United Nations Security Council on the United Nations Headquarters in New York City, Neptuul, CC 3.0

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council is often seen as the most important and most powerful entity within the United Nations. This organ is comprised of fifteen member states, 5 of which have permanent seats, and a UN veto power. These states are the United States, the UK, Russia, China, and France. The other ten seats are non-permanent seats (two year terms), and these seats do not have a veto power in the United Nations. These ten non-permanent members of the UN Security Council are selected by the UN General Assembly, and are often based on region (for 2016-2017), the other non-permanent members of the UN Security Council are: Angola, Egypt, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Senegal, Spain, Ukraine, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

In this article, we shall discuss the history of the United Nations Security Council, the functions of the United Nations Security Council in international relations, the powers of the UNSC, the makeup of the United Nations Security Council, criticisms of the makeup of the Security Council, the relationship to the United Nations General Assembly, as well as the various discussions and proposed ideas to reform the United Nations Security Council.

History of the United Nations Security Council

To understand the context of the current makeup of the United Nations Security Council, it is important to know the history of the United Nations Security Council, with particular attention to the formation and evolution of the United Nations within the context of the Security Council (follow the link for a history of the United Nations). The United Nations came about following the events of World War II. The international states were concerned about international security, and thus, formed an organization that would help ensure that the world was a peace-filled one, and where, if a state acted as an aggressor, that other states, through the United Nations, would cooperate together and prevent said state from destabilizing the international system. And in this desire, they formed the United Nations Security Council, which they saw as having the “primary responsibility” for this international security (Butler, 2012). And in Article 25 of the United Nations Charter, any state who joined gave the Security Council this power (Butler, 2012). And as Butler (2012) explains, “[w]hile this language [of Article 25] is simple, its weight cannot be exaggerated. The Security Council is the only organ of the U.N. whose decisions are binding upon all members. The Security Council’s decisions have the authority of law” (27).

Many may wonder why the various states who were a part of the United Nations would agree to a UN Security Council where a handful of states had UN veto power. At the time, these five states, the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union, China, and France were seen as the “victors” of the war, and thus, many of them were highly active in forming the United Nations as an organization, as well as negotiating the mandate of the United Nations through the writing of the UN Charter. Many states did object to this idea of permanent veto powers in the UN Security Council, however, the military powers not only kept pressing the issue, but they often put it in a way that without UN veto power, the organization would not exist (Butler, 2012). For example, The a US representative said that without UN veto power, the United Nations Charter would not exist. The British representative was quoted in the early UN meeting documents as saying that

“The present voting provisions were in the interest of all states and not merely of the permanent members of the Security Council. Peace must rest on the unanimity of the great powers for without it whatever was built would be built upon shifting sands, or no more value than the paper upon which it was written. The unanimity of the great powers was a hard fact, but an inescapable one. The veto power was a means of preserving that unanimity, and far from being a menace to the small powers, it was their essential safeguard. Without that unanimity all countries, large and small, would fall victims to the establishment of gigantic rival blocs which might clash in some future Armageddon. Cooperation among the great powers was the only escape from this peril; nothing was of comparable importance” (Butler, 2012: 29).

Despite what some think regarding the early actors’ intentions to provide equality for all states in the United Nations through a “balance” of membership (Article 23 of the UN Charter), others point out that “this is a distorted picture, however, because the founders were not concerned about “balancing” such matters. Indeed, their emphasis on performance, on credibility in threatening Chapter VII enforcement measures, and on the unity of the great powers was so pronounced that at the San Francisco founding conference they did not hesitate to bully or dismiss delegations with other ideas” (Luck, 2005b: 135-136). The US, UK, and Russia, and then France and China, were not interested in hearing other opinions, but rather wanted states to go along with the plans they drafted ahead of time in their own conferences. Luck (2005b) goes on to say that “[o]n various occasions in San Francisco, representatives of the Big-Three made it known that they would prefer no world body to one with equitable but feckless properties of the League of Nations” (136). Furthermore, they wanted to ensure that any change to the United Nations would not be easy to accomplish (Luck, 2003).

However, the concern by many, which will be discussed later, is the idea that the United Nations veto power states now see this “responsibility” that they used to argue for the veto power is now viewed by them “as a right” (Butler, 2012: 31), and that this has led to further imbalance of power within the UNSC compared to the UNGA, as well as the use of this initiation formation in the United Nations Security Council for the P5 states to carry out actions that are clearly related to their national interests, even if as the cost of ensuring human rights are protected equally.

At United Nations Security Council, Warren Austin, U.S. delegate, holds Russian-made sub-machine gun dated 1950, captured by American troops in July, 1950. He charges that Russia is delivering arms to North Koreans. Lake Success, New York, September 18, 1951. International News Photos. Public Domain

As we shall discuss later, one suggestion is to expand the number of members in the United Nations Security Council. This has only happened once, where in 1963, the UNSC agreed to increase the non-permanent members to ten, from the previous six non UN veto members (Ronzitti, 2010: 4).

Functions of the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council is most known for its ability to act against state that disrupt international peace and security. The United Nations Charter offers a number of places where states are explicitly told not to be an aggressor, and also provide support for the UNSC to act against a state aggressor is supported. With regards to overall security of the international system, one of the first references to the ability of the United Nations Security Council to respond to a aggressor state is found in Article 2, paragraph 4 of the United Nations Charter, where it states that “all states shall refrain from the threat or use of force in their international relations” (Weiss, Forsythe, Coate, & Pease, 2014: 32-33).

In fact, there are actually four places where the United Nations Security Council can use a veto. There is a UN veto “… over the adoption by the Security Council of any substantive and binding decisions pursuant to Article. This is the first of the Security Council’s vetoes. The others include a veto over the recommendation to the General Assembly of a person to be appointed Secretary-General of the U.N.; a veto over applications for membership of the U.N., and possibly, and perhaps crucially, a veto over any amendment to the Charter” (Butler, 2012: 29) (The selection of the UN Secretary General “is appointed in a two stage process. A candidate is first recommended by the Security Council, and then must be approved by the 193-member General Assembly…In every ballot [where more than one candidate is put forward], the 15 Security Council members [assess] each candidate by voting either “encourage,” “discourage” or “no opinion” (Hume, 2016).

Thus, the actual UN veto carries significant power. But as we can imagine, even the threat of one is a great political tool for these five permanent members, and the threat of a veto in private is actually common (Butler, 2012).

Within the United Nations Security Council meetings, the members discuss various international relations issues. The Security Council also decides what issues to hear, and who can be present at the meetings; they are able to invite others states or delegations. However, it was in 1992 that Diego Arria, an ambassador from Venezuala met with a priest from Bosnia, who told him about the crimes being committed by the Yugoslavian military in the Balkans. Arria, not given a chance to speak to the entire United Nations Security Council, did begin to hold an informal briefing session. It was following this event that now “enables a member of the Council to invite other Council members to an informal meeting, held outside of the Council chambers, and chaired by the inviting member. The meeting is called for the purpose of a briefing given by one or more persons, considered as expert in a matter of concern to the Council” (Mertus, 2010: 117).

The United Nations Security Council and Human Rights

The United Nations Security Council is one of the key organs within the United Nations with regards to the power of protecting human rights in the international system. However, the United Nations Security Council is unique within the United Nations organs in that its initial mandate was with regards to international peace and international security, and not human rights (Mertus, 2010). As Professor Julie Mertus (2010), in her book The United Nations and Human Rights: A Guide for a New Era explains,

“While other UN organs such as the General Assembly and the Economic and Social Council were expressly empowered in their original mandates to deal with human rights and fundamental freedoms, the Security Council was not. Rather, the Security Council was left free to interpret what it meant to promote international peace and security. In the early years and throughout much of the Cold War, the Security Council sought to isolate itself from human rights concerns and to close its decision-making processes to non-governmental organizations that might push human rights and humanitarian matters into international attention. The Security Council did its best to sidestep the few human rights issues that fell under its purview” (99).

It was not long however when the United Nations Security Council took an increased role with regards to international human rights. This was particularly the case because of the intersection between human rights and international security. Human rights actions before a conflict could help avoid such a situation that would potentially destabilize international peace and security. And during a conflict, giving attention to human rights could help bring an end to a war. And following war, ensuring human rights were protected could help hold those who committed human rights abuses accountable for their actions (Mertus, 2010).

The United Nations Security Council has the mandate to protect human rights in international relations and international affairs. There are a number of ways that the United Nations Security Council can argue for action with regards to human rights. To begin, their key responsibility has been to ensure international peace and security. Thus, if a human rights violation is being committed, and it affects international security, the UNSC, through the United Nations Charter, can act, through sanctions, military actions, etc… (Mertus, 2010). Moreover, as Mertus (2010) explains, “[i]n discharging its duties, the Security Council is to act on behalf of the membership “in accordance with the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations.” The purposes and principles of the United Nations Charter, as delineated in the Charter itself, include not only the maintenance of international peace and security, but also “respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples,” and “promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all”” (99-100).

Julie Mertus (2010) explains that the United Nations Security Council has both coercive and non-coercive means to ensure human rights. The UNSC can itself pass resolutions. And while “technically non-binding, resolutions made under the Council’s Chapter VI powers have a certain value through setting precedents as multilateral statements on human rights” (102). But along with UNSC resolutions, they can also assign peacekeepers to various civil and international conflict areas. With regards to United Nations peacekeepers, “[t]he traditional tasks of these operations included monitoring and enforcing ceasefires; observing frontier lines; and keeping conflicting parties separate” (104). However, with the rise of UN peacekeeping missions, we have also seen an increase in the types of actions that they carry out. For example, now, peacekeepers are often engaged with monitoring elections, safeguarding individuals, as well as helping with humanitarian aid, reporting of rights abuses, as well as helping with “the reconstruction of government or police functions” (Mertus, 2010: 104).

Part of the reason that human rights became a more central focus of the United Nations and the United Nations Security Council is because of the leadership and initiatives of the various Secretary-Generals of the UN. For example, In 1991, then Secretary-General Pérez de Cuéllar highlighted what he thought was the ineffectiveness of the United Nations General Assembly with regards to human rights, going as far as to call states “callous” (Mertus, 2010: 100). Other Secretary-Generals followed suit with regards to their advocacy of human rights. For example, Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali, following his appointment in 1992, emphasized the importance of the United Nations to adopt greater involvement in peacekeeping, as did Secretary-General Kofi Annan (Mertus, 2010). In fact, “[i]n 1999, the Secretary-General [Annan] electrified and angered much of the UN General Assembly by highlighting the inconsistencies in the international response to humanitarian emergencies and articulating a powerful moral imperative to “do something.” In what has come to be known as the “Annan Doctrine,” he repeatedly stated that state sovereignty must not shield states in the face of crimes against humanity” (Mertus, 2010: 102). Thus, such actions had a role in the United Nations Security Council adopting additional actions with regards to human rights (Mertus, 2010).

But the United Nations Security also has coercive means to protect human rights. The most notable power is granted with Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, which allows the Security Council to use sanctions, as well as a military response. It also allows other states to join the Security Council actions, although it is not mandatory that they do so (Mertus, 2010). But despite the ability to protect human rights with military and economic actions, there have indeed been many criticisms of the United Nations Security Council’s actions (or the lack thereof) with regards to actually using Chapter VII for human rights violations that have taken place in different parts of the world (Mertus, 2010).

Criticisms of the United Nations Security Council

There are a number of criticisms of the United Nations Security Council. Scholars break down the criticisms in three categories: namely, equity, or the lack thereof the UNSC in relation to the UNGA state powers, effectiveness in their actions, as well as prerogatives or “insider concerns that do not fit well with charges of ineffectiveness and that do not have much resonance beyond Turtle Bay [in New York City, where the UN is located]” (Luck, 2005b: 129).

One of the biggest criticisms of the United Nations Security Council is in relation to the power that it has compared to the United Nations General Assembly. And because of this power imbalance, many have argued that the General Assembly be granted additional authority (CFR, 2014).

For example, a primary complaint of the UNSC has been the structure of the Security Council with regards to states represented, as well as the UNSC veto power for the five permanent members. With regards to overall representation, again, the United Nations Security Council has 15 members, ten of them elected for two year terms. Thus, among the biggest criticisms is what may see as this unfair balance of power between the five permanent member states, and the rest of the world, not only those who never or rarely get to serve on the United Nations Security Council, but even those that do serve, as their weight on the SC pales in comparison to the permanent veto power member states. And herein lies the big problem that plagues the organization and what it is supposed to stand for, for as Butler (2012) explains, “[t]he Charter provides a contradicting set of circumstances. On the one hand, there is a notion of egalitarianism among the member states, common purpose and commitment, and the accompanying notion that this political commitment will be supported by a truly objective, fair, and capable bureaucracy. On the other hand, in the midst of this extraordinary set of circumstances, a group with astonishing privileges is established, and specifically enabled to play an all-pervasive and dominant role — the Permanent Five” (25).

However, states in the General Assembly have put forward resolutions calling for an advisory group that could help move discussions with regards to ways in which the UNSC can be altered towards a “more representative membership that reflected geopolitical realities and prepared the body to fulfill its mandate of maintaining global peace and security” (UN, 2013).

For example, during the opening of the 69 Session of the United Nations General Assembly, Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez said that “The United Nations requires a profound reform and the defence of its principles. The Secretary-General should be an advocator and guarantor of international peace and security…”. He went on to also say that “The Security Council should be rebuilt upon democracy, transparency, a fair representation of the countries of the South that are discriminated against among Permanent and Non-Permanent Members, credibility, strict observance of the United Nations Charter, without double standards, obscure procedures or the anachronistic veto”” (UN, 2014). And related to Security Council reform, Indian leader Narendra Modi also spoke about the importance of reforming the United Nations Security Council, calling for the United Nations become more “participative” in nature (BBC, 2014). As the article states, India has called for having a “permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council” (BBC, 2014), something other states have also called for. Others such as United Nations President Sam Kahamba Kutesa held a similar position, when he was quoted as saying that “One of the priorities I highlighted for this session is continued focus on the revitalisation of the General Assembly and the reform of the Security Council. While some progress towards making the General Assembly more effective and efficient has been made, we need to do more” (The Economic Times, 2014).

But again, some are also critical of the UN and the hyprocratic positions leaders take compared to what the U.N. stands for for this reason: an organization that is supposed to defend the human rights of all beings elected an individual (Kutesa) who has strongly opposed same-sex rights in Uganda (Lowder, 2014). And while the position does not carry much power, “[c]ritics of the choice, including many LGBTQ and human rights activists, are concerned that honoring Kutesa and, by extension, Uganada in such a way will send the wrong message with regard to the country’s recently imposed anti-gay legislation.Critics of the choice, including many LGBTQ and human rights activists, are concerned that honoring Kutesa and, by extension, Uganada in such a way will send the wrong message with regard to the country’s recently imposed anti-gay legislation” (Lowder, 2014).

Other still argue that the Security Council often ignores its responsibilities to other UN entities such as the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (Luck, 2005b). Related to this, other organs with the United Nations have felt that they do not have the adequate support to carry out actions and mandates (Luck, 2005), something that continues to be a criticism of the United Nations and its overall effectiveness as an international organization. Related to this, some have also made criticisms saying that compared to their states, the P5 members actually contribute relatively little to the military and finances of United Nations actions (Luck, 2005b: 130).

The United Nations Security Council Veto Power

One of the other major criticisms of the United Nations Security Council is in relation to the notion of the veto power that the five permanent UNSC countries (US, UK, China, Russia, & France) have, as well as the way they have used the UN veto power in the past. Many view the veto power as simply a way for these states to do what they want in the international system. As Butler (2012) explains,

“The Permanent Five have behaved and continue to behave in ways that suggest that they see the power that they hold as rightful and free, to be exercised by them in whatever manner they choose. The notion that this power was given to them, over strenuous objections, but for the reason of the good that it might do in preserving the peace, has been substantially replaced by the idea that they have a power that they can use to protect and extend their own individual national interests. This selfish outlook is often not consistent with the purposes and principles of the Charter” (31). In fact, many of the veto powers used by countries have been quite political; this is evident when looking at vetoes during the Cold War, with the U.S. and the USSR both vetoing actions that they did not see benefiting them (Butler, 2012).

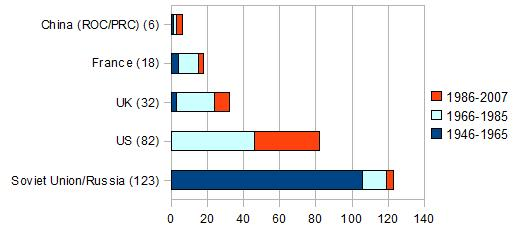

Number of resolutions vetoed by each of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council between 1946 and 2007. (Source: globalpolicy.org, Polemarchus. Public Domain

Another related criticism is that these five powers often dictate what the UNSC discusses, and based on their interests, they often spend more attention on issues that are of more concern to these members. Some have wondered whether the UNSC looks at all issues of security fairly (Butler, 2012), or how it looks that the United Nations members have went to war without UN authorization, such as in the case of Iraq (Meta, 2008), where there was worldwide protests against the Bush administration’s decision to invade in 2003.

United Nations Security Council Failures to Protect Human Rights

Related to the issue of person interest has been the unfortunate reality that the veto power states in the United Nations Security Council has either threatened a veto, or used a veto when they wanted to protect their own interests, even if it was at the expense of protecting human rights or international security. There are a number of cases that would fall within this category. One could point to a host of issue, whether it is United States vetoes regarding criticisms against Israel (Mehta, 2008), whether it is Russia with regards to its relationship with the Federal Republics of Yugoslavia (today Russia’s ally Serbia), or China’s ties with the Omar al-Bashir regime in Sudan (Meta, 2008), and thus its reluctance to put more pressure on him while the Sudanese government backed the Janjaweed, who carried out genocide in the Darfur region of Sudan. Even today, one saw the issue of self-interest play out with Russia and China using a veto when the United Nations Security Council wanted to refer Syria to the International Criminal Court (Black, 2014) (In fact, on October 13th, 2014, New Zealand criticized the United Nations Security Council for its lack of actions on issues in Iraq, Syria, and the Ukraine (Su, 2014)). Or, even when the United Nations has acted for human rights, some argue that the actions have often been inconsistent, leading to more criticisms as it relates to P5 interests in certain conflicts or situations, as opposed to others (Luck, 2005b). And often times, it has been argued that states could have helped stop human rights abuses if they were to have provided resources to support international efforts (Voeten, 2007).

Current United Nations Security Council Veto Members

![U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry meets with P5 members at the United Nations in New York City on September 25, 2013. [State Department photo/ Public Domain]](http://internationalrelations.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Secretary_Kerry_Meets_With_P5_Members_9942826116_cropped.jpg)

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry meets with P5 members at the United Nations in New York City on September 25, 2013. [State Department photo/ Public Domain]

United Nations Security Council Reform

Because of the criticisms of the United Nations Security Council noted above, individuals outside of the UN, and even within the United Nations have been calling for reforming the United Nations Security Council. Part of the reason has to do with what is seen as an imbalance of power among the P5 members, whereas other arguments center on the notion that the permanent members of the UN Security Council do not accurately reflect current conditions of world power. Namely, some of the countries who are permanent members are not the superpowers that they once were. As Smallman & Brown (2015) write: “At the end of World War II, there were five Great Powers, which dominated international affairs. Few scholars or diplomats foresaw that the Age of Empire had ended and that in the space of roughly two decades, both Great Britain and France would lose their empires. Both nations underwent a relative economic decline. They remained wealthy states but were no longer central to global affairs” (76).

Thus have seen a host of suggestions, as well as panels and conferences on United Nations reform (Yale Center for the Study of Globalization, 2005), and attempts by various UN Secretary-Generals for reform (Luck, 2005a; 2005b). For example, “[t]he question of Security Council reform and enlargement has been actively discussed within the U.N. General Assembly since 1993, when it established an “Open-ended Working Group to consider all aspects of the question of increase in the membership of the Security Council, and other matters related to the Security Council” (Blanchfield, 2011: 2). And even before the working group, one could point to UN reforms in the 1980s, during the tenure of Boutros Boutros-Ghali, as well as under Kofi Annan in the 1990s and 2000s. There were also key efforts in 2005 with the U.N. World Summit, where there were calls for improvement on human rights issues, on emergency response, on the Security Council, whistleblower protections, improvement upon overall coordination regarding the United Nations, along with other issues. (Blanchfield, 2011).

In fact, when looking at the history of the United Nations, it becomes evident that reforming the United Nations has been an almost regular part of the organization. The states get together, often after leaders speak out against the structures of the UN, in attempts to carry out a wide range of United Nations reforms. Often, a commission is put together. Then, after the leaders discuss the reforms that they would like to carry out, the Secretary General of the United Nations attempts to share their ideas to the entire General Assembly membership. Then, after this, the entire UNGA will discuss these points. Then, following this, there is usually an event (often at the time of a commemoration of sorts) where they will call for the approval of these new UN reform issues. Then, finally, as Luck (2005a) points out, “state leaders and the secretariat always seem to find reasons to paint even incremental reforms in glowing colors—in part for public relations and in part because their expectations tend to be pitched much lower than their rhetoric. These claims are traditionally coupled with declarations about unfinished work and renewed dedication.These assertions, along with independent commentary about the glaring gaps between the standards voiced in stages one and five, provide an impetus for the next round of UN reform. As it slowly gains momentum, all of the reform steps that could not be agreed in time for the megaevent still need to be addressed. Indeed, such culminating events mark beginnings as much as endings in the ongoing reform process” (408-409). However, as is the case, there is rarely these deep reforms that are demanded by UNGA state leaders.

Yet, despite any improvements and additional calls for reforms with regards to the United Nations and the United Nations Security Council, there are a number of more specific suggestions that have been made in the literature and by different international actors with regards to more drastic United Nations Security Council reform.

Adding Veto Power Members to the United Nations Security Council

One UN Security Council reform advocated by those looking to alter existing power structure in the organization has to do with the UN Security Council veto power. Given the distribution of power towards a handful of states, a potential remedy to the power imbalances of the United Nations Security Council permanent veto power members is the idea of additional additional veto member states to the UNSC. While this would be a major UN Security Council reform, many have been critical of this position. For one, who will get the additional veto power seats? In addition, how would this effect the United Nations Security Council, or how would it improve upon the criticisms that currently face the UNSC. Namely, some already believe that the five veto powers have led to self-interest and inefficiency. The idea of adding more would not help matters (Russett, 2005). It has been noted that “The existing members have mixed feelings [about more permanent members]. The UK and France say they are in favour; the US and Russia are more tepid, warning a big council could be less effective. And China is dead against it. And there are also jealous regional rivals who don’t want to see their neighbours succeed. But big candidate countries such as Brazil, India, Germany, Japan and South Africa say there is no realistic alternative” (The Guardian, 2015).

Furthermore, the states currently having veto power would not approve of this new development, since it would weaken their own power in the United Nations Security Council; it would make passing any action even more difficult (Russett, 2005). Furthermore, these states don’t know what the future looks like, and thus, may be highly reluctant to give up power, even when they are currently some of the strongest militaries and economies in the world. As Keating (2011) explains, “[t]here is also a growing recognition that in politics and economics, nothing is permanent and it is therefore danger sin the security context to pretend that states will always continue to be the same in relative terms — or even to east at all” (as in the case of Yugoslavia, for example) (1).

Also, arguably one of the most controversial positions within this UN Security Council reform would be the call for the United States to give up the veto power that it currently has. Not only does not US no longer need Article 42 and the veto power to ensure its security, but also that the US, by giving up the veto, would lead other states to also give up their veto power (39). However, some, writing earlier, pointed out that because of the unlikelihood of states giving up the power, instead, they have hoped that the P-5 states will have “voluntary restraint on the veto use” (Mehta, 2008: 6) (since it would take the P5 to sign off on any UN Charter changes, and then it would have to pass through the UNGA by 2/3 majority (Russett, 2005)) (some states such as a number of African states have called for removing the veto power in the United Nations Security Council (Ronzitti, 2010)) (However, many argue that change is needed, in that the P-5 cannot use their veto for their own interests, and their interests are not more pressing than those of the rest of the United Nations members (Mehta, 2008).

Ten Non-Permanent United Nations Security Council Seats

Another UN Security Council reform idea looks at the total number of members in the UNSC. One of the primary criticisms of the United Nations Security Council has been the ten non-permanent member seats. This idea about expanding the overall membership of the United Nations Security Council was raised in 1979, although it wasn’t until 1993 that the issue was given renewed attention in the UNGA (Mertus, 2010). Given the world’s population and states in the world, some have suggested that there may indeed be a bias in favor of Western states, since they have three permanent members (the US, UK, and France), along with two additional non-permanent member slots (Butler, 2012). In fact, this imbalance was apparent to many as early as the 1950s and 1960s with the increase in United Nations member states from Africa and Asia (Luck, 2003). Thus, due to these imbalances, some have suggested having the US stay on, along with only one European Union position instead of keeping both the UK and France (Butler, 2012: 34). And because of the number of states, some have wondered whether the current regional allocations should be re-examined to better reflect populations within the regions (Butler, 2012) as many think there is an imbalance (Trachsler, 2010) (even US ambassador to the UN Samantha Power admitted that the current model leaves out a number of states, and does not represent the world’s population accurately (Inderfurth, 2013)). When looking at regional representation, as of right now, Africa and Asia have five seats, Eastern Europe has one, Latin America and the Caribbean has two seats on the UNSC, and Western Europe and Others also have two seats.

There have been a number of suggestions on how to improve the current distribution of United Nations Security Council Seats. For example, one possibility is the idea of adding additional seats from the different regions of the world, despite some thinking this would do little to improve the effectiveness of the UNSC (Weiss, 2003). Other ideas include providing certain rising economic states (such as addressing Germany or Japan’s power (Meta, 2008), or regional powers such as Brazil in South America, or India a permanent non-veto power seat on the United Nations Security Council. However, a challenge with this would be to add states in a way that would not upset other countries in the respective regions. Russett (2005) explains how states might respond to discussions of new permanent membership on the United Nations Security Council, given the international relations realities of the international system, when he says: “Pakistan and China have adamantly opposed any package that would give India a permanent seat; Mexico and especially Argentina have made it clear that they would not permit a permanent seat for Brazil; Japan was opposed by China and others in East Asia with long memories” (157). He goes on to say that “[e]ven closely integrated allies could be opposed: Italy conducted an extended and vigorous campaign against Germany, partly as a result of long memories and partly because a German permanent seat would reduce the chances for Italy even to have frequent access to a non-permanent one. If Nigeria in Africa, what about Egypt and South Africa?” (Russett, 2005: 157). The issue is not only that they want the seat, but if they don’t get it, those states may “see new permanent Security Council members as permanently chaining the power relativities in their region to their disadvantage” (Keating, 2011: 1). Yet despite these concerns, there have still been attempts to propose new restructuring formations. For example, various blocks and international organizations have called for UN Security Council reform, and have lobbied for additional seats, whether it is based on region, religion, etc… (Ronzitti, 2010).

In addition, Richard Butler (2012) outlines yet another United Nations Security Council reform system which would have nine regions, instead of the four set today. He goes on to explain that “[e]ach electoral region would be able to designate a “Permanent Member.” The identity of that permanent member could itself change. For example, the permanent member from the Latin American and Caribbean group for three years could be Brazil. Following agreement within the regional group, the subsequent three years 2012 could see that same seat occupied by Argentina. The nine permanent members would each have a veto defined as follows: for the adoption of any proposition at least seven of them would have to vote in the affirmative. In other words, a proposition could be vetoed if three of them agreed to vote in the negative” (37-38). He also suggests reforming the seats per region, where Western Europe would have two seats, Eastern Europe one seat, Mediterranean Africa and Arabia one seat, South Africa two seats, Central and South Asia two seats, North Asia one seat, Southeast Asia and the Pacific three seats, North America one seat, and Latin America and the Caribbean 3 seats (38). The current Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has also advocated UN Security Council Enlargement (Blanchfield, 2011).

Another idea for reforming the United Nations Security Council is what has been referred to the “20/20 proposal.” this proposal “would run for 20 years and would give special status to 20 key stakeholder states, who would have the opportunity on average, and subject to being elected, to serve for two years on the Security Council every four years” (3). Keating (2011) argues that this would benefit “emerging states” (3). Lastly, seeing the baseness of military action within the Security Council, some have also called to “[c]hange the way in which the SC orders military action in order to control the process” (Mehta, 2008: 4).

United Nations Security Council Books

Edward C. Luck, UN Security Council: Practice and Promise

David Bosco, To Rule Them All: The UN Security Council and the Making of the Modern World.

References

BBC (2014). India’s Modi Calls For Reform In Speech To UN. BBC, 27 September 2014. Available Online: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-29373722

Black, I. (2014). Russia and China Veto UN Move to Refer Syria to International Criminal Court. The Guardian, Thursday 22 May, 2014. Available Online: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/22/russia-china-veto-un-draft-resolution-refer-syria-international-criminal-court

Blanchfield, L. (2011). United Nations Reform: U.S. Policy and International Perspectives. Congressional Research Service, December 21, 2011, pages 1-30. Available Online: http://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL33848.pdf

Butler, R. (2012) Reform of the United Nations. Penn State Journal of Law & International Affairs, Vol. 1, Issue 1, pages 23-39.

Economic Times (2014). UN Security Council Reform Among Priorities of 69th General Assembly Session. September 17, 2014. Available Online: http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-09-17/news/54024772_1_unsc-poverty-and-hunger-session

Gowan, R. & Gowan, N. (2014). Pathways to Security Council Reform. May 2014, pages 1-35. Available Online: http://csnu.itamaraty.gov.br/images/pathways_sc_reform_final.pdf

Hume, T. (2016). Portugal’s Antonio Guterres poised to become next UN secretary-general. http://www.cnn.com/2016/10/05/world/un-secretary-general-antonio-guterres/

Inderfurth, K.F. (2013). The U.N.’s Rubik’s Cube:’ Security Council Reform, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Vol. 3, No. 8, August, 2013, pages 1-3. Available Online: http://csis.org/files/publication/FINAL%20August%202013_WadhwaniChair_USIndiaInsight.pdf

Keating, C. (2011). Stalled UN Security Council Reform: Time to Consider Resetting Policy? Institute for Security Studies Policy Brief No. 29, December, pages 1-4. Available Online: http://www.issafrica.org/uploads/PolBrief29.pdf

Lowder, J.B. (2014). Sam Kutesa, Ardent Supporter of Uganda’s Anti-Gay Law, Elected President of U.N. General Assembly. Slate, http://www.slate.com/blogs/outward/2014/06/12/sam_kutesa_ardent_supporter_of_uganda_s_anti_gay_law_elected_president_of.html

Luck, E.C. (2003). Reforming the United Nations: Lessons from a History in Progress. International Relations Studies and the United Nations Occasional Papers, No. 1, pages 1-74. Available Online: http://www.peacepalacelibrary.nl/ebooks/files/373430132.pdf

Luck, E.C. (2005a). How Not to Reform the United Nations. Global Governance, Vol. 11, pages 407-414. Available Online: http://faculty.maxwell.syr.edu/hpschmitz/PSC124/PSC124Readings/LuckUnitedNationsReform.pdf

Luck, E.C. (2005b). Rediscovering the Security Council: The High-Level Panel and Beyond. Chapter 4, pages 126-152, in Yale Study for the Center of Globalization (2005). Reforming the United Nations for Peace and Security. March 2005, pages 1-196. Available Online: http://www.ycsg.yale.edu/core/forms/Reforming_un.pdf

Mehta, V. (2008). Reforming the UN for the 21st Century, pages 1-8. Available Online: http://unitingforpeace.com/resources/speeches/Reforming%20the%20UN.pdf

Mertus, J. (2009). The United Nations and Human Rights: A Guide for a New Era. New York, New York. Routledge.

Ronzitti, N. (2010). The Reform of the UN Security Council. Instituto Affari Internazionali, Documenti IAI 10 13, July 2010, pages 1-20. Available Online: http://www.iai.it/pdf/dociai/iai1013.pdf

Russett, B. (2005). Security Council Expansion: Can’t, and Shouldn’t. Chapter 5, pages 153-166, in Yale Study for the Center of Globalization (2005). Reforming the United Nations for Peace and Security. March 2005, pages 1-196. Available Online: http://www.ycsg.yale.edu/core/forms/Reforming_un.pdf

Smallman, S. & Brown, K. (2015). Introduction to International and Global Studies, Second Edition. Chapel Hill, North Carolina. University of North Carolina Press.

Su, R. (2014). New Zealand Slams ‘Paralysis’ Of UN Security Council On ISIS And Ukraine Conflict. International Business Times. October 13th, 2014. Available Online: http://au.ibtimes.com/articles/569394/20141013/new-zealand-united-nations-isis-security-council.htm#.VD1DiksyAdu

Talmon, S. (2005). The Security Council as World Legislature, The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 99, No. 175, pages175-193.

The Guardian (2015). Vetoed! What’s wrong with the UN security council – and how it could do better. The Guardian. 23 September 2015. Available Online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2015/sep/23/un-security-council-failing-70-years

Trachsler, D. (2010). UN Security Council Reform: A Gordian Knot? CSS Analysis in Security Policy, No. 72, pages 1-3. Available Online: http://www.css.ethz.ch/publications/pdfs/CSS-Analyses-72.pdf

United Nations (2013). General Assembly GA/11450 Calling for Security Council Reform, General Assembly President Proposes Advisory Group to Move Process Forward. 7 November 2013. Available Online: http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2013/ga11450.doc.htm

United Nations (2014). Cuba Takes General Assembly Podium To Call For Deep UN Reform. UN News Centre. September 27, 2014 Available Online: http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=48920#.VCy71FYyAds

United Nations (2014b). Members of the United Nations Security Council: Current Members. Available Online: http://internationalrelations.org/wp-admin/post.php?post=1454&action=edit&message=1

Voeten, E. (2007). Why No UN Security Council Reform? Lessons for and from Institutionalist Theory, in Dimitris Bourantonis, Kostas Infantis and Panayotis Tsakonas (eds). 2007. Multilateralism and Security Institutions in the Era of Globalization, Routledge, pages 288-305. Available Online: http://faculty.georgetown.edu/ev42/index_files/Multilateralism_and_Institutions_chapter.pdf

Weiss, T.G. (2003). The Illusion of the UN Security Council Reform. The Washington Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 4, pages 147-161.

Yale Study for the Center of Globalization (2005). Reforming the United Nations for Peace and Security. March 2005, pages 1-196. Available Online: http://www.ycsg.yale.edu/core/forms/Reforming_un.pdf