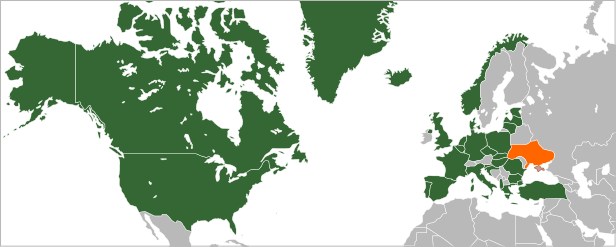

NATO and Ukraine

In this article, we shall discuss the relationship between the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and Ukraine, particularly regarding Russia’s support for the annexation of the Crimea, and their current willingness to back separatist rebels in eastern Ukraine. In this article, we shall discuss the different international relations issues regarding the Ukrainian conflict, and the role NATO is playing. More specifically, we shall examine NATO’s positions towards Ukraine and Russia, and the implications of NATO allowing Ukraine to enter the international organization.

The Ukraine conflict began in 2014 when Russia backed separatists in the Crimea and in Eastern Ukraine. However, “[t]he roots of the crisis lie in the 2008 war between Russia and Georgia, which ended the prospect of enlargement of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) for both Georgia and Ukraine, and in the beginning of the global financial crisis, which seemed to give more credence to regional economic arrangements. Then, the EU and Russia drew different conclusions from the war and the crisis. The Europeans, through the Eastern Partnership program the EU launched in 2009, looked to associate Ukraine, along with five other former Soviet republics, economically and politically with the EU. Rather than a step toward future EU enlargement, however, this initiative was an attempt to constitute a “zone of comfort” to the east of the union’s border and enhance these countries’ Western orientation” (Trenin, 2014). For Russia, they looked to the former Soviet states to build an economic alliance in an attempt to counter countries and actors such as China as well as the European Union (Trenin, 2014).

Thus, the political leadership under Viktor Yanukovych was receiving economic interest from both Europe and also Russia. Europe offered Yanukovych an economic deal, but he pulled out of the talks, and instead, in November 2013, turned to Moscow for support. He was rewarded by a significant economic deal, both in terms of keeping the low tariffs, and also receiving aid from Russia. However, his reverse on the European economic deal quickly led to protests in Kiev. With regards to the protests, “Most protesters were ordinary people who suffered from poverty and were deeply incensed by runaway official corruption, including in Yanukovych’s family. To those people, EU association appeared as a way out of this undignified situation, and the abrupt and unexpected closure of that door produced a painful and powerful shock” (Trenin, 2014: 5).

The political situation then became a battle for the direction of Ukraine, with protesters largely calling for a closer relationship with Europe, and the government, under Yanukovych, being viewed as aligning themselves, and the future of the country with Russia (Trenin, 2014). Following fighting in Kiev, Yanukovych agreed to leave the country, which appeased protesters, but angered Russia. As Trenin (2014) notes, “to most Russians, the country was anything but foreign. Now, Ukraine was suddenly turning into a country led by a coalition of pro-Western elites in Kiev and anti-Russian western Ukrainian nationalists. This shift, in the Kremlin’s eyes, carried a dual danger of Kiev clamping down on the Russian language, culture, and identity inside Ukraine and of the country itself joining NATO in short order. Putin reacted immediately by apparently putting in motion contingency plans that Moscow had drafted for the eventuality of Kiev seeking membership in the Atlantic alliance” (6).

What is NATO?

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) is an international organization formed following World War II, bringing together the United States and allies as a military alliance, primarily against the Soviet Union and their allies. Throughout the decades, NATO worked to ensure that Soviet expansion was not taking place. Following the end of the Cold War, NATO has continued to exist as a military alliance.

History of NATO and Ukraine

Ukraine is not a member of NATO. However, NATO and Ukraine have been building a relationship since the fall of the Soviet Union. After the end of the Cold War, a number of Soviet areas declared independence from then Russia. One of the states was Ukraine, establishing independence in 1992. Months after this announcement, “NATO invited its representative to an extraordinary meeting of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council, the forum bringing together NATO and the states of the former Warsaw Pact. All participants in the meeting declared their determination to “work together towards a new, lasting order of peace in Europe through dialogue, partnership, and cooperation”” (NATO, 2015). Then, in 1994, NATO established a program called “Partnership for Peace” which aimed to build ties amongst NATO countries and others. Ukraine joined the this program in February of 1994. Following this, Ukraine began working with NATO states by sending some of their troops to help with the situation in Bosnia (NATO, 2015).

Following this, as NATO (2015) notes, “On 9 July 1997, NATO and Ukraine signed a charter establishing a distinctive partnership. The Charter set out a wide range of areas for potential cooperation, including civil emergency planning, military training and environmental security. It established the NATO-Ukraine Commission where NATO Allies would regularly work with Ukraine to develop deeper cooperation. After signing the Charter, cooperation proceeded quickly: NATO established trust funds to help dispose of toxic waste and to retrain former military officers, advised Ukraine on reform and democratic oversight of the defence and security forces and invited it to participate in NATO-led exercises. Ukraine contributed forces to the NATO-led missions in Afghanistan and Kosovo.”

In the years after, there was (and continues to be) a push by actors in Ukraine to join NATO. For example, in May, 2002, the President of Ukraine at the time Leonid Kuchma spoke about the desire for Ukraine to enter into NATO. Then, the foreign ministers of NATO began focusing more on the possibility of Ukraine entering into the international military organization, and spoke about reforms that Ukraine should make. Then, in the years that followed, NATO and Ukraine increased their military partnerships through “signing[ing] an agreement on the provision of strategic airlift, and established trust funds to dispose of excess munitions and small arms.”

In 2008 during the NATO Summit in Bucharest, NATO spoke positively about Ukraine’s (and also Georgia’s) desire for entrance into the organization. A statement made said that ““NATO welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO. We agreed today that these countries will become members of NATO. Both nations have made valuable contributions to Alliance operations. We welcome the democratic reforms in Ukraine and Georgia”” (NATO, 2015). However, as we shall discuss below, NATO moved away from this idea in 2010, but Ukraine still helping with military support to the organization (NATO, 2015).

NATO and the Ukraine Crisis

Following the removal of Yanukovych from power, Russia became concerned that Ukraine would move further and further away from Moscow, and not only aligning themselves with Europe economically, but possibly also joining NATO (Trenin, 2014). Not wanting any of this to happen, beginning in March 2014, Russia began supporting separatist forces in the Crimean Peninsula. They then also backed (and still back) separatists in Eastern Ukraine, arguing that they wanted to protect Russian speaking minorities in the country (Trenin, 2014). Thus, “When Russia launched its illegal military action against Ukraine, the North Atlantic Council met in emergency session to discuss the implications. On 2 March 2014, the Council stated that “NATO Allies will continue to support Ukrainian sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity, and the right of the Ukrainian people to determine their own future, without outside interference,” and agreed that “military action against Ukraine by forces of the Russian Federation is a breach of international law and contravenes the principles of the NATO-Russia Council and the Partnership for Peace.” The same day, they held an emergency session of the NATO-Ukraine Commission” (NATO, 2015).

Then, in September 2014, NATO leadership gave a statement on their support for the sovereignty of Ukraine, and in this statement, they also condemned Russia for annexing the Crimea. In the later months, NATO continued to repeat the same message of support for Ukraine, all the while maintaining their position that Russia’s actions were a violation of international law and the sovereignty of Ukraine. In 2015, NATO was involved in a series of actions to help support Ukraine. As the international organization notes,

Allies are continuing to strengthen cooperation with Ukraine as it pursues deep and comprehensive reforms, including through its Annual National Programme (ANP). The NATO Foreign Ministers, meeting on 13 May 2015, welcomed the steps Ukraine has taken in promoting key constitutional reforms and reconciliation. They encouraged the Ukrainian Government to continue and accelerate reform efforts.

In response to the conflict, NATO has also significantly stepped up its practical assistance to Ukraine. Immediate actions help Ukraine address the current conflict, and long-term measures build capacity, develop capabilities and contribute to a deep reform of the armed forces and security sector.

At the Wales Summit, Allies agreed to establish a series of concrete measures, including Trust Funds, to help Ukraine strengthen its ability to defend itself. The Trust Funds provide support in the areas of Logistics and Standardization; Command, Control, Communications and Computers; Cyber Defence; Military Career Management; Medical Rehabilitation. Extensive work is underway to implement the first Trust Funds projects.

The conflict in the Ukraine continues. As of August 2016, the conflict has taken the lives of over 9500 people.

Tensions between the two countries have risen in recent months. Ukraine has moved troops to the border of the Crimea, which has lead to a rebuke from Russian leader Vladimir Putin. Throughout the conflict, Russia has continued to be a staunch backer of the separatists in the Crimea and eastern Ukraine, giving them weapons, military training, and also at times themselves being seen in the country.

There is a belief that Russia continues to have goals of taking over more territory in western Ukraine, and also in Eastern Ukraine, if given the opportunity. Some argue that this interest stems from feels of resentment of Ukraine breaking away following the end of the Cold War and the Soviet Union. For example, Dibb argues that for Putin, the breakup of the Soviet Union, and the independence of these many former Soviet states was a tragedy; “Putin saw it as Russia not ‘only being robbed, but plundered'” (Killalea, 2016).

Others, such as Stephen Blank, who is a senior fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council, argued that ““Russia wants to punish Ukraine for moving toward NATO, and they want to make clear to NATO that they can take Ukraine any time they want,” Blank said. “Russia’s policy is to try to force Ukraine to fall apart”” (Peterson, 2016).

While Russia began its cooperation with NATO following the end of the Cold War, this changed in 2007, when Putin spoke about NATO enlargement as a threat to Russian security. Putin has also been concerned about a US missile defense system in the European continent (Sabitov, 2014). However, it has been this NATO enlargement that seems to be a key issue for Russia; “In 1999, Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic joined the organization, in 2004 with the accession of seven Central and Eastern European countries: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania. Albania and Croatia joined on 1 April 2009” (Sabitov, 2014: 2), all of which seemed to lead to further tension between Russia and the international organization.

For the West, the end of the Cold War brought about US hegemony. However, “For [Putin], the end of the Cold War and the breakdown of the Soviet Union was a defeat for Russia rather than a victory for democracy over communism. In March 2014, 63 per cent of Russians agreed with the president that Russia had regained its status as a superpower according to an opinion poll conducted by the Russian Levada Centre, which could also report that 80 per cent of Russians approved of Putin’s policy” (Rasmussen et. al., 2014: 12). But for Russia, it was the NATO expansions, along with US actions in Iraq (without regard for international opposition), and its support of Kosovo’s independence from Serbia in 2008 (Rasmussen et. al., 2014) that only elevated Russia’s frustration with the new power relations in the world.

NATO Support for Ukraine

NATO countries have continued to supportUkraine different ways. For example, they have been providing Ukraine weapons. For example, “In June [of 2014], Secretary General Rasmussen announced the creation of several new NATO trust funds to help develop Ukrainian defense capacity, including in the areas of logistics, command and control, cyber defense, and assisting retired military personnel to adapt to civilian life” (Belkin et. al, 2014).

Furthermore, military leaders from countries such as the United States of America have been aiding Ukraine in military simulations. These more recent joint military exercises have been going on for a couple of years.

NATO has also helped with patrols, and also air surveillance. However, NATO countries have not been willing to give Ukraine military weapons, nor have they stationed permanent troops in the country (Belkin et. al, 2014).

In 2014, United States President Barack Obama called for Congress to approve over 1 billion dollars towards the “European Reassurance Initiative” which would help allies in Europe by easing concerns and building defense capabilities (Belkin, Mix, & Woehrel: 2014: 5). This initiative is to focus on five specific areas, which are:

- Increased U.S. military presence in Europe ($440 million). Could include augmented U.S. Army rotations to the NATO Response Force (NRF); enhanced F-15 fighter jets deployments and increased participation in NATO’s Baltic Air Policing mission; expanded naval presence in the Baltic and Black Seas; and expanded Marine rotations through the Black Sea Rotational Force in Romania.

- Improved infrastructure to allow for greater military responsiveness ($250 million). Could include improvements to air fields and training ranges and operations centers in Central and Eastern Europe. Improvements would require agreement from host nations.

- Enhanced prepositioning of U.S. equipment in Europe ($125 million). Activities could include adding U.S. air equipment in Eastern Europe; and improved prepositioning facilities for Marine equipment in Norway.

- More extensive U.S. participation in military exercises and training with allies and partners ($75 million). Could include increased U.S. force levels in military exercises in Europe, as well as funding to enable enhanced allied and partner participation in such exercises. The exercises aim to improve allied and partner readiness and interoperability.

- Intensified efforts to build military capacity in newer NATO members and partner countries ($35 million, in addition to $75 million from Department of State). Activities could focus on building military capacity in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine. Areas of emphasis include filling critical operational gaps in border security and air and maritime awareness and strengthening civilian oversight of the defense establishment (Belkin, 2014: 5).

The European Reassurance Initiative is now upwards of 3.4 billion dollars (the figure requested for the 2017 budget in the United States) (Moon Cronk, 2016) to help American allies shore up their defense (Shaheen, 2016).

Along with these developments, during the summer of 2016, NATO countries met in Warsaw Poland to talk about ways that the can build up their defense and also respond to Russian actions in the western part of Ukraine. As reported in July, “In a joint press conference with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg on Saturday evening, Poroshenko praised NATO’s approval of a comprehensive assistance package to bolster Ukraine’s military capabilities—including interoperability with NATO forces—and to accomplish key reforms. While Stoltenberg said full NATO membership for Ukraine was “not currently on the table,” Poroshenko called Ukraine’s relationship with NATO a “de facto alliance”” (Peterson, 2016).

Would Ukraine Become a Member of NATO?

While the comments from NATO members suggest that a strong alliance exists between NATO and Ukraine, many believe that the odds of the international organization accepting Ukraine as a member of NATO is highly unlikely. The reason? Such an action will surely be viewed with disgust from Russia, and may lead to a severe increase in hostilities, and possibly even a war.

As mentioned, for Russia, the issue of NATO expansion has been a rather problematic one. They have questioned the necessity of NATO existing, since it was created for the Cold War context when the US and USSR were pitted against one another. For Putin, NATO is now viewed not only with distrust, but as an international organization no longer serving the need of defense, but through inclusion of former Soviet states, an aggressive entity. As scholar Nikolay Murashkin argues, ““When facing accusations coming from the West, Moscow decision-makers can always counter by a map of numerous US/NATO military bases in countries around Russia, which certainly contribute to Moscow’s insecurity and perceptions about US-inspired regime changes, and, in turn, to another escalation spiral, rather than to the peace these bases claim to establish”” (Killalea, 2016). Putin even claimed that his actions in the Crimea were because of concerns that Ukraine would join NATO.

As Josh Cohen (2016) writes: “The West long underestimated the deep humiliation felt by Moscow as a result of NATO expansion toward Russia’s borders in the decades after the fall of the former Soviet Union, and even the United States Navy’s top commander in Europe admits Russia views NATO as an “existential threat” today. To make a historical analogy, Russia views NATO membership for Ukraine similarly to how U.S. President John F. Kennedy viewed the deployment of Soviet missiles to Cuba in 1962. Given that NATO was — and remains — a military alliance directed against Russia, dismissing Moscow’s feelings on this subject as merely “paranoia” is too simplistic.”

Therefore, academic scholars and journalists argue that if Ukraine were to be extended membership in NATO, Russia would react harshly. Speaking on this issue, professor Paul Dibb argues that ““The red line in the sand is if NATO makes Ukraine a member,” and that “That will be seen as a call for war”” (Killalea, 2016). Russia is adamantly opposed to the idea that Ukraine can belong within NATO.

While NATO may not say so directly, it seems that the international organization itself recognizes this. While Ukraine did apply for NATO Membership Action Plan in 2008, this plan was halted a couple of years later. More recently, some NATO country leaders have spoken on the likelihood (or lack thereof) of NATO accepting Ukraine in the foreseeable future.

However, Joshua Cohen (2016) argues that although the relationship between the United States and Russia is not well, “U.S. diplomats are hurting it further by sending conflicting messages about Ukraine’s future relationship with NATO.” For example, “NATO and Kiev signed a letter of intent in February for cooperation between their special operations forces. Two months later American ambassador and current NATO Deputy Secretary-General Alexander Vershbow said it was time to bring the Ukrainian military “in line with NATO standards.” Barely one week later, though, the U.S. Ambassador to NATO ruled out NATO expansion for the “next several years”” (Cohen, 2016).

Despite NATO’s power as an international military alliance, Cohen argues that they are unable to defend Ukraine against Russian interests, saying that “Russia has 270,000 troops and 700 jet fighters positioned on Ukraine’s southern and western borders. And as Russia demonstrated in 2015 when it sent 150,000 troops to surround Ukraine, Moscow can quickly mobilize its military in the event of a conflict.” Furthermore, he also argues that Russia’s buildup of troops on the Crimea is further evidence of the difficulty to defend Ukraine.

However, one could make an argument that NATO, if it chose, could still provide serious problems for Russia military. As Rasmussen et. al. (2014) point out, “Putin’s Russia is thus far less of a military, economic and political threat than the Soviet Union was. This comes not least to expression in NATO’s overwhelming military superiority… In a direct conventional confrontation, NATO would in all probability be able to defeat Russian forces” (9).

While this may indeed be the case, the issue with regards to NATO and the Ukraine becomes one of salience. How willing is NATO to defend Ukraine against Russia, knowing that more direct support could lead to further escalations in tensions? For NATO, Ukraine, while mattering, may not be as salient as the issue is to Russia.

Cohen asks as much, pointing out that for an American military leader, that have to ask themselves a number of questions as it pertains to NATO’s policy towards the Ukraine: He writes:

1. Would the United States be willing to back up a commitment to defend Ukraine by deploying tens of thousands of additional troops to Europe — essentially recreating a Cold War force posture on the continent?

2. How should Washington respond if — as is entirely possible — Moscow instigated further military action in Ukraine after Ukraine received an official invitation to join NATO, but before a formal agreement admitting Kiev to the club was signed?

3. Is the United States willing to strike command and control or military targets inside Russia proper if militarily required? How would it respond, then, if Moscow retaliates by launching missiles at Alaska or Europe, or by invading the Baltics?

4. And finally, is the United States willing to risk a nuclear exchange to defend Ukraine?

Thus, Russia has been able to act in ways that has not led to a direct military response by the West; “Russia has struck in places where Western interests and intentions were unclear and where its intervention did not justify a military response from the West. During negotiations in Geneva, Russia even acquired a diplomatic framework for its continued involvement in Ukraine on the pretext of intending to stabilise the situation” (9).

Concerns of a Nuclear War

It is this last point that has some other people worried about NATO’s relationship with Ukraine. It has been argued that another reason why NATO is reluctant to add Ukraine as a member is not merely a war with Russia (which, in and of itself is a problem), but also because of Russia’s nuclear arsenal. There has been debate on whether Russia would use its nuclear weapons in a war with Ukraine. But even if it does not do so, the mere possibility has been enough to worry scholars, given the damage that such weapons pose to the world.

Additional Concerns

While much of the relationship between NATO in Ukraine is to help the country from Soviet aggression, there are also concerns that Russia’s push eastward might also lead to additional breaches of sovereignty in other former Soviet States such as the Baltic countries. And “[w]hile an overt Russian attack against the Baltic states is highly unlikely, there are reasons for concern, given Putin’s emphasis on Russia’s responsibility to defend the rights of the Russian minority abroad” (Larrabee, Wilson, & Gordon, 2015). Thus, “Countries such as the Baltic states and Moldova, which are on Russia’s periphery and home to large ethnic Russian minorities, are worried that they could be the targets of this new Russian approach to warfare. In the future, NATO is likely to face Russian aggression that relies on approaches and techniques associated with Russia’s low-cost annexation of Crimea and the destabilization of eastern Ukraine” (Larrabee, Wilson, & Gordon, 2015: IX).

NATO and Ukraine References

Belkin, P., Mix, D.E., & Woehrel, S. (2014). NATO Response to the Crisis in Ukraine and Security Concerns in Central and Eastern Europe. CRS Report. July 31, 2014.

Cohen, J. (2016). Commentary: Why Ukraine’s NATO membership is not in America’s interest. Reuters. May 5, 2016. Available Online: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-ukraine-nato-commentary-idUSKCN0XW0V3

Killalea, D. (2016). Ukraine joining NATO would trigger war with Russia. News.com.au. August 15, 2016. Available Online: http://www.news.com.au/finance/work/leaders/ukraine-joining-nato-would-be-trigger-for-war-with-russia/news-story/a8c91f47dcf67b5877bbacd51c8132a5

Moon Cronk, T. (2016). European Reassurance Initiative Shifts to Deterrence. U.S. Department of Defense. July 14, 2016. Available Online: http://www.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/839028/european-reassurance-initiative-shifts-to-deterrence

NATO (2015). NATO-Ukraine relations: The background. June 2015.

Peterson, N. (2016). Putin Attacks Ukraine as NATO Bolsters Defense. Newsweek. July 14, 2016. Available Online: http://www.newsweek.com/putin-attacks-ukraine-nato-bolsters-defense-480017

Rasmussen, V.P et. al. (2014). The Ukraine Crisis and the end of the Post-Cold War European Order: Options for NATO and the EU. Centre for Military Studies. University of Copenhagen. July 2014, pages 1-38. Available Online: http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/english/publications/ukrainecrisis/Ukraine_Crisis_CMS_Report_June_2014.pdf

Sabitov, R. (2014). Crimean crisis through Russia–NATO relations’ perspective. Conference Paper. July 2014. Pages 1-9.

Shaheen, J. (2016). NATO and the EU aren’t going anywhere. CNN. September 23, 2016. Available Online: http://www.cnn.com/2016/09/23/opinions/nato-and-eu-still-have-faith-shaheen-opinion/

Trenin, D. (2014). The Ukraine Crisis And The Resumption of Great-Power Rivalry. Carnegie Endowment. Carnegie Moscow Center. July 24, 2014, pages 1-27. Available Online: http://carnegieendowment.org/files/ukraine_great_power_rivalry2014.pdf