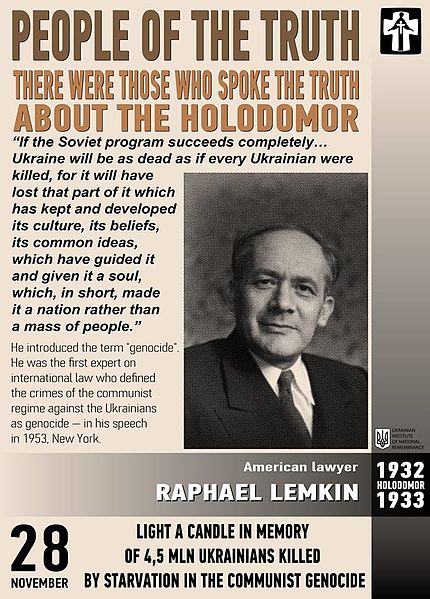

Raphael Lemkin

Raphael Lemkin was a very important human rights activist who shaped the way we speak about human rights violations. Lemkin left a lasting legacy as it pertains to the human rights movement. For example, Jeff Benvenuto (2013) writes of Lemkin: “he was one of the most impressive figures of 20th century history. A modern day “renaissance man,” he was fluent in almost a dozen languages, a jurisprudential marvel, a politically astute lobbyist and campaigner, a keen student of the social sciences, and a devoted admirer of the arts.”

In this article, we shall discuss the legacy of Raphael Lemkin, and his work in human rights and international law. We will briefly discuss his biography, as well as his human rights work.

Who was Raphael Lemkin?

Raphael Lemkin was born on June 24, 1900, in Belorussia. He began his university studies at Lvov Univeristy in 1920, and earned a doctorate in the field of law in 1926. Then, in 1929-1934, Lemkin worked as a prosecutor in Warsaw, Poland. He was also working as a professor at Takhemoni College, in Warsaw. Here he was hired to work and teach on family law. He worked at Takhemoni College from 1929-1939 (Benvenuto, 2013).

Lemkin was interested in human rights from a young age. For example, he was quite troubled after learning about the atrocities that the Turkish government committed against the Armenians during in the time of World War I. He commented on these events, saying, “”I was shocked…” “Why is a man punished when he kills another man? Why is the killing of a million a lesser crime than the killing of a single individual?” (Hyde, 2008).

Sadly, Hitler coming to power in Germany began a horrific campaign against the Jewish people, along with others in Germany and in Europe. When Hitler and the Nazis attacked Poland in the year 1939, Lemkin needed to flee, having to survive in the woods while the conflict was engulfing the country, and the Nazis were continuing to commit massive crimes. From Poland, Lemkin came to the United States, where he was employed at Duke University Law School (Hyde, 2008).

While in the United States, Lemkin was furious at the lack of attention levels towards the crimes and killings that the Nazis were committing in Europe. And because of this, he began advocating to US leaders and others about the need to stop that actions of Hitler and the Nazis. He even wrote to President Roosevelt, urging him to act. However, when the President replied calling for “patience,” Lemkin wrote about this, saying that “”Patience…”, “But I could bitterly see only the faces of the millions awaiting death. … All over Europe the Nazis were writing the book of death with the blood of my brethren” (reported in Hyde, 2008).

Lemkin and The Term Genocide

Raphael Lemkin was the first individual to coin the word “genocide.” Lemkin invented this term in 1944 in his writings on the Nazi killings of Jews, Roma, and others. He wrote about the genocide, saying:

By “genocide” we mean the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group. This new word, coined by the author to denote an old practice in its modern development, is made from the ancient Greek word genos (race, tribe) and the Latin cide (killing), thus corresponding in its formation to such words as tyrannicide, homocide, infanticide, etc.(1) Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups. Genocide is directed against the national group as an entity, and the actions involved are directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group (Lemkin, 1944).

In addition to merely calling particular acts as genocide, he devoted his life to speaking out against acts of genocide, while bringing attention to these acts that were committed by different governments, whether it was Russia or the Ottoman Empire against the Armenians. Following hearing about these killings, he committed himself to fighting against genocide and human rights abuses. Lemkin began writing international law condemning such crimes. As Hyde (2008) writes: “By October 1933, Lemkin was an influential Warsaw lawyer, well-connected and versed in international law. At the same time, Hitler was gathering power. Lemkin knew it was time to act. He crafted his proposal making the destruction of national, racial and religious groups an international crime and sent it to an influential international conference. But his legal remedy found little support, even as anti-Semitism was becoming Germany’s national policy. When Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, Lemkin knew his worst fears were about to be realized.”

However, despite the specific creation of the term in 1944, Lemkin was writing on the issue of genocide, before he coined the term. For example, Lemkin called for a number of punishments for crimes committed towards groups based on various identities. The seven articles from the proposed 1933 text (Lemkin, 1933) are listed below:

PROPOSED TEXT Art. 1) Whoever, out of hatred towards a racial, religious or social collectivity or with the goal of its extermination, undertakes a punishable action against the life, the bodily integrity, liberty, dignity or the economic existence of a person belonging to such a collectivity, is liable, for the offense of barbarity, to a penalty of . . . unless punishment for the action falls under a more severe provision of the given Code.The author will be liable for the same penalty, if an act is directed against a person who has declared solidarity with such a collectivity or has intervened in favor of one.

Art. 2) Whoever, either out of hatred towards a racial, religious or social collectivity or with the goal of its extermination, destroys works of cultural or artistic heritage, is liable, for the offense of vandalism, to a penalty of . . . unless punishment for the action falls under a more severe provision of the given Code.

Art. 3) Whoever knowingly causes a catastrophe in the international communication by ground, sea or air by destroying or removing the systems which ensure the regular operation of these communications, is liable to imprisonment for a period of . . .

Art. 4) Whoever knowingly causes an interruption in the international postal, telegraph or telephone communication by removing or by destroying the systems which ensure the regular operation of these communications, is liable to a penalty of . . .

Art. 5) Whoever knowingly spreads a human, animal or vegetable contagion is liable to a penalty of . . .

Art. 6) The instigator and the accomplice are subject to the same punishment as the author.

Art. 7) Offenses enumerated in Articles 1 – 6 will be prosecuted and punished independently of the place where the act was committed and of the nationality of the author, in accordance with the law in force in the country of the prosecution.

Lemkin began collecting evidence of the plans and atrocities committed by the Nazis. He began writing a detailed book on these events, and it was here that he created the term “genocide” for what what transpiring. However, unfortunately top political actors did little to act quickly to stop the genocide. But Lemkin continued to speak out against the Nazis, and then following the end of World War II, continued to work tirelessly to ensure that international human rights law would be established, and that genocide would be addressed, and made illegal in international law. For example, he spoke about the Genocide that the Nazis were committing, saying in his writings (Lemkin, 1944):

Genocide is the antithesis of the Rousseau-Portalis Doctrine, which may be regarded as implicit in the Hague Regulations. This doctrine holds that war is directed against sovereigns and armies, not against subjects and civilians. In its modern application in civilized society, the doctrine means that war is conducted against states and armed forces and not against populations. It required a long period of evolution in civilized society to mark the way from wars of extermination, (3) which occurred in ancient times and in the Middle Ages, to the conception of wars as being essentially limited to activities against armies and states. In the present war, however, genocide is widely practiced by the German occupant. Germany could not accept the Rousseau-Portalis Doctrine: first, because Germany is waging a total war; and secondly, because, according to the doctrine of National Socialism, the nation, not the state, is the predominant factor. (4) In this German conception the nation provides the biological element for the state. Consequently, in enforcing the New Order, the Germans prepared, waged, and continued a war [p.81] not merely against states and their armies (5) but against peoples. For the German occupying authorities war thus appears to offer the most appropriate occasion for carrying out their policy of genocide. Their reasoning seems to be the following:

And in 1948, his efforts on preventing and speaking out against genocide were instrumental in the writing and passing of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. This document specifically recognized genocide as a specific human rights crime, whether committed during war or outside of war.

Following this convention, Raphael Lemkin continued to work on genocide, speaking with government leaders from around the world to ensure that enough states would ratify the document, thereby putting it into force. The convention was put into force in 1951 (although the United States did not ratify the document until decades later (in 1988)) (UNHCR, 2015).

Lemkin was nominated for the Nobel Peace prize multiple times during his life.

Ralph Lemkin passed away on August 28, 1959 (Benvenuto, 2013).

Works by Raphael Lemkin

Raphael Lemkin wrote a number of articles and books on the issue of human rights and genocide.

Here is a list of writings by Raphael Lemkin cited from Prevent Genocide: We have cited the list below:

Books and Pamphlets

Kodeks Karny Republik Sowieckich Rafal Lemkin & Tadeusz Kochanowicz. (Warszawa: Wyd. Sem. Prawa kar., 1926); Str. 132 + 4 nlb; Wyd. Sem. Prawa kar. Uniw. J.K. we Lwowie. Tlumacyzli z orinalu; przy wspoludziale. Dra Ludwika Dworzada, Mgra Zdzislawa Papierkowskiego, dra Romana Piotrowskiego. Slowo wstepne napisal; prof dr. Juljusz Makarewicz.

[Polish] Criminal Code of the Soviet Republics (Written with Tadeusz Kochanowski).Warsaw: Edition of the pamphlet of Penal Law. Published by the seminarium of Criminal Law of University of Jan Kasimir in Lwow). 132pp. This treatise embraces the historical evolution of Russian and Soviet Penal Law with special attention to its most essential legal principles. Includes a translation into Polish of all 227 articles of the Russian Penal Code of 1922 from the original in collaboration with Dr. Ludwik Dworzad, Magister Zdzilaw Papierkowski and Dr. Roman Piotrowski; Preface by Dr. Julian Makarewicz.

Kodeks Karny Rosji Sowieckiej 1927 Przelozyl i watepem zaopatrzyl; Prezedmowe Napisal Prof. W. Makowski Wydawnictwo seminarjum prawa karnego Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego Warszawa: Sklad Glowny w Ksiegarni F. Hoesicka, 1928; 48pp.

[Polish] Criminal Code of Soviet Russia 1927: translation of all 175 articles and analysis); foreword and introduction provided by Prof. Waclaw Makowski; Published by the Seminarium of Criminal Law of the University of Warsaw; Warsaw Main Depository of the Library of F. Hoesick, 1928); 48pp. On the newly revised Soviet Criminal Code (‘methods of social protection’) ‘of 1927, which replaced the code of 1922. Waclaw Makowski was speaker of the Polish Parliament. Lemkin notes the apparent influence of the admired late 19th-century Italian Positivist School on the code. Lemkin notes, however, that while the reforms claimed to be based on the principle of “social protection”, the substance of the code represented no reform at all.

Orgaanisrung Yiddisch Folk, Organizations of the Jewish People, 80pp. Alternate Polish title page “Organizacja Gmin Zydowsjich” Warszawa 1928

[Yiddish] Volume No. 2 of the the Jewish Law Library published by E. Gitlina, Warsaw. Decrees of the President of the Republic on arranged legal records by organizations of people of Jewish (Mosaic) faith and Electoral regulations for People of Jewish Faith – Decrees on Galicia and in the [Eastern] borderlands.

Kodeks Karny Faszystowski, Italy, Warszawa: Nakladem Ksiegarni F. Hoesicka, 1929; 138pp.

[Polish]. Fascist Criminal Code, Italy, legal and sociological analysis. Preface by Waclawa Makowski; Published by the Library of F. Hoesick, 1929); 138pp. Historical survey of the Penal Code of the 626 article Italy and analysis of the various Penal institutions with special consideration of the penal doctrine and discussions in the Italian Parliament. The book includes the author’s criticism as well as a translation into Polish of the essential parts of the bill.

[Industrial Statutes], Alternate Polish title page “Ustawa Przemyslowa” 193pp.

[Yiddish] Volume No. 3 in the Jewish Law Library published by E. Gitlina, Warsaw. Statutes [ ] and journeyman faculties – Decrees on Commentary and pattern.

Ustawa Karna Skarbowa z dnia z siepina 1926 r. With Jan Karyory Z Dodatkowemi Ustawami, Rozporzadzeniami I Okolnikami Ministertwa Sprawiedliwosci I Skarbu Oraz Orzecznictwem Sadu Najwyzszego I Objasnieniami. Warszawa: Nakladem Ksiegarni F. Hoesicka, 1931; 493pp.

[Polish] The Fiscal Penal Statue of 1926 (written with Jan Koryory, vice president of the Warsaw District Court, with additional edicts, circulars of the Ministries of Justice and Treasury, as well as Verdicts and Explanations of the Supreme Court; Published by the Library of F. Hoesicka); 493pp. A detailed commentary of the Statute.

Opinje O Projekcie Kodeksu Karnego (with Wlodz Sokalski) Warszawa: Wydawnictwo “Bibljoteka icza,” 1931: 65pp.

[Polish]. Commentary on the Polish Penal Law Project of 1932 (with Wlodz Sokalski) Warsaw: Published by the “Law Library,” 1931); 65pp.

Kodeks Karny: Komentarz (Commentary of the Polish Penal Law of 1932). Published in cooperation with Emile-Stanislas Rappaport (and J. Jamontt, professors of law at Warsaw University and Justices of the Supreme Court of Poland. Two volumes. Warsaw, 1932.

[Polish] (Bill of Minor Offenses). (with Professor Emile-Stanislas. Rappaport (Judge of the Supreme Court of Poland) , became law in July 1932.

Amnestja 1932 r. Komentarz Warsaw: Gebethner and Wolff, 1932.

[Polish]. Scientific Treatise and Commentaries on the Statue of 11 November 1932.

Sedzia w obliczu nowoczesnego prawa Karnego i Kryminologji, Wydawnictwo Instytutu Kryminologicznego Wolnej Wszechnicy Polskiej. Warsawa 1933.

[Polish]. (The Judge in the Face of Modern Penal Law Problems and Criminology, Habilitation Work; Warsaw: Warsaw University Institute for Criminology, 1933. Section A: The Judge’s Competencies Examined from the Standpoint of Legislation and Philosophy, Section B: Criminological Basis for the Judgment, Section C: Penal Judge’s Specialization. (The psychology and legal limits of the discretionary power of the judge.) Warsaw: Warsaw University Institute for Criminology, 1933. Note: Lemkin includes this item, a major work, in later lists of his publication, but is not known to still exist in any library. A review Izydor Reizler appeared in Glos Prawa, Vol. XI, Nr. 4-5, p. 339-340.

Amnestja 1936 r. Komentarz Ustawa z dn. Z stycznia 1936 r. o amnestji (Dz U. R. P. Nr. 1/36 poz. 1). Komentarze. Motywy ustawodawcze. Orzecznictwo Sadu Najwyzszego. Okolniki ministerjalne. Warszawa: Ksiegarna Powszechna, 1936, 80pp.

[Polish] Commentary of the Amnesty Decree of 1936) Commentary, Legislative Motivations, Opinions of the Supreme Court, Circulars of the Ministry; Warsaw: General Library, 80pp.

Stawa Karna Skarbowa z dnia z siepina 1937 r.

[Polish] (The Fiscal Penal Statue of 1937).Third Commentary by Lemkin on Penal Fiscal Statutes, which were reconsidered twice

Encyklopedji Podrecznej Prawa Karnego – Wyd Inst. Wyd, “Bibljoteka Polska” w Warzawiej; Warszawa, 1931-1939; Drukiem Zakladow Grafioznych “Biblioteka Polska” w Bydgoszczy.

[Polish] Encyclopedia of Criminal Law. 27 volumes published between 1931 to 1939.edited by Waclaw Makowski. Lemkin contributed articles on Criminal Law in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, England, Guatemala, Mexico Peru, the Soviet Union and the United States; Among the longer entries are “Criminal Law of Soviet Russia: Criminal Code, Criminal Procedure” (Vol. 25, 1938, 7 pp.) , United States of America “Penal jurisdiction in the United States of North America (Vol. 27, 1939, 10pp)

Encyclopedia of Finance, Article on “tax evasions”[Polish] Warsaw, 1936

The Polish Penal Code of 1932 and The Law of Minor Offenses Translated with Malcolm McDermott. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1939; 95pp.

[English] Translation with Malcolm McDermott (Duke University Law School) of the 295 article penal code, and the 65 article ‘Law of Minor Offenses’. The Introduction “History of Codification of Penal Law in Poland,” by Raphael Lemkin.pages 7-19, mentions Lemkin’s work a member and secretary of the ten-member committee of the Codification Commission. Lemkin and one other member E.S. Rappaport had drafted the text of the ‘Law of Minor Offenses’ . The introduction describes the significance of the principle of ‘universal repression’ provided for the international offenses in Article 9 (Piracy, Counterfeiting, trade in slaves and women and children, narcotics, pornography and terrorism) .

La Regulation des Paiements Internationaux: Traite de droit compare sur les devises, Les clearing et les accords de paiments, Les conflicts de lois, Paris: A. Pedone, 1939; 422pp.

[French]. The Regulation of International Payments. Legal analysis of international business transactions addressing comparative law of foreign exchange, clearing, barter transactions, payment agreements, and conflict of laws in international payments. Preface by Marcel Van Zeeland, director of the Banque de Reglements Internationaux (B.R.I) in Basel, Switzerland. The book describes the freedom of international payments from 1923 to 1927, and details the international movement of governments toward currency exchange control which occurred in late 1931, early 1932 and later, following the collapse of the Credit Anstalt Bank in Vienna in 1931. Instead of devaluing their currencies governments, created such restrictions to keep money from going out of the country. Poland was one of the last governments to adopt such controls, by decree of the President in April 1936. Published late in 1939 after the German and Soviet invasions of Poland and the onset of World War II. Lemkin reviewed the book in page proofs while he was a refugee in Lithuania and sent them to Paris for publication.

Valutareglering och Clearing: Bearbetat efter forfattarens forelasningar vid Stockholms Hogskola hosten 1940. Stockholm: Kungl. Boktryckeriet. P.A. Norstedt and Soner, 1941; 170pp.

[Swedish]. Based on lectures delivered at Stockholm University in 1940 and 1941 on the impact of clearing and exchange controls on conflict of laws the subject of Lemkin’s earlier book, La Regulation des Paiements Internationaux.

Key laws, decrees and regulations issued by the Axis in occupied Europe. Washington: Board of Economic Warfare, Blockade and Supply Branch, Reoccupation Division, December 1942. 170pp.

Lemkin’s English translation of official German decrees.

Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation – Analysis of Government – Proposals for Redress, Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1944, 670pp.

Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, published in November 1944, was the first place where the word “genocide” appeared in print. Raphael Lemkin coined the new word “genocide” in 1943 as part of his analysis of German occupation policies in Europe. French translation: Le règne de l’Axe en Europe occupée, Le premier paragraphe de Chapitre IX: ” Génocide ” de Raphaël Lemkin, 1944. Spanish translation: Las Reglas del Eje sobre la Europa Ocupada, Primer párrafo de Capítulo IX: ” Genocide ” de Raphael Lemkin, 1944. Translation by Carlos Mario Molina Arrubla, May 2000

Articles and Reports presented at Conferences

“Emploi international des moyens capables de faire courir un danger cummun.” rapport à la 4e Conférence internationale pour l’unification du droir penal), no. 8, 1931, Paris: Librarie du Recueil Sirey, 1931; 11 pp.

[French] “The international use of means capable of thwarting a common danger”. Report on Terrorism presented to the Fourth International Conference for the Unification of Penal Law. [add date of the conference]

“La reforme du droit penal en Chine”, Revue de Droit Penal et de Criminologie, no. 8, July 1932. Reprinted Paris: Librarie des Juris-Classeurs, 1932, 9pp.

[French]. The Reform of Chinese Penal Law. Comparisons between ancient Chinese common law and modern Chinese law

“Reue Penitentiare et de Droit Penal et Etudes Criminologiques”, Revue Penitentiare et de Droit Penal et Etudes Criminologiques (Nos. 4-9, 1932).

[French] The Reform of Penal Law in Czechoslovakia

“Le nouveau Code pénal polonais” Revue de Droit et de Criminologie, Vol 12, no. 12 (December 1932), p. 1184

[French] translation with Lemkin’s comments p. 1184-1190

Roy X styczen-Luty 1933 No. 3.

“Ewolucja wtadzy sedziego Karnejo: Reforma prawa karnejo ndtle stosunko jednosthi du zbiorowoky” Palestra: Organ Rady Adwokachiej W. Warszawie..Nr. 3 (March 1933), p. 158-180.

[Polish]the article cites German jurist Kohlrauch on page 175.

“Des quelles manieres pourrait-on obtenir une meilleure specialisation du juge penal?”

[French]. “How can we obtain better specialization of the Penal Judge?” Report presented at the Third Congress of the International Association for Penal Law, held in Palermo in April 1933.

“Les actes constituant un danger general (interétatique) consideres comme delites des droit des gens” Expilications additionelles au Rapport spécial présentè à la V-me Conférence pour l’Unification du Droit Penal à Madrid (14-2O.X.1933).

This report Special report presented to the Fifth Conference for the Unification of Penal Law, held in Madrid, October, 14-20, 1933.was published by Paris law publisher A. Pedone (13, Rue Soufflot) as part of the Librarie de la cour d’appel ed de l’order de advocates. The conference, hosted by Spain was held in collaboration with the Fifth Committee of the League of Nations. English translation: “Acts Constituting a General (Transnational) Danger considered as Crimes under International Law” Translation by James T. Fussell. Another version of this report appeared the official conference proceedings, published in 1935.

“Akte der Barbarei und des Vandalismus als delicta juris gentium“ (Acts of Barbarism and Vandalism under the Law of Nations),Anwaltsblatt Internationales, Vienna,Vol. 19, No. 6, (Nov. 1933), p. 117-119

[German] An abbreviated version of the report ‘General (Transnational) Danger‘ he originally presented in French at the 5th Conference for the Unification of Penal Law in Madrid, Spain in October 1933. The article was published in Anwaltsblatt Internationales (Lawyer Gazette International), a legal monthly based in Vienna, Austria and edited by Dr. Rudolf Braun.

“Przestepstwa, polegajace na wywolaniu niebezpieczenstwa miedzypanstwowego jako delicta iuris gentium” (wnioski na V Miedzynarodowa Konferencje Unifikacji Prawa Karnego w Madrycie), Glos Prawa, Nr, 10, Lwów, pazdziernik 1933 r.

[Polish] This text parallels the German language article in Anwaltsblatt Internationales, as an abbreviated version of the report ‘General (Transnational) Danger‘ he originally presented in French at the 5th Conference for the Unification of Penal Law in Madrid, Spain in October 1933, appeared in the Voice of the Law, legal journal based in Lwow. In publishing this text Lemkin responded to his Polish nationalist critics, who condemned his Madrid Report which was thought to offend Germany at a time when Polish diplomats were negotiating a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, later signed in January 1934.

“O wprowadzenie ekspertyzy kriminalo-biologicznej do procesu karnego” Glos Prawa Lwow: Red A. Lutwak, 1934 no. 3.

[Polish]. Crimino-biological experts in penal procedure, Glos Prawa (The Voice of the Law). This article appeared in March 1934. Itis notable because it identifies the Author as an advocate in private practice, instead of as deputy public prosecutor.

“Le terrorisme. Rapportet Projet de textes.” Actes de la Vme Conference Internationale pour l’Unification du Droit Penal. Madrid. Paris: A. Pedone, 1935; p. 48.

Another version of Lemkin’s October 1933 Madrid report in the official conference proceedings.

“La protection de la paix par le droit penal interne.” Revue Internationale De Droit Penal 15:1 (1938); pp. 95-126.

[French] “Protection of Peace by International Penal Law.” Report presented at the Fourth International Congress of the Association for Penal Law, held in Paris 26-31 July 1938. Lemkin later cited the report on page 55 of his 1944 Axis Rule in Occupied Europe . [check pages 28, 55].

“Revue de jurisprudence at de legislation penale en Polgne” Citta di Castello, Societ’a tipografica “Leonardo da Vinci”; Estratto dalla La Guistizia Penale (Rome) 1938; 24 pp.

[Italian] “Review of Polish Penal Code” City of Castello, Typographical Society’s “Leonardo da Vinci”). Extract from La Guistizia Penale. Beginning in February 1938, Lemkin was listed as a collaborator with this prestigious Italian Legal Journal. Italy began adopting anti-Semitic policies in July of that year.

“Role du juge et sa preparation dans la lutte contre la criminalité” La Giustizia Penale (Rome) 44:1 (October – November 1938), pp. 778-789.

[French] “Role of the judge in the struggle against criminality and its criminological preparation,” a report presented to the First International Congress on Criminology held in Rome, October 1938.

“Verso una convenzione internazionale per la prevenzione e la repressione della falsificazione del passporti unificazione delle incriminazioni” (trad. C. Perris)

[French] “Falsification of Passports as an International Crime: Towards an International Convention for the Protection of Passports.” Report to the Sixth International Conference for the Unification of Penal Law, held in Cairo in January 1938.

“Droit penal en matiere de devises : etude de droit compare” Citta di Castello : Tip. Leonardo da Vinci, 1939, 74 pp.Bibl. di recupero del pregresso, Biblioteca delle Facolta’ di giurisprudenza, lettere e filosofia dell’Universita’ degli studi di Milano

[French]. “The Penal Law for Exchange Restrictions.” A comparative law study, like his French-language book on the same subject La Regulation des Paiements Internationaux, this article was published after the German and Soviet invasions of Poland while Lemkin was a refugee in Lithuania.

“The Legal Framework of Totalitarian Control over Foreign Economies.” Paper (mimeographed), 1941.

[English] Report presented on September 29, 1941in Indianapolis to the American Bar Association’s Section on International and Comparative Law. Lemkin’s paper was not included in the 120 page pamphlet printed before the conference, see Section of International and Comparative Law: Selected Papers and Reports… to be presented at the meeting of the section to be held Sept. 29 – Oct. 1, 1941 (Chicago: American Bar Association, 1941). Lemkin later cited this report in Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, see pages 31, 55, 59, 229, 644. This item is not known to still exist in any library.

“Law and Lawyers in European Subjugated Countries,” Proceedings of the Forty-fourth Annual Session of the North Carolina Bar Association, May 1942, Durham, N.C., 1942, p. 107 -116.

Includes a two-and-half page introduction by North Carolina Bar Association President Willis Smith which includes some biographical details about Lemkin (p. 105-107).

“The Treatment of Young Offenders in Continental Europe.” Law and Contemporary Problems 10:4 (Autumn 1942), pp. 748-759.

Comparative study of educational and correctional measures and juvenile courts in North America and Europe and Soviet Russia. The journal is a publication of Duke University Law School.

“Orphans of Living Parents: A Comparative Legal and Sociological View,” Law and Contemporary Problems, Summer 1944, pp. 834-854.

Paper presented at the Symposium on Children of Divorced parents.

“Copyright Law and the Author in Nazi Germany”, Author’s League Bulletin, Vol. 31, N. 7 (October 1944), p. 15-17.

Discuses how the Nazis used their Reich Chamber of Culture to control literature and intellectual life while leaving German copyright law intact.

“The Legal Case Against Hitler” The Nation, February 24, 1945, p. 205, continued in March 10, 1945, p. 268.

“Genocide – A Modern Crime”Free World (New York), Vol. 9, No. 4, (April 1945), p. 39-43[English] The article summarized for a popular audience the concepts and proposals Lemkin originally presented in Chapter 9 of Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. Free World was a wartime “Non-Partisan Magazine devoted to the United Nations and Democracy,” published in five languages. The article only appeared in the English language edition.

“Genocide” American Scholar, Vol. 15, No. 2 (April 1946), p. 227-230

[English] Lemkin used reprints of this article in English and in French translation extensively at the Nuremberg Tribunal, the August 1946 Conference of the International Law Association in Cambridge, the Peace Conference of minor Axis powers in Paris, and at the second session of the First UN General Assembly in New York at which a Resolution of Genocide was approved on December 11, 1946. Also reprinted as “Genocide”, Answer, No. 4, # 9, Sept. 1946, p. 7-8. See also a recent Spanish translation: “Genocidio” Translation by Carlos Mario Molina Arrubla, August 1999

“Le crime de génocide”La Documentation Francaise, 24 septembre 1946, Notes Documentaires et Etudes No 417 (Serie Textes et Documents. – L), Secrétariat D’Etat a la Présidence du Conseil et a l’Information, Direction de la Documentation 14-16, rue Lord-Byron, Paris (8e), Service d’Information des Crimes de Guerre.

[French] A translation into French of Lemkin’s April 1946 American Scholar article with revisions and additions. Also published in Revue de Droit International, de Sciences Diplomatiques et Politiques 24 (octobre-décember , 1946): 213-222 and Revue Internationale de Droit Pénal 17 (1946): 371-386.

Letter to the editor. New York Times, August 26, 1946.

“Genocide as a Crime under International Law,” American Journal of International Law, Vol. 41, No. 1 (1947), p.145-151

[English] Legal analysis and commentary on the December 11, 1946 General Assembly Resolution.

Letter to the editor. New York Times, February 6, 1947.

Letter to the editor. New York Times, December 20, 1947, p. 8.

Genocide as a Crime under International Law,” United Nations Bulletin, Vol. IV, Jan. 15, 1948

“War Against Genocide; General Assembly of the UN faces problem.” Christian Science Monitor Magazine, Jan. 31, 1948, p. 2; photo.

“Genocide: A Commentary on the Convention.” Yale Law Journal, 58 (June 1949), p. 1142-56.

No author is listed on this article. Lemkin was a contributor.

“Genocide Must Be Outlawed: Only 4 Nations of the 20 Required Have Ratified the UN Convention; Truman is for it, But Senate Hasn’t Acted Yet”, National Jewish Monthly (B’nai B’rith), p. 44

“Senate weighs genocide convention.” Foreign Policy Bulletin 29 (Jan. 20, 1950), p. 2-3.

“My Battle with Half the World,” Chicago Jewish Forum, Winter, 1952.

Letter to the editor. New York Times June 14, 1952, sec. IV, p. 10.

“Is it Genocide?” Anti-Defamation League Bulletin 10:1 (Jan. 1953) 3,8.

A short article (appearing in late January) addressing Communist persecution of Jews in Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union, covering the 1948 anti-cosmopolitan campaign, the 1952 Slatsky Trial in Prague and the January 1953 Doctors Plot in Moscow.

RAPHAEL LEMKIN’S THOUGHTS ON NAZI GENOCIDE Not Guilty? Edited by Steve Jacobs, Edwin Mellon press, Lewiston, New York, 1992, 408pp.

This previously unknown and untitled manuscript by Raphael Lemkin was found among the American Jewish Archives. It is a brilliant summary of those events that culminated in the Nuremberg Trials, from three vantage points: the legal materials, both arguments and evidence; the words of the perpetrators of the Shoah, both before and during the trials, both written and oral; and the words of the victims and survivors. Sections include: “Background”; “Technique” (`Extermination Through Living Conditions’, `Extermination Through Work’,`Torture’, `Sterilization’,etc.); “Intent to Kill”;”The Legal Basis for Nazi Crimes”;”Psychological Reactions”; “Who is Guilty?”‘ and others.

Resources

Benvenuto, J. (2013). Ralph Lemkin Project. Available Online: http://www.ncas.rutgers.edu/center-study-genocide-conflict-resolution-and-human-rights/raphael-lemkin-project-0

Hyde, J. (2008). Polish Jew gave his life defining, fighting genocide. December 10, 2008. Available Online: http://edition.cnn.com/2008/WORLD/europe/11/13/sbm.lemkin.profile/

Lemkin, R. (1933). Acts Constituting a General (Transnational) Danger Considered as Offences Against the Law of Nations. Proposed Text. Available Online: http://www.preventgenocide.org/lemkin/madrid1933-english.htm

Lemkin, R. (1944). Chapter IX: Genocide. In, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation–Analysis of Government–Proposals for Redress. Washington DC, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1944, pages 79-95. Available Online: http://www.preventgenocide.org/lemkin/AxisRule1944-1.htm

UNHCR (2015). Raphael Lemkin, Prominent Refugees. Available Online: http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/search?page=search&docid=3b7255121c&query=genocide%20convention