Oromo Protests

In this article, we shall examine the history of the Oromo protests in Ethiopia. We shall answer the questions “What are the Oromo Protests?”, and discuss in greater context the treatment of the Oromo people in Ethiopia. Within this answer, we shall discuss the history of the Oromo people in Ethiopia, and recent developments in the country. This topic is very important in international relations, as it relates to human rights and a people’s struggle against a repressive regime.

Who are the Oromo People?

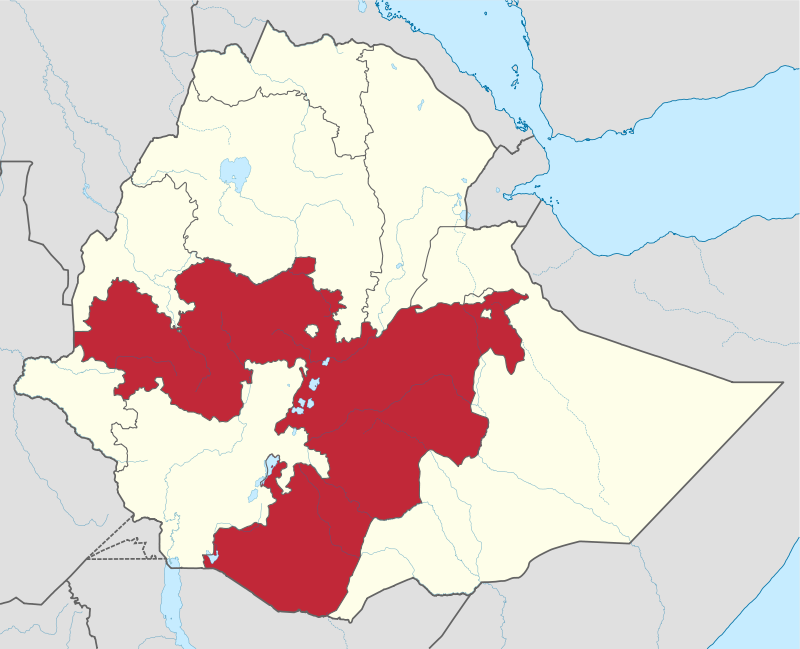

The Oromo People are an indigenous group who have lived in Ethiopia for centuries. Depending on different figures, some believe that the Oromo people have been in Ethiopia since the 1300s, whereas others within the group place the number at the 900s, if not earlier (Iaccino, 2016). Today, the Oromo people make up over 25 million people, which is 35 percent of the entire population in Ethiopia (Iaccino, 2016) (according to the 2007 census, which was out of a population of 75 million (Gaffey, 2016) (current population figures are at 99 million persons) (Kuo, 2016) (the government, made up primarily of Tigray people, makes up 6 percent of the entire population) (Kuo, 2016). There are two major groups within the Oromo people: there are the Borana Oromo, which are mainly in southeastern Ethiopia as well as in the country of Kenya. Along with the Borana Oromo, there is also the group Barentu Oromo, who are in Oromia (a state within Ethiopia; “The state should not be confused with the Oromia Zone, in the Ahmara region, northern Ethiopia. This zone is inhabited by some 450,000 people. This area was created following pressures by Oromo groups that called for self-determination” (Iaccino, 2016)), The Barento Oromo people are also in other parts of Ethiopia and also Somalia (Iaccino, 2016). With regards to the religion of the Oromo people, the vast majority of Oromo are Christian and Muslim; 3 percent of the Oromo people continue to practice an indigenous faith, where the deity is Waaq (Iaccino, 2016).

Looking at the history of the Oromo people in Ethiopia, they have traditionally been farmers. Politically, the land of the Oromo people was challenged by various groups. Ethiopia was not colonized by outside powers , but internal political struggles for power did occur (conflict between the Oromo people and Ethiopians began as early as the 1500s until the end of the 1800s) (Jalata, 2005). Towards the latter part of the 1800s, through an internal monarchy in Ethiopia, “Menelik II began expanding the empire by conquering and forcibly incorporating southern and western areas, including what was known derogatorily as Galla Land, referring to the Oromo, into the Amhara-dominated Ethiopian empire” (The Advocates for Human Rights, 2009). For example, in 1886, the kingdom of Abyssinia moved on Oromia, and established Addis Ababa. It was at this time that many of the Oromo people working in the land were moved out (Iaccino, 2016). The government’s argument for doing this was to ensure that they could protect the country against any internal rebellions. However, this action greatly affected the Oromo people (The Advocates for Human Rights, 2009).

Throughout the late 1800s and 1900s, the human rights abuses against the Oromo people continued in the form of education discrimination, economic discrimination, or state violence (Jalala, 2003). Furthermore, “[t]he Ethiopian colonial state and its institutions prevented the emergence of an Oromo leadership by co-opting many of the intellectual elements, liquidating the nationalist ones, suppressing Oromo autonomous institutions, and erasing Oromo history, culture, and language” (Jalala, 2003: 81). These human rights abuses against the Oromo people continue into and through the 20th century.

For example, “Although Oromos provided resources to build Ethiopian infrastructures and institutions, they were denied access to social amenities. In May 1966, the association reflected on this reality at its Itaya meeting: “(1) less than one percent of Oromo school-age children ever get the opportunity to go to school; (2) …less than one percent of the Oromo population get adequate medical services; (3) …less than fifty percent of the Oromo population own land; (4)… a very small percentage of the Oromo population has access to [modern] communication services. [And yet] the Oromo paid more than eighty percent of the taxes for education, health, and communication” (in Hassen, 1998: 205-206) (Jalata, 2003: 83), but, they were purposely kept from being educated, so that they would continue to submit under the power of the Ethiopian government (Jalata, 2005).

Haile Selassie, who was in power until 1974, continue the rights oppression against the Oromo by pushing for the use of the Amharic language, at the expense of the Oromo language (The Advocates for Human Rights, 2009); Haile Selassie even stopped musical groups from performing due to performances being done in the Oromo language. Furthermore, Selassie also went after Oromo groups and their political leadership (Jalala, 2003).

Throughout the decades, the Ethiopian government embarked on policies of terrorism against the Oromo people, going against farmers, political leaders, and many others whom they see as a threat to their rule, and because of their interests in Oromo land and economic resources (Jalala, 1997, in Jalala, 2003). As Jalata (1995) explains, “Ethiopians have been very resistant to the emergence of Oromo nationalism because Oromos are the numerical majority, and Ethiopia mainly depends on Oromo economic and labour resources. Therefore, rather than deal democratically with the Oromo movement, Ethiopians have tried their best to totally destroy it” (165). Jalata (1995) goes on to say that “Oromo culture, history, and language have been despised and repressed by Ethiopians, who considered them primitive, backward, and inferior” (167).

What are the Oromo Protests?

In order to understand the Oromo protests today, it is imperative to examine the history of discrimination that the Oromo people have faced in Ethiopia. Not only were their lands taken by other powers in the country, but the group has not been granted full rights in accord with what others have received. For decades, governments have ignored the plight of the Oromo people. For example, the government suppressed the Oromo people’s language for decades until more recently (BBC, 2016).

Due to the various human rights abuses agains the Oromo people, “In 1973, Ethiopian Oromo created the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), which stemmed from the discontent among people over a perceived marginalisation by the government and to fight the hegemony of the Amhara people” (Iaccino, 2016). The Oromo Liberation Front is a terror organization, as they have used violence against noncombatants for their political objectives.

In addition, the “Oromo language was sidelined and not taught in schools for much of the 20th century and Oromo activists were often tortured or disappeared. A 2009 report by the United Nations Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) stated that 594 extra-judicial killings and 43 disappearances of Oromos were recorded between 2005 and 2008 by an Oromo activist group” (Gaffey, 2016). The government has not only restricted language, but they have also arrested some within the Oromo Federalist Congress (the legally recognized party) and many other political prisoners from the Oromo people (BBC, 2016).

Regarding the issue of the Oromo language, “The government’s tactics have extended to the educational system, where Oromo teachers and students face harassment and intimidation on suspicion of association with the OLF. Reports of monitoring, termination, or arrest of Oromo teachers and students were common. The mandatory use of the Oromo language in schools, reversing the decades old policy prohibiting instruction in any language other than Amharic, has not apparently lessened government suspicion that people who speak or write in the Oromo language support the OLF. The requirement of instruction in Oromo has also reportedly led to a decrease in educational opportunities for Oromo students, who are now at a disadvantage in the higher education system where Amharic or English is required” (The Advocates for Human Rights, 2009: 2).

In 1991, following the removal of the military regime, the new government called for a new system of governance in Ethiopia, which is structured on an ethnic federalist based system (BBC, 2016) so as to provide more power for the different ethnic groups. The problem however is not in this system, but rather, that the national government continues to be dominated by one group, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) (BBC, 2016). So, the Oromo people are calling for these rights that the government promised, and the state seems not only less than willing to provide these rights, but they have themselves response to the Oromo protests in Ethiopia with violent actions (BBC, 2016).

Furthermore, “When the current government came into power a quarter of a century ago, it pursued a strategy of divide and rule in which the Oromos and Amharas, the two largest ethnic groups in the country, are presented as eternal adversaries. Oromos are blamed as secessionists to justify the continued monitoring, control, and policing of Oromo intellectuals, politicians, artists and activists. By depicting Oromo demands for equal representation and autonomy as extremist and exclusionary, it tried to drive a wedge between them and other ethnic groups, particularly the Amharas. This allowed the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front and Tigrayan elites to present themselves as the only political movement in the country that could provide the stability and continuity sought by regional and global powers with vested interest in the region.” (Allo, 2016).

The latest round of Oromo protests began in April of 2014 following government plans of expanding their territory into the Oromo region. According to activists, as many as 47 people were killed in April and May of 2014 following Oromo protests against the Ethiopian government. As Amnesty International (2014) wrote in their 2014 report “Because I am Oromo,” “The Government of Ethiopia is hostile to dissent, wherever and however it manifests, and also shows hostility to influential individuals or groups not affiliated to the ruling Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) political party. The government has used arbitrary arrest and detention, often without charge, to suppress suggestions of dissent in many parts of the country. But this hostility, and the resulting acts of suppression, have manifested often and at scale in Oromia” (8).

They also noted that “Between 2011 and 2014, at least 5,000 Oromos have been arrested as a result of their actual or suspected peaceful opposition to the government, based on their manifestation of dissenting opinions, exercise of freedom of expression or their imputed political opinion. These included thousands of peaceful protestors and hundreds of political opposition members, but also hundreds of other individuals from all walks of life – students, pharmacists, civil servants, singers, businesspeople and people expressing their Oromo cultural heritage – arrested based on the expression of dissenting opinions or their suspected opposition to the government. Due to restrictions on human rights reporting, independent journalism and information exchange in Ethiopia, as well as a lack of transparency on detention practices, it is possible there are many additional cases that have not been reported or documented” (8).

Following the April and May protests, 140 people were said to be killed in November 2015 protests (Gaffey, 2016). Then, in 2015, the Oromo Liberation Front spoke out against the Ethiopian government, and condemned what they viewed as 25 years of oppression, violence and killing against the Oromo people. In December of 2015, they spoke of restarting “a second round of war”, which is based on the protests in Oromia (Iaccino, 2016). The 2014 and 2015 Oromo protests were based on the governments plan to expand the capital city of Addis Ababa in Ethiopia. The Oromo people are worried that doing this will affect Oromo farmers, who will lose land, and will suffer economic problems because of government actions (Iaccino, 2016). However, because of the backlash, the government scrapped the plan. But this did not stop the Oromo protests. But the expansion plans were just the last action against the Oromo people in Ethiopia, which is why the Oromo protests have continued.

In fact, the Oromo protests continued throughout the 2016 year, and are still ongoing. For example, in February of 2016, according to reports, “A bus filled with a wedding party taking the bride to the groom’s home was stopped at a routine checkpoint on 12 February near the southern Ethiopian town of Shashamane. Local police told revellers to turn off the nationalistic Oromo music playing. They refused and the bus drove off. The situation then rapidly escalated and reports indicate at least one person died and three others were injured after police fired shots” (BBC, 2016). Even though it is tough to know exactly what transpired, the result was more violence between militia forces and police (BBC, 2016).

For example, in October of 2016, the Oromo congregated to celebrate a religious holiday. However, the gathering then turned to a stampede in which 52 people died. According to reports, “Activists say the stampede began after police fired tear gas and rubber bullets into a peacefully chanting crowd. Groups gathered at the festival had begun chanting the anti-government slogan “down, down TPLF,” referring to the ruling Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front, and holding their arms up, crossed at the wrist—a gesture of the current protest movement meant to symbolize being handcuffed” (Kuo, 2016). However, human rights activists say the number was not 52, but in the mid hundreds (with over 500 people being killed) after Ethiopian authorities shot into crowds (something the government disputed) (Busari, 2016).

The government has been criticized not only for not providing the equal rights others in Ethiopia have received, but also for cracking down on the Oromo protesters. The government claimed that the protests were used by others to intensify and instill violence in Ethiopia (BBC, 2016).

Given the rising tensions from the Oromo protests, on October 9th, 2016, the Ethiopian government declared a state of emergency. This state of emergency was called for six months. As a result of the state of emergency Oromo politicians and their supporters have spoken out against the action. For example, Merera Gudina (as well as three others) were arrested after Gudina spoke to the European Parlaiment on November 9th, 2016 criticizing the state of emergency (Schemm, 2016).

Conclusion

The Oromo Protests continue to be an ongoing situation in Ethiopia. The Oromo people have continued to face human rights abuses by a government unwilling to grant them equality on all levels. So, the Oromo protests are about demanding these rights. Despite government accusations that they are led by a terror organization, protesters are using non-violence as a form of civil action. They are primarily not looking to break away from Ethiopia (Gaffey, 2016), but rather, they want human rights.

Oromo Protests References

Allo, A.K. (2016). Oromo protests: Why US must stop enabling Ethiopia. CNN. August 9, 2016. Available Online: http://www.cnn.com/2016/08/09/africa/ethiopia-oromo-protest/

Amnesty International (2014). Because I am Oromo: Sweeping Repression in the Oromia Region of Ethiopia. Amnesty International. 28 October 2014. Available Online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr25/006/2014/en/

BBC (2016). What do Oromo protests mean for Ethiopian unity? BBC News. 9 March 2016. Available Online: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-35749065

Busari, S. (2016). Ethiopia declares state of emergency after months of protests. CNN. October 11, 2016. Available Online: http://www.cnn.com/2016/10/09/africa/ethiopia-oromo-state-emergency/

Gaffey, C. (2016). Oromo Protests: Why Ethiopia’s Largest Ethnic Group is Demonstrating. Newsweek. 2/26/2016. Available Online: http://www.newsweek.com/oromo-protests-why-ethiopias-biggest-ethnic-group-demonstrating-430793

Hassen, M. (1998). “The Macha-Tulama Association 1963-1967 and the Development of Oromo Nationalism.” A. Jalata (ed.), Oromo Nationalism and the Ethiopian Discourse. Lawrenceville, NJ: The Red Sea Press: 183-221.

Iaccino, L. (2016). Addis Ababa master plan: Who are the Oromo people, Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group? International Business Times. January 12, 2016. Available Online: http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/addis-ababa-master-plan-who-are-oromo-people-ethiopias-largest-ethnic-group-1533664

Jalata, A. (1995). The Emergence of Oromo Nationalism and Ethiopian Reaction, Social Justice, Vol. 22, No. 3 (61), Racial & Political Justice (Fall 1995), pages 165-189.

Jalata, A. (1997). Nationalism in the New Global Context.” The Journal of Oromo Studies 4,1-2: 83-114.

Jalata, A. (2003). Comparing the African American And Oromo Movements in the Global Context. Social Justice, Vol. 30, No. 1 (91), pages 67-111.

Kuo, L. (2016). Ethiopia is in a a state of national mourning after 52 Oromo protesters were killed in a stampede. Quartz Africa. October 3, 2016. Available Online: http://qz.com/798798/ethiopia-is-in-a-state-of-national-mourning-after-52-oromo-protesters-were-killed-in-a-stampede/

Schemm, P. (2016). Ethiopia arrests top Oromo opposition politician after Europe Parliament speech. Yahoo News. December 1st, 2016. Available Online: https://www.yahoo.com/news/m/76e0b2d1-82fc-3248-b8e5-44b65c6383af/ethiopia-arrests-top-oromo.html

The Advocates for Human Rights (2009). Human Rights in Ethiopia: Through the Eyes of the Oromo Diaspora. The Advocates for Human Rights. December 2009. Available Online: http://www.theadvocatesforhumanrights.org/uploads/oromo_report_2009_color.pdf