Stanley Bruce chairing the League of Nations Council in 1936. Joachim von Ribbentrop is addressing the council, Commonwealth of Australia, public domain

League of Nations

In this article, we shall discuss the League of Nations. We shall examine the history of the League of Nations, the mandate of the League of Nations, as well as the various international relations issues that were discussed during the early meetings of the League. We shall also examine criticisms of the League of Nations. Lastly, we will examine the influence that the League of Nations had on the United Nations, which formed in the 1940s.

The History of the League of Nations

The League of Nations was formed following the end of the World War I. States in Europe, the United States, and elsewhere were concerned about the possibility of state aggression in the future, something that mirrored the horrors of World War I (History.com), and thus, the leaders of major powers came together to put together an international organization that would serve the function of international security. And while security concerns were not the only reasons that led to the formation of the League of Nations (there were also political and economic factors that drove states to create this international organization), they were the most pressing (Benes, 1932)..

There were attempts to advance organizations such as the League to Enforce Peace (Wertheim, 2011). However, one of the primary proponents to the League of Nations was United States President Woodrow Wilson. Wilson alluded to the idea of an international organization such as the League of Nations in a 1918 Speech to Congress (in a Joint Session) (UN). This 14 point speech included the foundation to the League of Nations. Namely, in article 14, Wilson stated that “A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike (Wilson, 1918, in Yale Law School). And following this point about an international organization, Wilson began advocating this idea throughout Europe. Specifically, “Wilson took up the cause with evangelical fervor, whipping up mass enthusiasm for the organization as he traveled to the Paris Peace Conference in January 1919, the first President to travel abroad in an official capacity” (US Department of State Office of the Historian, 2014). And along with his continued attention towards the development of an international organization (that eventually was the League of Nations), Wilson also played a crucial part in the writing of the Covenant of the League of Nations. In fact, “Wilson used his tremendous influence to attach the Covenant of the League, its charter, to the Treaty of Versailles. An effective League, he believed, would mitigate any inequities in the peace terms. He and the other members of the “Big Three,” Georges Clemenceau of France and David Lloyd George of Britain, drafted the Covenant as Part I of the Treaty of Versailles” (US Department of State Office of the Historian, 2014). The Covenant of the League of Nations raised a number of points with regards to the role of the international organization as it relates to international peace and security (see the bottom of this article for a complete text to the Covenant on the League of Nations).

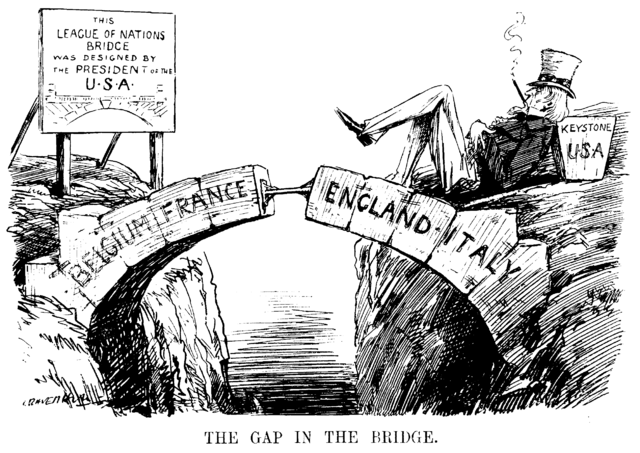

The Gap in the Bridge. Cartoon about the absence of the USA from the League of Nations, depicted as the missing keystone of the arch. The cigar also symbolizes America (Uncle sam) enjoying its wealth, (10 December 1919), Punch Magazine 10 December 1919 Raffo, P. (1974). The League of Nations. London: The Historical Association, p. 7, Leonard Raven-Hill, public domain

Yet despite the formation of the League of Nations, one of the flaws of the organization was that the United States Senate never ratified the Covenant of the League of Nations, nor the Treaty of Versailles (History.com). And following this unwillingness to pass the Covenant of the League of Nations, “Wilson suffered a severe stroke in the fall of that year, which prevented him from reaching a compromise with those in Congress who thought the treaties reduced U.S. authority. In November, the Senate declined to ratify both. The League of Nations proceeded without the United States, holding its first meeting in Geneva on November 15, 1920” (History.com).

The issue in the United States Congress had much to do with the idea of US sovereignty, and what the commitment to the League of Nations would do to the notion of sovereignty. Many of the tensions within the Congress on the issue of the League of Nations was due to the disagreements between Wilson and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge. Lodge, who was in stark opposition with United States joining the League of Nations, attempted to stall discussions on the Treaty of the League of Nations. He did this by “using delaying tactics as spending two weeks reading its entire contents aloud before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee” (Ladenburg, 2007: 54). However, this only led to Wilson digging in further, and beginning to tour the United States with the hopes of making his case for the importance of the League of Nations. However, he got sick during this campaign, having a stroke. Because the stroke paralyzed part of his body, he was unable to be active during the continued discussion on the Treaty of the League of Nations (Ladenburg, 2007).

The primary concern that Congress had with regards to the Treaty of the League of Nations stemmed from Article 10, which stated that “The Members of the League undertake to respect and preserve as against external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all Members of the League. In case of any such aggression or in case of any threat or danger of such aggression the Council shall advise upon the means by which this obligation shall be fulfilled[,]” and more specifically, around what role and responsibility the United States would have with regards to the contents of the article. For Wilson, the United States needed to be active to protect states against any aggressor. However, others, such as Lodge, believed that signing onto this Treaty of the League of Nations would reduce US sovereignty, particularly with regards to decision-making with regards to war (Ladenburg, 2007). Namely, he said that he was most concerned about “the right of other powers to call out American troops and American ships to go to any part of the world, an obligation we are bound to fulfill under the terms of the treaty” (Ladenburg, 2007). Lodge went on to say that “I know the answer full well–that of course they could not be sent without action by Congress. Congress would have no choice of acting in good faith, and if under Article X any member of the League summoned us, there would be no escape except by a breach of faith. Is it too much to ask that provision should be made that American troops and American ships should never be sent anywhere or ordered to take part in any conflict except after the deliberate (careful) action of the American people expressed through their chosen representatives in Congress?…” (Ladenburg, 2007: 55).

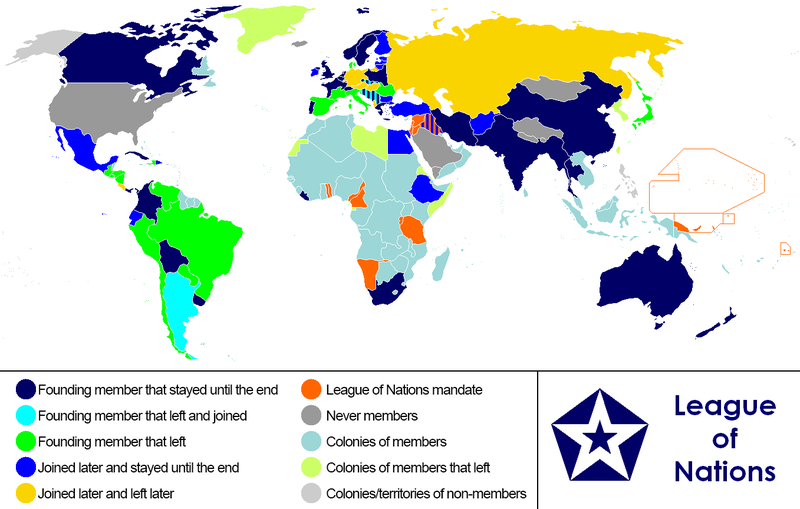

Anachronous map of the world between 1920 and 1945 which shows the The League of Nations and the world, Reallyjoel, CC 3.0

League of Nations Structure

In terms of the organizational structure of the League of Nations, “The League’s main organs were an Assembly of all members and a Council, made up of five permanent members and four rotating members, along with an International Court of Justice. Most importantly, for Wilson, the League would guarantee the territorial integrity and political independence of member states, authorize the League to take “any action…to safeguard the peace,” establish procedures for arbitration and create the mechanisms for economic and military sanctions” (US Department of State Office of the Historian, 2014). Furthermore, the League of Nations had three branches of governance. These were:

-

A council and an Assembly to act as a legislative branch. The Council consisted of the United States, Great Britain, France, Italy, and Japan as well as the representatives of nine of the smaller states. All nations in the League had a single vote in the Assembly…

-

A Secretariat, which in some ways would act as an executive branch, carrying out day-to-day function of the League. The Secretariat, however, commanded no army or navy, and thus could not carry out the wishes or decrees of the Assembly or the Council. Its power lay in its willingness of members to act in its name.

-

The Permanent Court of International Justice which in some ways acted as a judicial branch. All members of the League were pledged to refer disputes to the Court or to the League’s Council. In the sense that the Council was also empowered to call for actions from member nations it, too, could be considered part of the League’s judicial branch” (Ladenburg, 2007: 53-54).

Was the League of Nations Effective?

One of the highly asked questions with regards to the League of Nations was with regards to its effectiveness. Namely, did the League of Nations do what it was created to do? As we shall see, there were many things that the League of Nations did that helped with regards to international peace and security. However, as we shall see, there were also a number of inactions or flaws within the League of Nations. Beginning with the successes of the League of Nations, the mere fact that they were able to get states to agree to an international organization based on joint security and counter aggressors could be viewed as a great success. When looking at state action prior to the formation of the League of Nations, it was seen as one of self-interest of that said state. The League of Nations made them view themselves in a much wider context, one of a global community of states (Benes, 1932). Moreover, it was not enough to just know this, but to actually takes steps to act together to ensure these principles was a great victory for the League of Nations (Benes, 1932). One has to remember that the League of Nations was quite different than what the world saw before its formation (Pearson, 2013), and it did alter the way international relations were conducted.

One of the other major successes of the League of Nations has been the formation of the Permanent Court of International Justice, and its ability to ensure the principles of the Covenant of the League of Nations, and as a mechanism for arbitration (Benes, 1932). Benes (1932) cites a dispute of the Aland Islands between Finland and Sweden, as well as another territorial dispute between Poland and Lithuania (over a territory named Vilna) and the ability of the League of Nations to effectively calm concerns by the various parties in each case. In fact, the League of Nations was active in helping resolve a number of disputes by countries (see Benes, 1932, and his discussion on arbitration regarding cases between Italy and Greece in 1923, and Greece and Bulgaria (1925)). It has been argued that “[d]uring its first decade the League of Nations made a hugely valuable contribution to the management of the post-war international system. Throughout the 1920s it provided mediation in border disputes at various times between such neighbors as Finland and Sweden, Yugoslavia and Albania, and Hungary and Czechoslovakia. It also initiated what were in effect international peacekeeping operations” (4).

For example, the League of Nations played a critical role in the territorial dispute between France and Germany over Saar. This territory was in Germany, but following the war, was “internationalized”. However, France had an interest in the territory, wanting to incorporate Saar into France. But with the involvement of the League of Nations, “the French government was prevailed on to accept the economic benefits of the Saar but with the territory placed under a League of Nations administration until 1935…This was in effect a precursor to the UN’s provision of temporary administrations in…disputed regions” (5).

In addition to this role of arbitration among states, writing in 1932, Benes argues that the Permanent Court was very important for upholding issues of international peace and security. Specifically, he writes that

“the importance of the concrete work for peace accomplished the Permanent Court is beyond all dispute. The verdicts which it has given on actual disputes brought before it, either in virtue of international treaties or at the instigation of the Council, as well as the recommendations which it has made in individual cases at the request of the Council, are highly important acts in the cause of peace. The authority of the Court has become a living factor for peace, recognized as such by many nations, who by accepting the facultative clause have obligated themselves to apply to the Court for a solution of most international disputes of a legal nature” (70).

One of the other top successes with regards to the League of Nations was its ability to control weapons trading. For example, the League of Nations also had a goal of disarmament, and they are able to set norms about disarmament that has continued to last in the international system (Stone, 2000). Plus, we have to remember the context of which this idea of controlling weapons was established. As Stone (2000) explains “[t]hat a state should limit its arms exports for the sake of the peace and security of other states is a modern innovation” (214) (For a full discussion on the history of arms control, see Stone’s (2000) article entitled The League of Nations’ Drive to Control the Global Arms Trade). For example, the League of Nations called on states to back the Convention for the Control of the Trade in Arms and Ammunition” (Stone, 2000: 219), and even though it was not ratified (many faulted the United States for this as well, it it believed to have shaped later discussions and international actions about arms control (Stone, 2000).

Sesión De La Sociedad De Naciones (League of Nations) Sobre Manchuria 1932,

Robert Sennecke (1885–1940), public domain

Failures of the League of Nations

Despite the noted successes of the League of Nations mentioned above, there were also many failures of the League of Nations. To begin, one can even look at the initial creation of the League of Nations. For example, Woodrow Wilson was very passionate about creating the League of Nations. But many did not share the same enthusiasm. For example, “Clemenceau, Lloyd-George and Orlando were rather interested in their own affairs. For example intended Clemenceau to send only a few deputies to the committee of the League with the main aim of getting concessions in the Rhineland question” (Epoche, 2004, in Kliesch, 2005: 1).

Moreover, it has been argued that the League of Nations did not have the adequate tools to actually enforce issues of collective security. For example, the League of Nations was unable to respond effectively to Japan’s invasion into China. In fact, some have suggested that the United States, not being a member, made it even more difficult for the League of Nations to carry out economic punishments against Japan (Ebegbulem, 2011). Regarding this issue of ineffectiveness on sanctions, Kleitsch (2005) explains that “To put the high aims into practice the League of Nation would have needed a strong executive body, but it had only a few weapons it could use against aggressive countries: Negotiations, economic sanctions and, in extreme case building up an army, which was never applied. Particularly bad was, that it’s main weapon, economic sanctions, was weakened by the fact that three major economies weren’t members from the League’s birth. After WW1 the USA, the world’s biggest economy, went into it’s policy of isolation again in order to keep out of European affairs” (1). Plus, after the Great Depression, there was a concern that sanctions (such as freezing trade with certain countries) would exacerbate an already horrible economy (Kleitsch, 2005).

But above anything else, many have suggested that the greatest problem with the League of Nations being effective was that there existed a “lack of commitment of it’s members which led, step by step, to a loss of its credibility” (Kleitsch, 2005). Japan, a member state, attacked China. The League of Nations could not stop them, and Japan actually ended up leaving the League of Nations. A great complaint against the Leagueof Nations was that “[f]or the big European power in the League Council this conflict in a remote part of Asia was simply not important enough in the calculation of their own national interests to justify any robust action” (Pearson, 2013: 7).

Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia also greatly damaged the credibility of the League of Nations as an organization that was meant to uphold peace and security, and this too was due to a failure to enact military action, or strenuous sanctions. Italy, a member state, carried out an unjust offensive on Ethiopia in the year 1935. And while the League of Nations did implement sanctions against Italy, they were unable to do much more, given Italy’s ability to use a veto against stringent actions. In addition, Italy was seen as a potential ally to France and Britain, against the rising power of Germany (Ebegbulem, 2011). Also, with the case of Italy, “[n]ot all League countries supported the decision and carried on trading with Italy and the selection of banned goods proved also rather ineffective: War important oil was not part of it. To make things worse for the League secret diplomacy re-appeared. Britain and France negotiated alone with Italy and developed the Hoare-Laval plan. But this failed too and Italy went on to capture the whole of Ethiopia” (Kleitsch, 2005: 2).

From the League of Nations to the United Nations

In the early formation of the United Nations, there was little direct reference to the League of Nations. In addition, many continued to emphasize differences between the two (Goodrich, 1947). And it was “[o]n April 18, 1946, the League Assembly adjourned after taking the necessary steps to terminate the existence of the League of Nations and transfer its properties and assets to the United Nations” (Goodrich, 1947: 3). However, despite the importance of the League of Nations to the United Nations, there was little mention of the League of Nations during the San Francisco conference in February of 1945. Goodrich, in 1947, writes about this, saying that “…from the addresses and debates at the San Francisco Conference, the personnel assembled for the Conference Secretariat, and the organization and procedure of the Conference, it would have been quite possible for an outside observer to draw the conclusion that this was a pioneer effort in world organization” (4).

Yet Despite all of the inefficiencies of the League of Nations in the 26 years that it was in existence, a number of institutions and ideas from the League of Nations were implemented into the formation of the United Nations. In fact, regarding these similarities, Goodrich (1947) writes that

“[o]bviously, any useful comparison of the League and the United Nations must be based on the League system as it developed under the Covenant. If that is done, it becomes clear that the gap separating the League of Nations and the United Nations is not large, that many provisions of the United Nations system have been taken directly from the Covenant, though usually with changes of names and rearrangements of words, that other provisions are little more than codifications, so to speak, of League practice as it developed under the Covenant, and that still other provisions represent the logical development of ideas which were in process of evolution when the League was actively functioning” (5).

For example, Goodrich, writing in 1947, saw the the League of Nations and the United Nations both similar with regards to carrying out peace settlements. IN addition. both the League of Nations and the General Assembly could make comments with regards to issues of peace. And even in 1947, people criticized the League of Nations assembly with regards to enforcement capabilities. Interesting, Goodrich asked if the United Nations would be any better? Many have wondered as to their level of effectiveness, even with capabilities through Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter.

References

Benes, E. (1932). The League of Nations: Successes and Failures. Foreign Affairs, October 1, 1932, pages 66-80.

Ebegbulem, J.C. (2011). The Failure of Collective Security in the Post World Wars I and II International System. Transcience, Vol. 2, No. 2, pages 23-29.

Epoche, G. (2004). Der Erste Weltkrieg, Chief editor: Peter-Mathias Garde, Gruner + Jahr, Hamburg (Germany), 2004, ISBN 3-570-19451-5

Goodrich, L.M. (1947). From League of Nations to United Nations. International Organization, Vol. 1, No. 1, pages 3-21.

History.com. January 10, 1920. League of Nations. Instituted. Available Online: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/league-of-nations-instituted

Kliesch, C. (2005). Why did the League of Nations Fail and Why Did it Matter? 25-10-2005, pages 1-3.

Ladenburg, T. (2007). Chapter 12: Woodrow Wilson and the League of Nations, pages 53-56. Available Online: http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/teachers/lesson_plans/pdfs/unit8_12.pdf

Pearson (2013). “The ‘Failure” of the League of Nations and the Beginnings of the UN.” Pearson Higher Education, pages 3-12. Pearson Education.

Stone, D.R. (2000). Imperialism and Sovereignty: The League of Nations’ Drive to Control the Global Arms Trade. Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 35, No. 2, pages 213-230.

United Nations. Chronology: Available Online: http://www.unog.ch/80256EDD006B8954/(httpAssets)/3DA94AAFEB9E8E76C1256F340047BB52/$file/sdn_chronology.pdf

United States Department of State Office of the Historian (2014). Milestones: 1914-1920. The League of Nations, 1920. Available Online: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/league

Wertheim, S. (2011). The League That Wasn’t: American Designs for a Legalist-Sanctionist League of Nations and the Intellectual Origins of International Organization, 1914-1920. Diplomatic History: The Journal of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations. Vol. 35, No. 5, pages 797-836.

Yale Law School. President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Available Online: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/wilson14.asp

League of Nations Documents

Treaty of Versailles and the Covenant on the League of Nations

“PART 1

THE COVENANT OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS

THE HIGH CONTRACTING PARTIES

In order to promote international co-operation and to achieve international peace and security

by the acceptance of obligations not to resort to war,

by the prescription of open, just and honourable relations

between nations,

by the firm establishment of the understandings of international law as the actual rule of conduct among Governments,

and

by the maintenance of justice and a scrupulous respect for all treaty obligations in the dealings of organised peoples

with one another,

Agree to this Covenant of the League of Nations.

ARTICLE 1.

The original Members of the League of Nations shall be those of the Signatories

which are named in the Annex to this Covenant and also such of those other

States named in the Annex as shall accede without reservation to this Covenant.

Such accession shall be effected by a Declaration deposited with the Secretariat

within two months of the coming into force of the Covenant Notice thereof shall

be sent to all other Members of the League.

Any fully self- governing State, Dominion, or Colony not named in the Annex may become a Member of the League if

its admission is agreed to by two- thirds of the Assembly provided that it shall give effective guarantees of its sincere

intention to observe its international obligations, and shall accept such regulations as may be prescribed by the League

in regard to its military, naval, and air forces and armaments.

Any Member of the League may, after two years’ notice of its intention so to do,

withdraw from the League, provided that all its international obligations and

all its obligations under this Covenant shall have been fulfilled at the time of

its withdrawal.

ARTICLE 2.

The action of the League under this Covenant shall be effected through the

instrumentality of an Assembly and of a Council, with a permanent Secretariat.

ARTICLE 3.

The Assembly shall consist of Representatives of the Members of the League.

The Assembly shall meet at stated intervals and from time to time as occasion may require at the Seat of the League or

at such other place as may be decided upon. The Assembly may deal at its meetings with any matter within the sphere of

action of the League or affecting the peace of the world. At meetings of the

Assembly each Member of the League shall have one vote, and may not have more

than three Representatives.

ARTICLE 4.

The Council shall consist of Representatives of the Principal Allied and

Associated Powers, together with Representatives of four other Members of the

League. These four Members of the League shall be selected by the Assembly from

time to time in its discretion. Until the appointment of the Representatives of

the four Members of the League first selected by the Assembly, Representatives

of Belgium, Brazil, Spain, and Greece shall be members of the Council.

With the approval of the majority of the Assembly, the Council may name additional Members of the League whose

Representatives shall always be members of the Council; the Council with like approval may increase the number of

Members of the League to be selected by the Assembly for representation on the Council.

The Council shall meet from time to time as occasion may require, and at least once a year, at the Seat of the League, or

at such other place as may be decided

upon.

The Council may deal at its meetings with any matter within the sphere of

action of the League or affecting the peace of the world.

Any Member of the League not represented on the Council shall be invited to send a Representative to sit as a member

at any meeting of the Council during the consideration of matters specially affecting the interests of that Member of the

League.

At meetings of the Council, each Member of the League represented on the Council

shall have one vote, and may have not more than one Representative.

ARTICLE 5.

Except where otherwise expressly provided in this Covenant or by the terms of

the present Treaty, decisions at any meeting of the Assembly or of the Council

shall require the agreement of all the Members of the League represented at the

meeting.

All matters of procedure at meetings of the Assembly or of the Council,

including the appointment of Committees to investigate particular matters, shall

be regulated by the Assembly or by the Council and may be decided by a majority

of the Members of the League represented at the meeting.

The first meeting of the Assembly and the first meeting of the Council shall be summoned by the President of the

United States of America.

ARTICLE 6

The permanent Secretariat shall be established at the Seat of the League. The

Secretariat shall comprise a Secretary General and such secretaries and staff as

may be required.

The first Secretary General shall be the person named in the

Annex; thereafter the Secretary General shall be appointed by the Council with

the approval of the majority of the Assembly.

The secretaries and staff of the Secretariat shall be appointed by the Secretary General with the approval of the Council.

The Secretary General shall act in that capacity at all meetings of the

Assembly and of the Council.

The expenses of the Secretariat shall be borne by the Members of the League in accordance with the apportionment of

the expenses of the International Bureau of the Universal Postal Union.

ARTICLE 7.

The Seat of the League is established at Geneva.

The Council may at any time decide that the Seat of the League shall be established elsewhere.

All positions under or in connection with the League, including he Secretariat, shall be open equally to men and

women.

Representatives of the Members of the League and officials of he League when engaged on the business of the League

shall enjoy diplomatic privileges and immunities.

The buildings and other property occupied by the League or its officials or by Representatives attending its meetings

shall be inviolable.

ARTICLE 8.

The Members of the League recognise that the maintenance of peace requires the

reduction of national armaments to the lowest point consistent with national

safety and the enforcement by common action of international obligations.

The Council, taking account of the geographical situation and circumstances of each State, shall formulate plans for

such reduction for the consideration and action of the several Governments.

Such plans shall be subject to reconsideration and revision at least every ten years.

After these plans shall have been adopted by the several Governments, the limits of armaments therein fixed shall not

be exceeded without the concurrence of the Council.

The Members of the League agree that the manufacture by private enterprise of munitions and implements of war is

open to grave objections. The Council shall advise how the evil effects attendant upon such manufacture can be

prevented, due regard being had to the necessities of those Members of the League which are not able to manufacture

the munitions and implements of war necessary for their safety.

The Members of the League undertake to interchange full and frank information as to the scale of their armaments,

their military, naval, and air programmes and the condition of such of their industries as are adaptable to war-like

purposes.

ARTICLE 9

A permanent Commission shall be constituted to advise the Council on the

execution of the provisions of Articles 1 and 8 and on military, naval, and air

questions generally.

ARTICLE 10

The Members of the League undertake to respect and preserve as against external

aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all

Members of the League. In case of any such aggression or in case of any threat

or danger of such aggression the Council shall advise upon the means by which

this obligation shall be fulfilled.

ARTICLE 11.

Any war or threat of war, whether immediately affecting any of the Members of

the League or not, is hereby declared a matter of concern to the whole League,

and the League shall take any action that may be deemed wise and effectual to

safeguard the peace of nations. In case any such emergency should arise the

Secretary General shall on the request of any Member of the League forthwith

summon a meeting of the Council.

It is also declared to be the friendly right of each Member of the League to bring to the attention of the Assembly or of

the Council any circumstance whatever affecting international relations which threatens to disturb international peace

or the good understanding between nations upon which peace depends.

ARTICLE 12.

The Members of the League agree that if there should arise between them any

dispute likely to lead to a rupture, they will submit the matter either to

arbitration or to inquiry by the Council, and they agree in no case to resort to

war until three months after the award by the arbitrators or the report by the

Council.

In any case under this Article the award of the arbitrators shall be

made within a reasonable time, and the report of the Council shall be made

within six months after the submission of the dispute.

ARTICLE 13.

The Members of the League agree that whenever any dispute shall arise between

them which they recognise to be suitable for submission to arbitration and which

cannot be satisfactorily settled by diplomacy, they will submit the whole

subject-matter to arbitration.

Disputes as to the interpretation of a treaty, as to any question of international law, as to the existence of any fact which

if established would constitute a breach of any international obligation, or as to the extent and nature of the reparation

to be made or any such breach, are declared to be among those which are generally suitable for submission to

arbitration.

For the consideration of any such dispute the court of arbitration to which the case is referred shall be the Court agreed

on by the parties to the dispute or stipulated in any convention existing between them.

The Members of the League agree that they will carry out in full good faith any award that may be rendered, and that

they will not resort to war against a Member of the League which complies therewith. In the event of any failure to

carry out such an award, the Council shall propose what steps should be taken to give effect thereto.

ARTICLE 14.

The Council shall formulate and submit to the Members of the League for adoption

plans for the establishment of a Permanent Court of International Justice. The

Court shall be competent to hear and determine any dispute of an international

character which the parties thereto submit to it. The Court may also give an

advisory opinion upon any dispute or question referred to it by the Council or

by the Assembly.

ARTICLE 15.

If there should arise between Members of the League any dispute likely to lead

to a rupture, which is not submitted to arbitration in accordance with Article

13, the Members of the League agree that they will submit the matter to the

Council. Any party to the dispute may effect such submission by giving notice of

the existence of the dispute to the Secretary General, who will make all

necessary arrangements for a full investigation and consideration thereof.

For this purpose the parties to the dispute will communicate to the Secretary

General, as promptly as possible, statements of their case with all the relevant

facts and papers, and the Council may forthwith direct the publication thereof.

The Council shall endeavour to effect a settlement of the dispute, and if such

efforts are successful, a statement shall be made public giving such facts and

explanations regarding the dispute and the terms of settlement thereof as the

Council may deem appropriate.

If the dispute is not thus settled, the Council either unanimously or by a majority vote shall make and publish a report

containing a statement of the facts of the dispute and the recommendations which are deemed just and proper in regard

thereto.

Any Member of the League represented on the Council may make public a statement of the facts of the dispute and of

its conclusions regarding the same.

If a report by the Council is unanimously agreed to by the members thereof other than the Representatives of one or

more of the parties to the dispute, the Members of the League agree that they will not go to war with any party to the

dispute which complies with the recommendations of the report.

If the Council fails to reach a report which is unanimously agreed to by the members thereof, other than the

Representatives of one or more of the parties to the dispute, the Members of the League reserve to themselves the right

to take such action as they shall consider necessary for the maintenance of right and justice.

If the dispute between the parties is claimed by one of them, and is found by the Council, to arise out of a matter which

by international law is solely within the domestic jurisdiction of that party, the Council shall so report, and shall make

no recommendation as to its settlement.

The Council may in any case under this Article refer the dispute to the Assembly. The dispute shall be so referred at the

request of either party to the dispute, provided that such request be made within fourteen days after the submission of

the dispute to the Council.

In any case referred to the Assembly, all the provisions of this Article and of Article 12 relating to the action and

powers of the Council shall apply to the action and powers of the Assembly, provided that a report made by the

Assembly, if concurred in by the Representatives of those Members of the League represented on the Council and of a

majority of the other Members of the League, exclusive in each case of the Representatives of the parties to the dispute

shall have the same force as a report by the Council concurred in by all the members thereof other than the

Representatives of one or more of the parties to the dispute.

ARTICLE 16.

Should any Member of the League resort to war in disregard of its covenants

under Articles 12, 13, or 15, it shall ipso facto be deemed to have committed an

act of war against all other Members of the League, which hereby undertake

immediately to subject it to the severance of all trade or financial relations,

the prohibition of all intercourse between their nations and the nationals of

the covenant-breaking State, and the prevention of all financial, commercial, or

personal intercourse between the nationals of the covenant-breaking State and

the nationals of any other State, whether a Member of the League or not.

It shall be the duty of the Council in such case to recommend to the several

Governments concerned what effective military, naval, or air force the Members

of the League shall severally contribute to the armed forces to be used to protect the covenants of the League.

The Members of the League agree, further, that they will mutually support one another in the financial and economic

measures which are taken under this Article, in order to minimise the loss and inconvenience resulting from the above

measures, and that they will mutually support one another in resisting any special measures aimed at one of their

number by the covenant breaking State, and that they will take the necessary steps to afford passage through their

territory to the forces of any of the Members of the League which are co-operating to protect the covenants of the

League.

Any Member of the League which has violated any covenant of the League

may be declared to be no longer a Member of the League by a vote of the Council

concurred in by the Representatives of all the other Members of the League

represented thereon.

ARTICLE 17.

n the event of a dispute between a Member of the League and a State which is

not a Member of the League, or between States not Members of the League, the

State or States, not Members of the League shall be invited to accept the

obligations of membership in the League for the purposes of such dispute, upon

such conditions as the Council may deem just. If such invitation is accepted,

the provisions of Articles 12 to 16 inclusive shall be applied with such

modifications as may be deemed necessary by the Council.

Upon such invitation being given the Council shall immediately institute an inquiry into the circumstances of the

dispute and recommend such action as may seem best and most effectual in the circumstances.

If a State so invited shall refuse to accept the obligations of membership in the League for the purposes of such dispute,

and shall resort to war against a Member of the League, the provisions of Article 16 shall be applicable as against the

State taking such action.

If both parties to the dispute when so invited refuse to accept the obligations of membership in the League for the

purpose of such dispute, the Council may take such measures and make such recommendations as will prevent

hostilities and will result in the settlement of the dispute.

ARTICLE 18.

Every treaty or international engagement entered into hereafter by any Member of

the League shall be forthwith registered with the Secretariat and shall as soon

as possible be published by it. No such treaty or international engagement shall

be binding until so registered.

ARTICLE 19.

The Assembly may from time to time advise the reconsideration by Members of the

League of treaties which have become inapplicable and the consideration of

international conditions whose continuance might endanger the peace of the

world.

ARTICLE 20.

The Members of the League severally agree that this Covenant is accepted as

abrogating all obligations or understandings inter se which are inconsistent

with the terms thereof, and solemnly undertake that they will not hereafter

enter into any engagements inconsistent with the terms thereof.

In case any Member of the League shall, before becoming a Member of the League, have undertaken any obligations

inconsistent with the terms of this Covenant, it

shall be the duty of such Member to take immediate steps to procure its release

from such obligations.

ARTICLE 21

Nothing in this Covenant shall be deemed to affect the validity of international

engagements, such as treaties of arbitration or regional understandings like the

Monroe doctrine, for securing the maintenance of peace.

ARTICLE 22.

To those colonies and territories which as a consequence of the late war have

ceased to be under the sovereignty of the States which formerly governed them

and which are inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the

strenuous conditions of the modern world, there should be applied the principle

that the well-being and development of such peoples form a sacred trust of

civilisation and that securities for the performance of this trust should be

embodied in this Covenant.

The best method of giving practical effect to this principle is that the tutelage of such peoples should be entrusted to

advanced nations who by reason of their resources, their experience or their geographical position can best undertake

this responsibility, and who are willing to accept it, and that this tutelage should be exercised by them as Mandatories

on behalf of the League.

The character of the mandate must differ according to the stage of the development of the people, the geographical

situation of the territory,

its economic conditions, and other similar circumstances.

Certain communities formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire have reached a stage of development where their

existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognised subject to the rendering of administrative advice and

assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone. The wishes of these communities must be a

principal consideration in the selection of the Mandatory.

Other peoples, especially those of Central Africa, are at such a stage that the

Mandatory must be responsible for the administration of the territory under conditions which will guarantee freedom of

conscience and religion, subject only

to the maintenance of public order and morals, the prohibition of abuses such as

the slave trade, the arms traffic, and the liquor traffic, and the prevention of

the establishment of fortifications or military and naval bases and of military

training of the natives for other than police purposes and the defence of

territory, and will also secure equal opportunities for the trade and commerce

of other Members of the League.

There are territories, such as South-West Africa and certain of the South Pacific Islands, which, owing to the sparseness

of their population, or their small size, or their remoteness from the centres of civilisation, or their geographical

contiguity to the territory of the Mandatory, and other circumstances, can be best administered under the laws of the

Mandatory as integral portions of its territory, subject to the safeguards above mentioned in the interests of the

indigenous population.

In every case of mandate, the Mandatory shall render to the Council an annual report in reference to the territory

committed to its charge.

The degree of authority, control, or administration to be exercised by the Mandatory shall, if not previously agreed

upon by the Members of the League, be explicitly defined in each case by the Council.

A permanent Commission shall be constituted to receive and examine the

annual reports of the Mandatories and to advise the Council on all matters

relating to the observance of the mandates.

ARTICLE 23.

Subject to and in accordance with the provisions of international conventions

existing or hereafter to be agreed upon, the Members of the League:

(a) will endeavour to secure and maintain fair and humane conditions of labour for men, women, and children, both in

their own countries and in all countries to which their commercial and industrial relations extend, and for that

purpose will establish and maintain the necessary international organisations;

(b) undertake to secure just treatment of the native inhabitants of territories under their control;

(c) will entrust the League with the general supervision over the execution of agreements with regard to the traffic in

women and children, and the traffic in opium and other dangerous drugs;

(d) will entrust the League with the general supervision of the trade in arms and ammunition with the countries in

which the control of this traffic is necessary in the common interest;

(e) will make provision to secure and maintain freedom of communications and of transit and equitable treatment for

the commerce of all Members of the League. In this connection, the special necessities of the regions devastated

during the war of 1914-1918 shall be borne in mind;

(f) will endeavour to take steps in matters of international concern for the prevention and control of disease.

ARTICLE 24.

There shall be placed under the direction of the League all international

bureaux already established by general treaties if the parties to such treaties

consent. All such international bureaux and all commissions for the regulation

of matters of international interest hereafter constituted shall be placed under

the direction of the League.

In all matters of international interest which are regulated by general conventions but which are not placed under the

control of international bureaux or commissions, the Secretariat of the League shall, subject to the consent of the

Council and if desired by the parties, collect and distribute all relevant information and shall render any other assistance

which may be necessary or desirable.

The Council may include as part of the expenses of the Secretariat the expenses of any bureau or commission which is

placed under the direction of the League.

ARTICLE 25.

The Members of the League agree to encourage and promote the establishment and

co-operation of duly authorised voluntary national Red Cross organisations

having as purposes the improvement of health, the prevention of disease, and the

mitigation of suffering throughout the world.

ARTICLE 26.

Amendments to this Covenant will take effect when ratified by the Members of the

League whose representatives compose the Council and by a majority of the Members of the League whose

Representatives compose the Assembly.

No such amendment shall bind any Member of the League which signifies its dissent therefrom, but in that case it shall

cease to be a Member of the League.”

(Quoted from FoundingDocs.gov.au).