European Union

The European Union is an International Organization comprised of 28 states throughout Europe. The idea behind the EU is that these different states will come together on a number of issues so that they can reap the benefits of cooperation. Thus, in exchange for some sovereignty, the hope is that these states will benefit economically and politically from being a part of the European Union (European Union, 2014b).

In this article, we examine the European Union. We shall discuss the origins of the European Union, the formation of the international organization, mandate and functions of the IO, as well as debates and criticisms with regards to the organization. We shall also list various references with regards to the European Union.

History of the European Union

The European Union as we know it today first came to existence as the European Economic Community (EEC). The idea behind the European Economic Community was for European states to work together on economic matters following the effects of World War II. The hope was that by increasing trade ties with one another, they would increase trade interdependence, which in turn would help move them away from conflict with one another. It is believed that “French statesmen Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman are regarded as the architects of the principle that the best way to start the European bonding process was by developing economic ties” (BBC, 2012). These ideas led to the Treaty of Paris in 1951 (BBC, 2012), where countries worked together on issues of coal and steel (European Union, 2014b). Shortly after, the European Economic Community was formed in 1958, and was initially comprised of six states, which were Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Luxembourg, as well as the Netherlands (European Union, 2014b). The goal was to “share sovereignty” on a number of matters and issues, which would in turn make conflict increasingly unlikely. For example, the early agreements within the European Economic Community (EEC) focused on economic matters, and specific resources such as coal, steel production, as well as nuclear energy between the states (Archick, 2014).

However, throughout the decades, the European Union has expanded their influence and interdependence greatly. What began as a limited cooperative evolved to include additional issues such as “a customs union; a single market in which goods, people, and capital move freely; a common trade policy; a common agricultural policy; many aspects of social and environmental policy; and a common currency (the euro) that is used by 18 member states” (Archick, 2014: 1). It was in 1991 the that the European Union officially followed the European Community (BBC, 2012). Following the official formation of the European Union, the states within the IO began discussing issues related to citizenship. For example, from this point onwards, individuals from any member of the European Union could travel to any other EU state without restriction (BBC, 2012). And it was in this 1991 European Union Treaty at Maastricht that set European Union positions on issues of rights for workers, amongst other related topics (it should be noted that the United Kingdom did not agree to this ‘Social Chapter’ within the Maastricht Treaty) (BBC, 2012).

How Does the European Union Work?

In terms of currency, the majority of the 28 states are on the same currency, the Euro. Many did so in 1999. Greece, while a part of the Euro, did so in 2001. However, there are a few countries who are not on the Euro. Sweden, Denmark, and the United Kingdom retained their currencies (BBC, 2012). The European Union makes decisions on a host of issues such as economic (trade, agriculture), as well as education, and environmental issues (Archick, 2014). With these decisions, following being agreed upon (through a voting system based on majority vote), they are binding on states (Archick, 2014). There are also discussions on foreign policy, as well as security policy. These issues do not fall within the same category as the previous issues, as they do need the support of all 28 states for the actions to go through.

In 2009, The European Union continues its reform process, and in this action, passed the Lisbon Treaty. The Lisbon Treaty set up the position of the President of the EU, as well as a High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, who is seen as “the EU’s chief diplomat” (Archick, 2014: 3).

The European Union Governance Structure is based on a number of different entities. They are as follows:

European Council: Here, the leaders from all European Union countries, along with the European Commission President meet at “EU Summits” throughout the year. The President is chosen by the European Union states (Archick, 2014). Here, “[t]he European Council defines the general political direction and priorities of the EU but it does not exercise legislative functions” (European Union, 2014b).

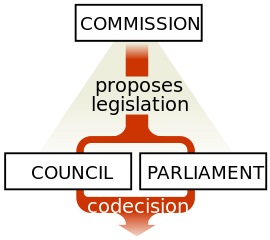

European Commission: The European Commission is seen as the executive of the European Union, is in place to carry out EU decisions, and that treaties are being followed. They are the ones that suggest new laws (European Union, 2014b). With regards to the European Commission, “[i]t is composed of 28 Commissioners, one from each country, who are appointed by agreement among the member states to five-year terms and approved by the European Parliament. One Commissioner serves as Commission President; the others hold distinct portfolios (e.g., agriculture, energy, trade). On many issues, the Commission handles negotiations with outside countries. The Commission is also the EU’s primary administrative entity” (Archick, 2014: 2).

The Council of the European Union/Council of Ministers: The Council of Ministers pushes forward with proposals that come from the European Commission (which are supported by the European Parliament). Here, each country has ministers based upon the issue being discussed. The decisions here are on a “complex majority voting system, but some areas–such as foreign and defense policy, taxation, or accepting new members–require unanimity” (Archick, 2014: 2).

European Parliament: There are a total of 751 elected officials within the European Parliament. They come from all of the EU states, and are serving five year terms. The seats are distributed based on the populations of the European Union countries. The European Parliament itself cannot introduce legislation, although “it shares legislative power wit the Council of Ministers in many policy areas, giving it the right to accept, amend, or reject the majority of proposed EU legislation in a process known as the “ordinary legislative procedure” or “co-decision.” The Parliament also decides on the allocation of the EU’s budget jointly with the Council. Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) caucus according to political affiliation, rather than nationality… (Archick, 2014: 2).

European Court of Justice: The European Court of Justice is the legal institution of the European Union. The ECJ is primarily focused on all legal aspects with regards to the EU; it serves to interpret laws through the EU, and its decisions are binding (Archick, 2014: 2).

European Central Bank: The European Court of Justice is primarily focused on issues related to European Union monetary policy. Its primary attention is on issues related to the Euro (Archick, 2014: 2).

European Union Currency: The Euro

Of the 28 states within the European Union, 18 of them are in the Economic and Monetary Union. These states have decided to tie their economics together further, and are all on the Euro. These countries are: “Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. Lithuania is expected to adopt the euro in January 2015” (Archick, 2014: 4). But despite the fact that these various states all use the Euro, “they do not have a common fiscal policy and member states retain control over decisions about national spending and taxation, subject to certain conditions designed to maintain budgetary discipline. The 18 EMU participants are often collectively referred to as “the Eurozone” (Archick, 2014: 4).

The “Eurozone” crisis was the recent financial issues facing a number of Eurozone countries. For example, one of the first states within this crisis was Greece, who was borrowing money internationally in order to pay its national budget, as well as any trade deficits that they country had accrued. However, this concerned financial investors, who, in 2009, seeing the increase in government debt, were calling for increased interest rates on Greece’s bonds. This in turn let to higher costs, and in 2010, Greece was close to defaulting on the debt that it owed. From this, other European Union countries such as Italy, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain were also concerned about their debt ratios.

And because of these concerns, the European Union, as well as the International Monetary Fund, bailed out Greece, Ireland, Cyprus, as well as Portugal with loans. However, it was not without conditions, with were primarily seen as a range of austerity measures (Archick, 2014). And while it seems that the situation in many of these states has improved, there are still concerns with regards to low growth and high unemployment (Archick, 2014: 5). And because of this recent history with regards to state financial issues, the European Union has attempted to reign in government monetary actions. They have tried to do so with the passing of a “fiscal compact” in which states are expected to follow. The fiscal compact focuses on balanced budgets, as well as an easier ability to levy sanctions against a country that does not follow the rules set out by the European Union. This new fiscal compact went into effect beginning in 2013 (Archick, 2014).

Joining the European Union

The initial criteria for jointing the European Union were laid out in the 1991 Maastricht Treaty. According to Article 49 of the Treaty on the European Union, states are able to apply to the EU if they are believed to have met all standards and criteria set forth within the European Union. However, this alone is not enough, since the European Union itself has the choice of saying when they are ready to add additional members (Morelli, 2013: 1). However, even if the European Union agrees on the possibility of accepting new states as members, this is only the beginning of an arduous process. As Morelli (2013) explains, “The EU operates comprehensive approval procedures that ensure new members are admitted only when they have met all requirements, and only with the active consent of the EU institutions and the governments of the EU member states and of the applicant country. Basically, a country that wishes to join the EU submits an application for membership to the European Council, which then asks the EU Commission to assess the applicant’s ability to meet the conditions of membership” (1). He goes on to discuss the more detailed process, which is quoted below:

Accession talks begin with a screening process to determine to what extent an applicant meets the EU’s approximately 80,000 pages of rules and regulations known as the acquis communautaire. The acquis is divided into 35 chapters that range from free movement of goods to agriculture to competition. Detailed negotiations at the ministerial level take place to establish the terms under which applicants will meet and implement the rules in each chapter. The European Commission proposes common negotiating positions for the EU on each chapter, which must be approved unanimously by the Council of Ministers. In all areas of the acquis, the candidate country must bring its institutions, management capacity, and administrative and judicial systems up to EU standards, both at national and regional levels. During negotiations, applicants may request transition periods for complying with certain EU rules. All candidates receive financial assistance from the EU, mainly to aid in the accession process. Chapters of the acquis can only be opened and closed with the approval of all member states, and chapters provisionally closed may be reopened. Periodically, the Commission issues “progress” reports to the Council (usually in October or November of each year) as well as to the European Parliament assessing the progress achieved by a candidate country. Once the Commission concludes negotiations on all 35 chapters with an applicant, a procedure that can take years, the agreements reached are incorporated into a draft accession treaty, which is submitted to the Council for approval and to the European Parliament for assent. After approval by the Council and Parliament, the accession treaty must be ratified by each EU member state and the candidate country. This process of ratification of the final accession treaty can take up to two years or longer” (Archick & Morelli, 2006, in Morelli, 2013: 1).

European Union Countries

There are currently 28 countries within the European Union. We have listed the European Union countries and the year they entered (European Union, 2014a) into the European Union below.

Austria (1995); Belgium (1952); Bulgaria (2007); Croatia (2013); Cyprus (2004); Czech Republic (2004); Denmark (1973)

Estonia (2004); Finland (1995); France (1952); Germany (1952); Greece (1981); Hungary (2004); Ireland (1973)

Italy (1952); Latvia (2004); Lithuania (2004); Luxembourg (1952); Malta (2004); Netherlands (1952); Poland (2004)

Portugal (1986); Romania (2007); Slovakia (2004); Slovenia (2004); Spain (1986); Sweden (1995); United Kingdom (1973)

Along with the current members of the European Union, there are also discussions about potentially expanding the number of European Union countries. For example, there are a number of “candidate countries” which are trying to work towards entrance into the European Union. The candidate countries are Albania, Iceland, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Turkey. There are also two “potential candidates,” which are Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo (European Union, 2014a).

There are also countries that chose not to be a part of the European Union. For example, Norwegians voted on the issue of the European Union twice, but in both cases, the measure failed (although the votes were close). The concern by countries such as Norway has been issues of economic control over their oil, as well as fishing (Euronews, 2013). However, many of these countries such as Norway, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein still have strong ties to the EU.

The European Union and Security Issues

The European Union has attempted to work towards a unified domestic and international security policy.

Successes of the European Union

The European Union (2014b) has argued that there have been many successes that have come out of the European Union international organization. For example, it has argued that through the EU, the countries and the half a billion citizens of these states can trade goods and services freely. In addition, there is also the establishment of the Euro, which the EU has argued is not only a key currency in the world, but also that it helps in terms of financial efficiency. Moreover, the European Union “is also the largest supplier of development and humanitarian aid programs in the world” (European Union, 2014b). They also point out that they have been quite active on issues such as fighting climate change (European Union, 2014), and continue to work together on various international issues that include but are not limited to security concerns.

Criticisms of the European Union

There have been a number of criticisms regarding the decisions and policies of the European Union in recent years. We have listed a few below.

Expanded Membership of the EU:

A continued criticism of the European Union has been its decisions to not only enlarge the overall membership of the international organization, but also its plans to possible further expand the number of countries within the European Union. As mentioned, the European Union saw a number of new European countries become members in the European Union. Supporters of this felt that adding more countries would bring Europe closer together, and in turn make it a stronger international actor. However, there were many that have been quite critical of this increase, particularly since the “average GDP per head for the new member states was 40% of the average for existing EU countries, making them an economic burden” on the current European Union (BBC, 2012).

Turkey and the European Union:

While some have criticized allowing too many European states into the European Union, others have criticized the process of discussions with regards to Turkey and the European Union. The European Union began talks with Turkey in 2005 with regards to membership. However, in recent years, the two sides have move very little towards an agreement. In 2012, the European Union states have tried to advance a “positive agenda” with regards to Turkey. Furthermore, the European Union has also examined the status of Turkey’s advancement towards membership. For example, as Morelli (2013) explains, “In October 2012, the European Commission issued its annual assessment of the progress of the candidate countries, including Turkey. This was followed in December 2012 by the European Council’s “conclusions” on enlargement, and in April 2013 with the European Parliament’s Progress Report on Turkey. All three reports, while restating Turkey’s importance to the EU and offering a few positive conclusions, expressed overall disappointment with Turkey’s progress on number of issues including judicial reform, media freedom, freedom of expression, Turkey’s continued refusal to extend diplomatic recognition to EU member Cyprus, and Turkey’s position on the Cyprus EU presidency. All three institutions urged Turkey to achieve more reforms” (Morelli, 2013). And while some states pushed for reopening talks in 2013, these were delayed due to summer protests in Turkey, and the criticism of the authoritarian-styled government response (Morelli, 2013).

Scholars have examined the various arguments with regards to Turkey’s ascension into the European Union. It has been argued by some that one of the primary reasons as to why Turkey has not been accepted into the EU has to do with its position as a Muslim majority country, something that some states have not been as willing to accept with regards to membership in the EU. Others have suggested that Turkey’s size is one that would not be conducive to the EU, as they see Turkey as too big of a country (Morelli, 2013). Others have argued that the primary issue for not accepting Turkey into the European Union has to do less with their religious makeup, and more to do with Turkey’s policies towards Cyprus. For example, Morelli (2013) explains that Turkey signed a European Union Protocol in 2005, but within it specifically stated that “it was not granting diplomatic recognition to the Republic of Cyprus. Turkey insisted that recognition would only come when both Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities on the island were reunited. Ankara further stated that Turkey would not open its seaports or airspace to Greek Cypriot vessels until the EU ended the “isolation” of the Turkish Cypriots by providing promised financial aid that at the time was being blocked by Cyprus and opened direct trade between the EU and the north” (3).

European Union Financial Crises:

One of the biggest criticisms of the European Union has to do with expected actions compared to actual actions carried out by its member states. Fiscally, European Union countries are expected to follow specific regulations with regards to debt. However, when looking at the various financial crises in Europe, a number of European states who were in fiscal trouble were so partly because of higher debt ratios than what has been called for in the European Union. For example, in 2009, Greece had a debt of 113% of GDP, which was almost double the called limit in the European Union (the limit was 60 percent) (BBC, 2012). However, Greece was far from the only European Union country in financial trouble. For example, “[i]n November 2010, an EU/IMF bail-out package totalling 85bn euros was agreed on for Ireland, and in May 2011 a 78bn-euro bail-out was approved for Portugal. By the end of the summer the indebtedness of Spain, Italy and Cyprus was also becoming a cause for concern” (BBC, 2012). Furthermore, “[s]igns that the debt contagion was spreading beyond the periphery of the eurozone gave rise to a clamour of calls for urgent action, and at an emergency summit in October 2011, Europe’s leaders agreed on a package of measures that included boosting the eurozone’s main bailout fund to 1tn euros” (BBC, 2012).

In fact, these actions have started to cause some tension within the European Union countries. For example, France and Germany, whose economics have been some of the stronger ones within the European Union, have been upset that they have had to bear a significant burden in bailing out other European Union countries. And citizens in these countries have also expressed similar frustrations to their leaders. And Britain, also wanted “safeguards for its own financial sector” (BBC, 2012). For example, one can see these concerns manifested in recent discussions regarding the European Union and the bailouts.

Greece:

For example, Greece is in talks with the European Union and the International Monetary Fund over the last conditions with regards to their bailouts. On November 18th, 2014, it was reported that “Prime Minister Antonis Samaras’s government is resisting pressure from the so-called troika of creditors for additional budget savings in 2015 of as much as 2.5 billion euros ($3.1 billion), said the people, who asked not to be named because the negotiations are private. The impasse risks leaving Greece without a backstop on Jan. 1 after the program ends, they said” (Chrysoloras, 2014). However, lenders are upset because they feel Greece has not done nearly enough to fulfill its obligations based on the conditions set forth with the loans (Chrysoloras, 2014). And for Greece to enter into a new program with the IMF and the European Union, they will need to be seen to fulfill the current obligations. However, because of these issues, on November 18th, “Uncertainty over what happens once the euro area rescue package expires has triggered a spike in Greek borrowing costs, with yields on 10-year bonds rising from their post-crisis low of 5.5 percent in September” (Chrysoloras, 2014). And yet, many in Greece have be upset at the continued austerity measures in place (Reuters, 2014).

And while there have been attempts to reign control of local government finances (such as a European treasury that dictates state budgets, but there have still been questions about how this would resolve questions of debt within the European Union (BBC, 2012). For example, the vast majority of European Union states are expected to have national deficits for the upcoming year (Chrysoloras, 2014).

Leaving the European Union

Because of concerns with regards to the financial crisis, as well as other policies in the European Union, there have been rumblings by some actors within European Union states that they would consider the possibility of leaving the European Union. In another articles, we discuss the Brexit vote and the UK planning on leaving the European Union.

Concerns About the Future of the European Union

Following the UK’s vote to leave the European Union, other member state leaders have been discussing the future of the international organization. For example, it was reported on September 16, 2016 that EU leaders met in Bratislava, Slovakia do discuss the European Union. German Chancellor Angela Merkel was quoted as saying that the European Union is in a “critical situation” and that they need to show they can work on issues such as security, and fighting terrorism more effectively. While they would not directly address the UK’s exit (since they were not present at the meeting), French leader Francois Hollande said that “”Either we move in the direction of disintegration, of dilution, or we work together to inject new momentum, we relaunch the European project.””

References

Archick, K. (2014). The European Union: Questions and Answers. Congressional Research Service. September 29, 2014. Available Online: http://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RS21372.pdf

Archick, K. & Morelli, V.L. (2006). European Union Enlargement. CRS Report for Congress. RS 21344. October 25, 2006. Available Online: http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/76881.pdf

BBC (2012). Profile: The European Union. 27 June 2012. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/country_profiles/3498746.stm

BBC (2016). Bratislava EU meeting: Merkel says bloc in ‘critical situation.’ BBC. September 16, 2016. Available Online: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-37380429

Chrysoloras, N. (2014). Greek Bailout Review Stalls as Troika Demands Final Steps. Bloomberg November 18th, 2014. Available Online: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-11-17/greek-bailout-review-stalls-as-troika-demands-final-steps.html

Euronews (2013). Why Isn’t Norway in the EU? U Talk. 29/03/13. Available Online: http://www.euronews.com/2013/03/29/norway-and-the-eu/

European Union (2014a). Countries. List of Countries. Available Online: http://europa.eu/about-eu/countries/index_en.htm

European Union (2014b). How the EU Works. Available Online: http://europa.eu/about-eu/index_en.htm

Morelli, V.L. (2013). European Union Enlargement: A Status Report on Turkey’s Accession Negotiations. Congressional Research Service. August 5, 2013. Available Online: http://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RS22517.pdf

Reuters (2014). Thousands of Greeks March Against Austerity To Mark 1973 Uprising. Monday November 17th, 2014. Available Online: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/11/17/us-greece-anniversary-idUSKCN0J122920141117