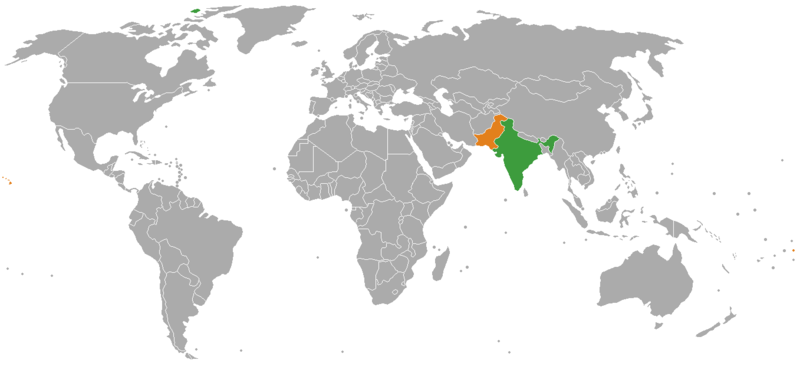

India-Pakistan Relations

In this article, we will discuss the history, and more contemporary issues related to India-Pakistan international relations. We will discuss the tension following the independence of India and then Pakistan, subsequent events and conflicts between the two states, and current conditions. We will also discuss the Kashmir conflict within India-Paksitan relations.

History of India-Pakistan Relations

India and Pakistan are neighbors with a history of tensions between one another. Since the independence of India, and then Pakistan, these two states have been at odds over issues that include the Kashmir conflict. The conflict has not intensified recently, but given that both India and Pakistan have nuclear weapons, any heightened conflict between these two countries is cause for even greater alarm; there have been genuine fears that these two states would possibly fight a nuclear conflict. Therefore, diplomats have worked to reduce India-Pakistan tensions over Kashmir.

India-Pakistan Conflict and Kashmir

Kashmir is a territory between Pakistan and India, and has been a major point of contention in India-Pakistan relations. As India was fighting Britain for self-rule, in the 1930s, a Kashmiri identity was also being established (Carter Center, 2003). Then, following Britain leaving the Indian subcontinent, both India and Pakistan declared independence. However, there were questions about what would be done with the territory known as Kashmir. Muslim, Hindu, and other secular and religious groups all pushed for their own political interests with regards to the future of Kashmir (Carter Center, 2003). Plus, what separated Kashmir from many other areas and prince-controlled areas in India and Pakistan was its location; being between both states led to calls for Kashmir to choose its political affiliation.

Thus, in order to relieve any hostilities over the future Kashmir, the area was able to choose which country that they would be a part of. At the time, the leader of Kashmir was Maharaja Hari Singh, who was a Hindu. Meanwhile the population of Kashmir was primarily Muslim. So, instead of making a politically divisive choice, he chose neutrality (The Telegraph, 2001). However, this position of staying neutral did not last long when, “in October 1947, as Pakistan sent in Muslim tribesmen who were knocking at the gates of the capital Srinagar. Hari Singh appealed to the Indian government for military assistance and fled to India. He signed the Instrument of Accession, ceding Kashmir to India on October 26” (The Telegraph, 2001).

This move of giving Kashmir to India was not without a great amount of controversy. Pakistan and India began a war in 1947 and into 1948 over Kashmir.

Because of this, the United Nations got involved, as India looked to the international organization for aid in stopping the conflict. For example,

“In January 1948, the Security Council adopted resolution 39 (1948), establishing the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) to investigate and mediate the dispute. In April 1948, by its resolution 47 (1948), the Council decided to enlarge the membership of UNCIP and to recommend various measures including the use of observers to stop the fighting” (United Nations, ND).

While the United Nations look to stop the fighting, they also prepared for a vote in Kashmir to decide its future. However, in the meantime, “India, having taken the issue to the UN, was confident of winning a plebiscite, since the most influential Kashmiri mass leader, Sheikh Abdullah, was firmly on its side. An emergency government was formed on October 30, 1948 with Sheikh Abdullah as the Prime Minister. Pakistan ignored the UN mandate and continued fighting, holding on to the portion of Kashmir under its control. On January 1, 1949, a ceasefire was agreed, with 65 per cent of the territory under Indian control and the remainder with Pakistan” (The Telegraph, 2001). This “Line of Control” thus became the line that has divided India and Pakistan (The Telegraph, 2001).

Then, “In July 1949, India and Pakistan signed the Karachi Agreement establishing a ceasefire line to be supervised by the military observers. These observers, under the command of the Military Adviser, formed the nucleus of the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP). On 30 March 1951, following the termination of UNCIP, the Security Council, by its resolution 91 (1951) decided that UNMOGIP should continue to supervise the ceasefire in Kashmir. UNMOGIP’s functions were to observe and report, investigate complaints of ceasefire violations and submit its finding to each party and to the Secretary-General” (United Nations, ND).

In the following years, India began looking to bring Kashmir into their country. They were able to do so in 1957, where Kashmir became a part of India (The Telegraph, 2001).

1965 India-Pakistan War

In 1965, India-Pakistan relations worsened to the point of international conflict. The countries engaged in battle with one another “because of their conflicting claims over the Rann of Kutch at the southern end of the international boundary. The situation steadily deteriorated during the summer of 1965, and, in August, military hostilities between India and Pakistan erupted on a large scale along the ceasefire line in Kashmir. In his report of 3 September 1965, the Secretary-General stressed that the ceasefire agreement of 27 July 1949 had collapsed and that a return to mutual observance of it by India and Pakistan would afford the most favourable climate in which to seek a resolution of political differences” (United Nations, ND). The United Nations Security Council urged a cease-fire between the two states, but both sides expressed conditions. Then, it was not until September 20th that another UN Security Council resolution was passed, and then, two days later, on September 22nd, 1965 in which the cease-fire would commence. The United Nations also increased their role in ensuring the case-fire between India and Pakistan by helping in not only supervising the cease-fire, but also the withdrawal of troops (United Nations, ND).

However, since the cease-fire was not being followed, “The Security Council further demanded the prompt and unconditional execution of the proposal already agreed to in principle by India and Pakistan that their representatives meet with a representative of the Secretary-General to formulate an agreed plan and schedule of withdrawals. In this connection, the Secretary-General, after consultation with the parties, appointed Brigadier-General Tulio Marambio (Chile) as his representative on withdrawals” (United Nations, ND). Then, in January of 1966, the leaders of India and Pakistan met to discuss the cease-fire to the Kashmir conflict. Both sides came away from the meetings saying that they would retreat their troops to positions before August 5th, 1965, and that this should be recognized by February 25th, 1966. The military leaders met again, and confirmed an agreement on both sides to remove troops, which they both did on the 26th of February, 1966 (United Nations, ND).

Kashmir During the 1980s and 1990s

While the two decades prior to the late 1980s saw a more stabilized “status quo” position, the 1980s witnessed Kashmiri calls for determining their own political future. However, the Indian government opposed these calls. Furthermore, hostilities increased further when a 1987 election was fixed. This turned many in Kashmir away from elections, and towards violence. Following the 1987 election, the region saw an increase in jihadist groups. For example, a number of Pakistani based organizations began using violence and terrorism to move the Hindu population out of the Indian Kasmir valley. This led to a military response by the Indian government. All the while, Indian and Pakistani military forces were frequently shooting at one another (The Telegraph, 2001).

India has longed believed that the Pakistani military has encouraged the activity of these groups. Others wonder whether the Pakistani government has any influence over these actors. Nonetheless, the Indian government has often viewed the government as a major problem, frequently going as far as calling Pakistan a “terrorist state” (Carter Center, 2003: 4).

It has been argued that India at this time had no longer been as willing to work through the United Nations compared to 1947 (The Telegraph, 2001). In fact, “Over the decades the plebiscite advocated by India’s great statesman Jawaharlal Nehru became a dirty word in New Delhi. These developments have led many to believe that Delhi has squandered the Kashmiri people’s trust and allegiance” (The Telegraph, 2001).

It was also in the late 1990s that both India and Pakistan were building up their nuclear weapons programs, not only testing bombs (in 1998, for example), but also ensuring that they had missiles capable of carrying the nuclear warheads. It was also during early August of 1998 that the two sides escalated their fighting with one another,

Then, arguably one of the closest periods of a large-scale conflict in the history of India-Pakistan relations came in 1999 in the Kargil area of Kashmir. According to reports,

When India began patrolling the Kargil heights that summer, it found to its horror that many key posts vacated in the winter were occupied by infiltrators. A patrol was ambushed in the first week of May 1999. India belatedly realised the magnitude of the occupation – which was around 10 km deep and spanned almost 100 km of the LOC – and sent MiG fighters into action on May 26.

India contended that the infiltrators were trained and armed by Pakistan, and based in “Azad Kashmir” with the full knowledge of the Pakistani government – and that Afghan and other foreign mercenaries accompanied them.

Pakistan insisted that those involved were freedom fighters from Kashmir and that it was giving only moral support.

It has been argued that Pakistan’s support for the Islamists was because of the new confidence that they had from nuclear weapons (Hoodbhoy & Mian, 2002). It was here that United States President Bill Clinton got involved, meeting with Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in Washington on the fourth of July (The Telegraph, 2001). As Hoodbhoy & Mian (2002) write, “where he was bluntly told to withdraw Pakistani forces or be prepared for full-scale war with India. Bruce Reidel, Special Assistant to President Clinton, writes that he was present in person when Clinton informed Nawaz Sharif that the Pakistan Army had mobilized its nuclear-tipped missile fleet.1 (If this is true, then the preparations for nuclear deployment and possible use could only have been ordered by General Pervez Musharraf at either his own initiative or in consultation with the army leadership.) Unnerved by this revelation and the closeness to disaster, Nawaz Sharif agreed to immediate withdrawal, shedding all earlier pretensions that Pakistan’s army had no control over the attackers.”

It was also on that day that India gained additional territory in Kashmir. The fighting between these two states continued until August of that year. In total it was said that roughly 500 members of the Indian military died, and under 1,000 “infiltrators” (as India, saw them) killed. This conflict was even more worrying given the nuclear power of each state (The Telegraph, 2001). For Pakistan, even though many did not view them on the side of victory during this conflict, for the military, it was a success. The reason was that they were able to keep India within Indian-controlled Kashmir (Hoodbhoy & Mian, 2002).

The Kashmir Conflict Today

Currently, Kashmir is controlled by three countries:

“India-controlled: One state, called Jammu and Kashmir, makes up the southern and eastern portions of the region, totaling about 45% of Kashmir.Pakistan-controlled: Three areas called Azad Kashmir, Gilgit and Baltistan make up the northern and western portions of the region, totaling about 35% of Kashmir.China-controlled: One area called Aksai Chin in the northeastern part of the region, equaling 20% of Kashmir” (Hunt, 2016).

India-Pakistan Relations and Nuclear Weapons

Improving India-Pakistan Relations

Given the state of conflict between these two countries, scholars and policymakers have long posited options for improved ties between India and Pakistan. Some have long argued that a reduction of nuclear weapons would be one positive step in ensuring that a major conflict with such devastating tools would not be possible. Others have suggested that cooperation is what is necessary not only to prevent a war, but also to build strong states and institutions. The Carter Center (2003) has argued that positive cases between India and Pakistan can provide a path to further cooperation initiatives; “Energy trade is one area of considerable promise. India could consume as much energy as it could receive from any and all of its neighbors. Energy relationships create dependency relationships, almost by definition. And India and Pakistan’s experience with the Indus Water Treaty is one of the rare positive examples of prudence and creativity in the otherwise troubled bilateral relationship” (4).

The Carter Center (2003) also argues for continued diplomacy. For them, it is important that conversations continue, even when violence breaks out. They recognize that by giving into the violence, it will allow “spoilers” to dictate the direction of policy on Kashmir. In the talks, it is also imperative for compromise (Carter Center, 2003). Moreover, it has been argued that the United States has a role in helping to improve India-Pakistan relations. The US has had a long history of ties with Pakistan–as far back as the Cold War, although there have been US concerns about Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program) (Kronstadt, 2006), and despite political challenges between India and the United States during the Cold War, there has exited a far improved relationship following the fall of the Soviet Union (Kronstadt & Pinto, 2013).

Scholars and those in policy alike argue there is a lot that the United States can do to help both India and Pakistan. They can be a key actor in improving relations between the two states. For example, “Formal bilateral confidence-building measures (CBMs) agreed upon at the official and unofficial levels can help effect a new process by setting into place the building blocks for an eventual agreement, targeting substantive issues such as reducing and removing troops from uncontested areas and implementing technical safeguards to monitor infiltration. These safeguards would likely include sensor technology, provided by the United States to both Pakistan and India, to make the Line of Control harder to cross by militants. Technological deployment of this kind would likely require coordination by both India and Pakistan and would build confidence by demonstrating a concrete commitment by Pakistan to act assertively on infiltration and a willingness by both parties to work together in resolving this contentious issue” (7).

India-Pakistan Relations in 2017

References

Ahmad, M., Phillips, R. & Berlinger, J. (2016). Uri attack: Indian soldiers killed in Kashmir. CNN. September 19, 2016. Available Online: http://edition.cnn.com/2016/09/18/asia/india-kashmir-attack/

Ahmed, I. (2016). Pakistan impregnable, military insists after Kashmir ‘raid’. Yahoo News. October 2nd, 2016. Available Online: https://www.yahoo.com/news/pakistan-impregnable-military-insists-kashmir-raid-072700959.html

Busvine, D. & Pinchuk, D. (2016). UPDATE 1-India’s Modi, at summit, calls Pakistan “mother-ship of terrorism”. Reuters. In CNBC. October 16, 2016. Available Online: http://www.cnbc.com/2016/10/16/reuters-america-update-1-indias-modi-at-summit-calls-pakistan-mother-ship-of-terrorism.html

Carter Center (2003). The Kashmiri Conflict: Historical and Prospective: Intervention Analyses. The Carter Center. November 19-21, 2002. Available Online: https://www.cartercenter.org/documents/1439.pdf

Hindustan Times (ND). When India almost went to war with Pakistan. Hindustan Times. Available Online: http://blogs.hindustantimes.com/inside-story/2011/11/02/when-india-went-to-war-with-pakistan-twice/

Hoodbhoy, P. & Mian, Z. (2002). The India-Pakistan Conflict: Towards The Failure of Nuclear Deterrence. Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability. November 13, 2002. Available Online: http://nautilus.org/napsnet/special-policy-forum-911/the-india-pakistan-conflict-towards-the-failure-of-nuclear-deterrence/

Hunt, K. (2016). India and Pakistan’s Kashmir dispute: What you need to know. CNN. September 30, 2016. Available Online: http://www.cnn.com/2016/09/30/asia/kashmir-explainer/index.html

Hussain, A. (2016). Anti-India clashes erupt in Kashmir city after boy’s killing. The Washington Post. October 8, 2016. Available Online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/rebels-attack-police-post-in-kashmir-killing-policeman/2016/10/07/b33909c2-8d04-11e6-8cdc-4fbb1973b506_story.html

Kronstadt, A. (2006). Pakistan-US Relations. CRS Issue Brief for Congress. March 6, 2006. Available Online: http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IB94041.pdf

Kronstadt, A. & Pinto, S. (2013). U.S.-India Security Relations: Strategic Issues. Congressional Research Service. January 24, 2013. Available Online: https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R42948.pdf

NPR (2008). Fears Of India-Pakistan Nuclear War Raged In 2002. NPR. All Things Considered. December 18, 2008. Available Online: http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=98443922

Roychowdhury, A. (2016). Here is a history of India-Pakistan conflict. The Indian Express. September 29, 2016. Available Online: http://indianexpress.com/article/research/here-is-a-history-of-india-pakistan-conflict/

Shrivastava, R. (2016). 100 Terrorists At Launch Pads Near Line of Control, PM Narendra Modi Is Told. NDTV. October 5, 2016. Available Online: http://www.ndtv.com/india-news/nearly-100-terrorists-waiting-to-cross-line-of-control-pm-modi-is-told-1470433?pfrom=home-lateststories

The Telegraph (2001). A brief history of the Kashmir conflict. The Telegraph. 24 September 2001. Available Online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/1399992/A-brief-history-of-the-Kashmir-conflict.html

United Nations (ND). India-Pakistan Background. Available Online: http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/past/unipombackgr.html

Voice of America (2016). Pakistan Will Meet Indian Aggression in Kashmir with ‘Most Fitting Response.’ Voice of America (VOA). October 6, 2016. Available Online: http://www.voanews.com/a/pakistan-will-meet-indian-aggression-in-kashmir-with-most-fitting-response/3539437.html