016)).

To make matters even more difficult with regards to the unity of Iraq, “[f]ederal forces fled positions in various northern areas in the summer of 2014 when facing an offensive by IS, allowing Kurdish forces to gain or solidify control over areas claimed by both them and Baghdad. Oil-rich Kirkuk province, which is mostly held by Kurdish peshmerga forces, will be a particular point of contention due to the wealth of natural resources there” (Dunlop, 2016). As the Kurds continue to not only fight off ISIS, but either keep or even expand their territory in Iraq and Syria, these developments could further challenge the idea of keeping Iraq as a unified country.

These sorts of comments are also likely to make other regional actors such as Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Turkey quite worried. As we have written here, Turkey is in its own civil war with the Kurds in the south. Furthermore, Erdogan does not want to see the Kurds in Syria successful, since this might galvanize the Kurds in Turkey. Therefore, while he has been willing to work with the Kurds in Iraq, and independent Kurdish state is likely to increase fears that Kurds in Turkey will demand similar political concessions (or, if not independence, autonomy, something not currently provided).

It is for this reason that there is a belief that Turkey will do what it can to ensure that an independent Kurdistan does not arise out of Iraq. It is not so much that they are concerned about what exists in Iraq, but rather, they are more interested (and concerned) about what an independent Kurdistan in Iraq will do to the Kurdish politics in Turkey.

As of now, Erdogan and the Turkish government have a large economic role in the success of the Kurdish Regional Government in the north; they are the primary buyers of KRG oil. They continue to promote a unified Iraq (Khalil, 2014), but the questions will be if Turkey is able to have the power to actually keep the Kurds within Iraq. As Ottaway (2013) explains, “Turkey is gambling that its new policy toward Kurdistan will actually head off its independence by making it so heavily dependent on Ankara that it cannot afford to go against Turkish opposition to its breakaway from Iraq. The Turks are dead set against autonomy for their own minority Kurdish population of at least 14 million as well as that for the 1.6 million Kurds in Syria. In fact the Erdogan government is working doggedly to integrate Turkey’s Kurds and voiced strong opposition to the recent proclamation of self-rule by separatist-minded Kurds in war-ravaged Syria” (2).

Independent Kurdistan: Political Maneuver by Barzani?

Along with the factors discussed above, we also have to consider other political motivations related to Barzani’s recent statements about the possibility of a Kurdish referendum for statehood. Ibrahim Al-Marashi, in thinking about the question of why this is happening now, argues that while the Kurdish-Baghdad relationship is part of the equation, we must also consider other factors such as his own rule, as well as low oil prices and related to this, the weakening economy in Kurdistan.

In order to understand the political motivations possibly behind these recent statements, we have to keep in mind the controversy regarding Barzani as the President of the Kurdish Regional Government. Barzani’s term limit, set to expire on August 19th, 2015 (Goudsouzian, 2015) was extended. Not everyone reacted with please. In fact, “In October of 2015 protests erupted over his extension of the term limit as president of the KRG, including in his traditional bastion of support, the city of Erbil. Media blackouts were imposed and Kurdish security forces were deployed to break up the protests” (Al-Marashi, 2016).

In addition, with low oil prices (the primary income for the KRG), many civil service workers are upset that they have not been paid. Thus, “[a]dvocating independence for the Kurds now serves as a convenient ploy to deflect domestic criticism over Barzani’s indefinite rule and economic crisis, and allowing him to gain the support of his own base, as well as constituencies loyal to the KRG’s other political parties, such as the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan and the opposition party Gorran (“Change”)” (Al-Marashi, 2016).

There is also a belief that this could be nothing but a move for more authority within the current state of Iraq. Al-Marashi (2016) has argued that given the Kurds overtook Kirkuk in 2014 (to prevent an ISIS attack on the city), Barzani may want to try to be using these latest statements as leverage for the Iraqi government to recognize Kirkuk as within the KRG. There may also be demands for more oil control by Barzani.

Divisions Between the Kurdish Political Parties

Interestingly, some have suggested that there are also increasing divisions within the Kurdish political elites in Iraq, and that “The [October 2015] protests are part of a bigger picture with many Kurdish analysts saying it is a revival of the dangerous powerplay between long-time rivals, Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) – and now, the relative newcomer, the Gorran (Change) Movement” (Goudsouzian, 2015). The different sides are accusing each other of politically-motivated activities, whether it is the protests, or, the Gorran Movement suggesting that oil revenues are not being shared by the KRG (under the KDP) (Goudsouzian, 2015).

Thus, these protests were very threatening to Barzani, and some even felt that they were an attempt to remove him from power. As Goudsouzian (2015) explains, “For their part, sources close to the PUK and Gorran suggest the protests erupted as a result of a perception that the KDP may be using public sector salaries as a bargaining chip in the negotiations. They posit that if there were an attempted coup in progress, it is the KDP mounting the coup on democracy by blocking entry to the parliament speaker. At a press conference on Monday, parliament speaker (and Gorran member) Yousef Mohammed called the move “a coup against the legitimacy of the parliament” and “a dangerous development for the political process in Kurdistan”.” Others have questioned how the protests turned violent, and why the government continues to not be open about what has happened (Goudsouzian, 2015).

Thus, with the current situation quite unstable in Iraq and Syria, and the history of politics between the KRG and Baghdad, it seems that they are far from resolving any outstanding issues as it pertains to the Kurds in Iraq and the future of Iraq as a whole. Furthermore, people in the Kurdish region are very upset, and yet, are tired with the existing political and economic situation, and frustrated that many feel they do not have a political voice (Goudsouzian, 2015).

References

Al-Marashi, I. (2016). The Kurdish referendum and Barzani’s political survival. February 4th, 2016. Al Jazeera. Available Online: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2016/02/kurdish-referendum-barzani-political-survival-iraq-160204111835869.html

Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) (2015). The Time of the Kurds: A CFR InfoGuide Presentation. Available Online: http://www.cfr.org/middle-east-and-north-africa/time-kurds/p36547#!/p36547

Dunlop, W.G. (2016). Iraq Kurd leader: ‘Time has come’ for statehood referendum. Yahoo News. February 3rd, 2016. Available Online: http://news.yahoo.com/iraq-kurd-leader-time-come-statehood-referendum-093222852.html

Fantauzzo, J. (2014). The First World War and the Middle East: One Hundred Years On. NATO Association of Canada. Available Online: http://natoassociation.ca/the-first-world-war-and-the-middle-east-one-hundred-years-on/

Goudsouzian, T. (2015). Analysis: Machiavellian politics in Iraqi Kurdistan. Al Jazeera. 13 October 2015. Available Online: http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/10/analysis-machiavellian-politics-iraqi-kurdistan-151013094035698.html

International Crisis Group (2015). Arming Iraq’s Kurds: Fighting IS, Inviting Conflict. Middle East Report N°158 | 12 May 2015. Available Online: http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/Middle%20East%20North%20Africa/Iraq%20Syria%20Lebanon/Iraq/158-arming-iraq-s-kurds-fighting-is-inviting-conflict.pdf

Janssen, B. & Szlanko, B. (2016). Son of Iraqi Kurdish leader calls for aid to battle IS. San Francisco Chronicle. February 9, 2016. Available Online: http://www.sfchronicle.com/news/world/article/Son-of-Iraqi-Kurdish-leader-calls-for-aid-to-6817878.php

Marr, P. (2012). The Modern History of Iraq, Third Edition. Boulder, Colorado. Westview Press.

Ottaway, D.B. (2013). Iraq’s Kurdistan Takes a Giant Step Toward Independence. Wilson Center, Viewpoints, No. 46, December 2013. Available Online: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/iraq_kurdistan_takes_giant_step_toward_independence.pdf

Spencer, R. (2015). Who are the Kurds? A User’s Guide to Kurdish Politics. The Telegraph. 05 July 2015. Available Online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/syria/11198326/Who-are-the-Kurds-A-users-guide-to-Kurdish-politics.html