Non-Aligned Movement

In this article, we will discuss the term “non-aligned movement.” This is an important organization, particularly in the history of international relations, and especially as it pertains to the Cold War period. Understanding the Non-Alignment Movement, and its positions on key international relations issues will be useful for those looking to know more about how a large country bloc has attempted to work together on issues such as nuclear disarmament, the politics of Global South states, as all as for those who want to know more about international organizations, or the history of international relations as it pertains to the Cold War.

Non-Aligned Movement Definition

The non-aligned movement was a movement of countries during the Cold War that decided they did not want to align either with the United States (and their allies), nor with the Soviet Union and their allies.

History of the Non-Aligned Movement

The history of the Non-Aligned Movement officially began in 1961 in what is now the Former Yugoslavia. In fact, “The first Conference of Non-Aligned Heads of State, at which 25 countries were represented, was convened at Belgrade in September 1961, largely through the initiative of Yugoslavian President Tito. He had expressed concern that an accelerating arms race might result in war between the Soviet Union and the USA.” There were 25 states in attendance at the first official Non-Aligned Movement conference. The states present were: “Afghanistan, Algeria, Yemen, Myanmar, Cambodia, Srilanka, Congo, Cuba, Cyprus, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Lebanon, Mali, Morocco, Nepal, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Yugoslavia” (MEA.gov.in, 2012).

However, while the first conference under the Non-Aligned Movement took place in 1961, it has been argued that the roots of the Non-Aligned Movement can be traced back to the year 1955. It was then that the Bandung Conference (also referred to as the Asian-African Conference) that a number of states spoke out about their “neutral” position as it related to the Cold War. At that time, the United States and the Soviet Union were looking to expand their influence in the world (while ensuring the other was not doing the same). However, there were 29 countries from Africa and from Asia that wanted to state they were not going to be tied or aligned with either the US or the USSR.

It was also at the 1955 Bandung Conference that these states “Adopted a 10-point “declaration on the promotion of world peace and cooperation,” based on the UN Charter and the Five Principles of Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.”Thus, it is important to note the contribution and public statement of countries in 1955, as well as the organizing role of Josep Tito for the Non-Aligned Movement. in 1961. The Ten Principles were:

1. Respect for fundamental human rights and for the purposes and the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

2. Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations.

3. Recognition of the equality of all races and of the equality of all nations large and small.

4. Abstention from intervention or interference in the internal affairs of another country.

5. Respect for the right of each nation to defend itself singly or collectively, in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations.

6. Abstention from the use of arrangements of collective defense to serve the particular interests of any of the big powers, abstention by any country from exerting pressures on other countries.

7. Refraining from acts or threats of aggression or the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any country.

8. Settlement of all international disputes by peaceful means, such as negotiation, conciliation, arbitration or judicial settlement as well as other peaceful means of the parties’ own choice, in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations.

9. Promotion of mutual interests and cooperation.

10. Respect for justice and international obligation.

In fact, “In aggregating political and economic demands – the twin strategy of the movement – for the final salvation of the destitute nations, the Charter principles of sovereignty, territorial integrity, non-interference and multilateralism form the Holy Grail on which reforms in international relations are pursued. In all summit documents these principles assume such prominence and are repeated so often in relation to different subject-matters, that the impression is hardly avoidable that there lurks a deeper motivation for their over-reiteration than a deep-seated political and moral conviction about their relevance for international relations” (Strydom, 2007: 4).

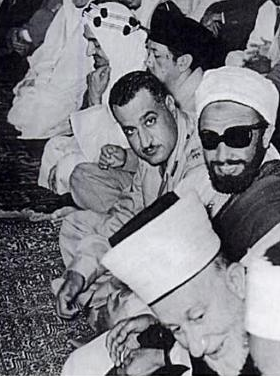

Then, in 1960, “…in the light of the results achieved in Bandung, the creation of the Movement of Non-Aligned Countries was given a decisive boost during the Fifteenth Ordinary Session of the United Nations General Assembly, during which 17 new African and Asian countries were admitted. A key role was played in this process by the then Heads of State and Government Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Shri Jawaharlal Nehru of India, Ahmed Sukarno of Indonesia and Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia, who later became the founding fathers of the movement and its emblematic leaders” (MEA.gov.in, 2012).

As mentioned, the 1955 conference, the 1960 activities in the United Nations General Assembly, and the 1961 Non-Aligned Movement conference in Yugoslavia were central meetings for the formation of the NAM, where these principles for articulated in much detail. But they were not the only meetings of the Non-Aligned Movement.

Along with these two conferences, the Non-Aligned Movement continued to meet in the following years, and worked to further these principles that were stated years prior. For example, after the initial conference in Yugoslavia during the heightened and tense period of the Cold War, “Subsequent conferences involved ever-increasing participation by developing countries. The 1964 Conference in Cairo, with 47 countries represented, featured widespread condemnation of Western colonialism and the retention of foreign military installations. Thereafter, the focus shifted away from essentially political issues, to the advocacy of solutions to global economic and other problems” (Government of South Africa, 2001: NAM.Gov.za). For example, here is a list of Non-Aligned Movement conference beginning during the Cold War, until roughly a handful of years following the Cold War.

- First Conference – Belgrade, September 1-6, 1961

- Second Conference – Cairo, October 5-10, 1964

- Third Conference – Lusaka, September 8-10, 1970

- Fourth Conference – Algiers, September 5-9, 1973

- Fifth Conference – Colombo, August 16-19, 1976

- Sixth Conference – Havana, September 3-9, 1979

- Seventh Conference – New Delhi, march 7-12, 1983

- Eighth Conference – Harare, September 1-6, 1986

- Ninth Conference – Belgrade, September 4-7, 1989

- Tenth Conference – Jakarta, September 1-7, 1992

- Eleventh Conference – Cartagena de Indias, October 18-20, 1995 (Government of South Africa, 2001).

Along with these conference during and shortly after the Cold War, the Non-Aligned Movement has continued to meet on a yearly basis for its Non-Aligned Movement Summit that has been hosted in different countries; the organization still has a presence in international affairs today. These Non-Aligned Movement Summits are held every three years. The 2009 Non-Aligned Movement Summit was held in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, 2012 Non-Aligned Movement Summit was held in Iran, and the 2015 Non-Aligned Movement Summit was held in Venezuela.

Central to the Non-Aligned Movement for the early meetings, and through the Cold War were the emphasis on independence, freedom from outside interference from other countries, decolonization, as well as challenging other forms of oppression such as colonialism and any abusive types of political systems (Inventory of International Nonproliferation Organizations and Regimes, 2012).

Members of the Non-Aligned Movement

As of the year 2012, there have been 120 member states within the Non-Aligned Movement. These states are:

NAM Membership: 120 Members (July 2011) – Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Antigua and Barbuda, Azerbaijan, Bahamas, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belarus, Belize, Benin, Bhutan, Bolivia, Botswana, Brunei Darussalam, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Chile, Colombia, Comoros, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Cuba, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), Democratic Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Fiji, Ga- bon, Gambia, Ghana, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Jamaica, Jordan, Kenya, Kuwait, Lao Peoples’ Democratic Republic, Lebanon, Lesotho, Liberia, Libyan Arab Jamahirya, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mali, Mauritania, Mau- ritius, Mongolia, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Qatar, Rwanda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Sao Tome and Principe, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Somalia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Suriname, Swazi- land, Syrian Arab Republic, Tanzania, Thailand, Timor Leste, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Uganda, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Vietnam, Yemen, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Observer States: Argentina, Armenia, Bosnia- Herzegovina, Brazil, China, Costa Rica, Croatia, El Salvador, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mexico, Montenegro, Paraguay, Serbia, Ukraine, Uruguay.Observer Organizations: African Union, Afro- Asian People’s Solidarity Organization, Kanak Socialist National Liberation Front, League of Arab States, New Movement for the Independence of Puerto Rico, Organization of the Islamic Conference, South Center, United Nations, Secretariat of the Commonwealth Nations, World Peace Council.

To be a member of the Non-Aligned Movement meant that you did not have an interest in aligning with one of the superpowers during the Cold War. But along with that, there was also an expectation that countries placed importance on decolonization and self-determination. However, like many issues in international relations, to suggest that the leaders of countries showed no favoritism towards one of the superpowers would be inaccurate. As Strydom (2007) explains, while “…non-alignment meant the rejection of control by the superpowers of the time and the adoption of a foreign policy stance that implied resistance against East–West pressures and solidarity with Third World interests relating to strategic world political and economic issues. Non-alignment in this sense should not be taken too literally though: some members at the time had difficulty in hiding their ideological preferences, and development aid – with the normal strings attached – has the unavoidable tendency to effect changes in allegiances” (2).

This is an important note. The Cold War politics drove the USSR and US to vie for political allies, and they were often willing to pay a high political and economic price for such relationships. This might have meant billions of dollars in military and development aid, or a willingness to turn their heads away from blatant human rights abuses by regimes in which they were looking to ensure favor and allegiance.

Decision-Making in the Non-Aligned Movement

One of the interesting facets of the Non-Aligned Movement as an international organization is its organizational and voting structure. While many international organizations have official constitutions, the Non-Aligned Movement does not. Furthermore, there is no Secretariat representing the NAM. Moreover, “its administration is non-hierarchical and rotational. Decisions are made by consensus, which requires substantial agreement, but not unanimity” (Inventory of International Nonproliferation Organizations and Regimes, 2012). This sort of structural mechanism shows how the Non-Aligned Movement attempted to offer an equal vote to all members, something that has been traditionally a core criticism of other international organizations such as the United Nations (namely, with regards to the powers of the United Nations Security Council).

The Non-Aligned Movement does have working groups, task forces, contact groups, etc… to deal with the various issues that the NAM is discussing and dealing with among its member states. Such entities within the organization include the “NAM High-Level Working Group for the Restructuring of the United Nations; NAM Working Group on Human Rights; NAM Working Group on Peace-Keeping Operations; Ministerial Committee on Methodology; NAM Working Group of the Coordinating Bureau on Methodology; NAM Working Group on Disarmament; Committee of Palestine; Contact Group on Cyprus; Task Force on Somalia; Task Force on Bosnia and Herzegovina; Non-Aligned Security Council Caucas; Coordinator Countries of the Action Program for Economic Cooperation; and the Standing Ministerial Committee for Economic Cooperation” (Inventory of International Nonproliferation Organizations and Regimes, 2012).

Key Issues of the Non-Aligned Movement

While the Non-Aligned Movement spend much of the Cold War focused on issues of decolonization, self-determination, human rights and development, one of the core issues that the organization concentrated much of its efforts on was the issue of disarmament. The discussion of disamarment was not solely limited to the Cold War; this was an issue that was being discussed in great detail for decades prior. However, with the issues of bipolarity in the world at the time (and the arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union), along with the new concern of nuclear weapons, the Non-Aligned States found it necessary to address the issue of weapons in the international system. Thus, much of the discussion was at least partly driven by political developments between Cold War powers, but also developments in the United Nations (within both the UN General Assembly, as well as the UN Security Council). However, while there were initial attempts in the 1950s for managing arms, this was not viewed as successful. And as a result, “the international debate moved from general and complete disarmament, the all or nothing approach, to attainable arms control accomplishments.

This new phase in disarmament negotiations also provided the prelude to a preference for bilateral treaty arrangements on arms control,25 both nuclear and conventional, between the superpowers which succeeded in wrestling the debate from the multi-lateral process in the General Assembly where the enthusiasm for general and complete disarmament was still high” (Strydom, 2007: 9). For the Non-Aligned Movement, the issue of disarmament was one of great importance; they viewed a peaceful world being one without these weapons, and thus, attempted to work towards some sort of agreement to limit arms in the international system. This idea of nuclear disarmament was a common thread for the various NAM summits.

Moreover, they also called for a more equal system of non-nucleaar weapons. They recognized (and were concerned with) gross power imbalances in the international system, and thus, were critical of Global North states that attempted to limit the ability of the Non-Aligned Movement states to receive weapons (Strydom, 2007).While they wanted reduced weapons, their position towards this new balance of weapons was centered on a notion of establishing “international peace and security” (Strydom, 2007: 12) (This position has been criticized by some. For example, Strydom, 2007 writes that “It is one thing to aim at restoring imbalances in military power, but quite another to believe that a more equal spread in arms manufacturing and acquisition capacity will somehow be more immune to the dark re- alities of the arms industry; and downright naïve to think that the resto- ration of a balance of military power by agreement will reduce consumer-dominated interest in new markets and prevent a rush to new al- liance formation for strategic purposes” (12). Lastly, the Non-Aligned Movement’s position was to reduce small arms in the global system (even though, even here, a criticism was that states themselves were at times responsible for perpetuating the sales of weapons) (Strydom, 2007).

The Non-Aligned Movement and the United Nations

One of the other issues that the Non-Aligned Movement has been known for is its attention towards reforming the United Nations. More specifically, NAM has been concerned about international development among its member states, and what the United Nations can do to successfully implement development policies. But much of their issues with the United Nations as it pertains to development begins with their criticism of the structure of the United Nations, and especially the imbalanced power of the Security Council. They continue to advocate for additional General Assembly and ECOSOC power, and in turn to limit the ability of the Security Council to expand their influence into areas historically acted upon by the General Assembly. They have not only challenged the Security Council’s inaction towards various rights abuses (such as responding to cases of genocide), but the NAM would like the General Assembly to have a stronger voice on international security issues (Strydom, 2007), which continue to be dominated by the powers at the UNSC (as they have the ability carry out sanctions, military forces, or peacekeepers (through Chapter VII) (for a discussion on United Nations reform, feel free to read our article on the United Nations here).

The United Nations leadership has continued to work with the Non-Aligned Movement on international issues. For example, in 2012, Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon spoke to the NAM Summit in Iran. Here, he spoke highly of the organization, and stressed the important role that they play in the United Nations, and in international peacekeeping operations.

The Non-Aligned Movement Today

Given the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement during the Cold War, there have been questions about the usefulness of continuing the international organization given the fall of the Soviet Union. Namely, “By the end of the 1980s, the Movement was facing the great challenge brought about by the collapse of the socialist block. The end of the clash between the two antagonistic blocks that was the reason for its existence, name and essence was seen by some as the beginning of the end for the Movement of Non-Aligned Countries” (MEA.gov.in, 2012).

Rasool & Pulwana (2013) suggest that there are a number of reasons to think that the Non-Aligned Movement no longer serves the same function and importance as it did decades prior. They argue that the NAM not only is unable to establish a significant amount of domestic capital investment within their countries, but that the NAM is also stuck on historical policies of leaders such as Gamal Abdel Nasser, positions that are not as effective today. Moreover, with a host of other international organizations, there is a belief that the Non-Aligned Movement is repetitive. There are also criticisms that the Non-Aligned Movement does not have strong consistent leadership who can unite the different countries, nor does the NAM have a strong record of accomplishments on many international issues.

However, they also argue there are many reasons to think that the Non-Aligned Movement continues to have relevance in the international relations of today. One issue where the NAM can continue to work effectively is on disarmament. With the continued conflicts in the world, and the increasing number of weapons, having an organization that advocates for not only a reduction of weapons, but also a better balance could be much needed. Furthermore, NAM countries continue to be active in the United Nations, in which they advocate for issues that are important to the Non-Aligned Movement. Moreover, there are many issues that are of the utmost importance to Non-Aligned Movement states that are as important today as they were in decades past; the US’ role as a dominant power, issues of corruption, human rights, as well as the need for continued international cooperation between Non-Aligned Members and other countries is quite pressing today (Rasool & Pulwana, 2013).

Conclusion

In this article, we have introduced the Non-Aligned Movement, have discussed its history (as it pertains to the politics of the Cold War), the formation of the organizations, its membership, issues of importance to the NAM, and we have also discussed the question about the necessity of the international organization in international political today. The Non-Aligned Movement is clearly an organization that has a rich history in international relations, and continues to speak on a host of issues in international affairs.

References

Government of South Africa (2001): The Non-Aligned Movement: Background Information. Available Online: http://www.nam.gov.za/background/background.htm#1.1%20History

Inventory of International Nonproliferation Organizations and Regimes (2012). Non-Aligned Movement. James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Available Online: http://cns.miis.edu/inventory/pdfs/nam.pdf

MEA (Minister of Exterior Affairs) (2012). History and Evolution of Non-Aligned Movement. August 22nd, 2012. Available Online: http://mea.gov.in/in-focus-article.htm?20349/History+and+Evolution+of+NonAligned+Movement

Rasool, A. & Pulwana, A. (2013). Non-Aligned Movement in 21st Century: Relevant or Redundant?…A Debate. IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), Vol. 11, Issue 4, pages 64-70. Available Online: http://iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol11-issue4/I01146470.pdf?id=6311

Strydom, H. (2007). The Non-Aligned Movement and the Reform of International Relations. Available Online: http://www.mpil.de/files/pdf1/mpunyb_01_strydom_11.pdf

United Nations (2012). Non-Aligned Movement’s Role at United nations Will Remain Crucial as it Continues to Define Evolving Identity, Security-General Tells Group’s Summit. United Nations Secretary-General Press Release. SG/SM/14481. 30 August 2012. Available Online: http://www.un.org/press/en/2012/sgsm14481.doc.htm