Customary International Law

In this article, we shall discuss the issue of customary international law within international relations. Given the rising prevalence of international law in world affairs–not only today but for centuries (although it can be argued that international law has risen very quickly with the formation of the United Nations), it becomes necessary to understand the influence of customary law. Scholars argue that two types of law make up international law. The first type of law is agreements between States. This can be in the form of bilateral agreements, or multilateral agreements, and often is some form of treaty or convention. The second type of law is understood as custom, or customary international law (Rocha Ferreira, Carvalho, Gref Machry, & Vianna Rigon, 2013).

Customary law has a great deal of importance in society today. For example, one can see this related to the issue of international humanitarian law and international conflict, where “Customary IHL continues to be relevant in today’s armed conflicts for two main reasons. The first is that, while some States have not ratified important treaty law, they remain nonetheless bound by rules of customary law. The second reason is the relative weakness of treaty law governing non-international armed conflicts – those that involve armed groups and usually take place within the boundaries of one country. A study published by the ICRC in 2005 showed that the legal framework governing internal armed conflicts is more detailed under customary international law than under treaty law. Since most armed conflicts today are non-international this is of particular importance” ICRC, 2010).

Given the relevance of customary law, we are going to define international customary law, as well as provide examples of international law that has become customary law.

What is Customary International Law?

Customary law is the idea that law not codified, but that has been in practice for a long period of time can become binding law. Malcolm N. Shaw defines customary international law as the following: “Customary international law refers to international obligations arising from established state practice, as opposed to obligations arising from formal written international treaties. According to Article 38(1)(b) of the ICJ Statute, customary international law is one of the sources of international law. Customary international law can be established by showing (1) state practice and (2) opinio juris. Put another way, “customary international law” results from a general and consistent practice of states that they follow from a sense of legal obligation.”

The International Red Cross (2010) states that “Customary international law is made up of rules that come from “a general practice accepted as law” and that exist independent of treaty law. Customary international humanitarian law (IHL) is of crucial importance in today’s armed conflicts because it fills gaps left by treaty law in both international and non-international conflicts and so strengthens the protection offered to victims.”

When does something become customary international law?

This is one of the most difficult questions as it pertains to the topic of customary international law, and its not a problem that only faces us today. In fact, scholars and legal experts have tried to address this questions well before the most recent large evolutionary jump of international law following WWII. For example, “As it is possible to perceive in our time, medieval jurists did not agree on which acts were considered as customary. There were many debates concerning for how long or how many times an act should be practiced for it to be considered a custom. There was even some discussion on whether a judge should declare an act as a custom before it was considered law, what reminds us of the necessity of opinio juris that many scholars nowadays claim. Despite the relevant density of the debates, custom in the middle ages was, as a matter of fact, “not a defined thing but rather a more or less indeterminate set of possible conforming behaviors” (Kadens and Young 2013, 895). In other words, the idea of custom was used and manipulated to achieve a desired decision” (Rocha Ferreira, Carvalho, Gref Machry, & Vianna Rigon, 2013, 183).

Scharf (2014) points out that “By tradition, jurists, statesmen, and scholars have looked exclusively to two factors to define whether an emergent rule has attained customary international law status: 1) widespread State practice and 2) manifestations of a conviction that the practice is required by international law” (although he notes that there are also other matters to address when looking at international customary law).

History of Customary International Law

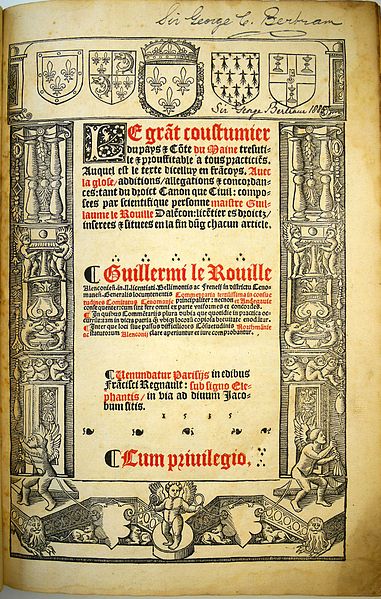

Customary law is said to have existed in some form or another for centuries. There have been many historical references to the idea of additional law not directly included in formal agreements. For example, Batolus de Sassoferrato (1313-1357) wrote about customary law: “A statute obtains [its] consent expressly, and therefore does not require other conjectures [about its existence]. But custom requires tacit [consent]. Therefore a long passage of time is necessary, so that [the custom] may become apparent through the consent of the people and their perseverance [in the act]” (Kadensand Young 2013, 889-890)” (in, Rocha Ferreira, Carvalho, Gref Machry, & Vianna Rigon, 2013: 183).

There are many examples of customary international law. For example, the International Court of Justice, in its history of the formation of the ICJ, says that

The creation of the Court represented the culmination of a long development of methods for the pacific settlement of international disputes, the origins of which can be traced back to classical times.

Article 33 of the United Nations Charter lists the following methods for the pacific settlement of disputes between States: negotiation, enquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement, and resort to regional agencies or arrangements; good offices should also be added to this list. Among these methods, certain involve appealing to third parties. For example, mediation places the parties to a dispute in a position in which they can themselves resolve their dispute thanks to the intervention of a third party. Arbitration goes further, in the sense that the dispute is submitted to the decision or award of an impartial third party, so that a binding settlement can be achieved. The same is true of judicial settlement (the method applied by the International Court of Justice), except that a court is subject to stricter rules than an arbitral tribunal, particularly in procedural matters.

Mediation and arbitration preceded judicial settlement in history. The former was known in ancient India and in the Islamic world, whilst numerous examples of the latter are to be found in ancient Greece, in China, among the Arabian tribes, in maritime customary law in medieval Europe and in Papal practice.

There are many other examples of customary international law. In fact, a great deal of formalized international law actually began as some form of customary international law. In addition, it has often been institutionalized courts that have worked with understanding and better defining customary international law. For example, this can be seen with early international courts such as the League of Nations’ Permanent Court of Justice, and then later the United Nations’ International Court of Justice. Scholars note that “The jurisprudence of the ICJ and also of its predecessor, the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ), has helped to clarify many issues concerning the formation of customary international law, in cases such as the Lotus (1927), the Asylum (1950), the North Sea Continental Shelf (1969) and the Nicaragua (1986) cases” (Rocha Ferreira, Carvalho, Gref Machry, & Vianna Rigon, 2013: 182-183) (however, that the same scholars also say that “in the last decade, the Court has not made much progress in several topics concerning custom, keeping a very cautious behavior in ascertaining the existence of customary norms. For instance, the Court avoided pronunciation about issues as the customary character of universal criminal jurisdiction, the legal status of United Nations General Assembly Resolutions and others topics that concern scholars and the legal international community. It is possible to perceive that, despite the long history of custom, it still gives rise to debate” (Rocha Ferreira, Carvalho, Gref Machry, & Vianna Rigon, 2013: 183).

However, we should also point out that it is far from a consensus that international codified law (through conventions, treaties, etc…) takes precedent over customary international law. For example, Michael Wood, Special Rapporteur of the International Law Commission (ILC) states that

“Even in fields where there are widely accepted “codification” conventions, the rules of customary international law continue to govern questions not regulated by the conventions and continue to apply in relations with and between non-parties. Rules of customary international law may also fill possible lacunae in treaties, and assist in their interpretation. An international court may also decide that it may apply customary international law where a particular treaty cannot be applied because of limits on its jurisdiction (for example in the Nicaragua case)” (ICJ and Customary International Law).

Also, it becomes evident that various international treaties turn into customary international law. There are many examples that help illustrate this point. Tunkin (1993) argues that one look no further than multilateral treaties. These treaties, while they are usually binding on just those states who have signed and ratified said treaties, can take on a customary law status. Tunkin (1993), speaking on this issue, writes: “Think, for example, of the Briand-Kellog Pact of 1928 that prohibited the recourse to war. This norm abrogated the right to States to wage war that had existed in international la for centuries, and had become a norm of international law before the beginning of World War II. It was a historic change in general international law effected by an international treaty” (538).

However, this is far from the only international law document that has evolved to international customary law. For example, that the highly influential United Nations Charter. This document (and the United Nations as a whole) arose out of the events preceding and then during World War II. Tunkin (1993) argues that the United Nations Charter “went much further than the Briand-Kellog Pact by introducing the prohibition on the use and threat of force in relations among States, and many other innovations” (538).

Another United Nations document that has further illustrated the power and influence of international customary law is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This document, signed in 1948, set the tone for the international human rights law movement. This document is one of the most noted international customary law documents. Countries throughout the world have not only cited the document, but some have used parts of it in their own state documents (such as constitutions). This document has been understood to have international influence, even thought it itself began as non-binding.

Continued Debate on the Influence of International Customary Law

One of the lingering questions on the topics of international customary law is whether customary law matters today, and also how impactful it is in international law. There are various criticisms by scholars of customary international law, whether because it is difficult to understand, to navigate, or because it has been over-ridden by traditional international law. In addition, some have suggested that since there is no official legal backing for customary international law, it can be difficult to prove it worth as part of international law (Guzman, 2005).

Yet, there have been arguments by international legal scholars to not only offer their own theories on the value of customary international law (Guzman, 2005), but legal thinkers have also illustrated–through various historical legal examples, the value of customary law For example, Guzman (2005) looks at international customary law from the position of rational choice. He does argue that customary international law, like non-customary international law, is difficult to enforce. But again, this is not limited only to customary international law. The penalties, as well as repetitional costs of violating customary law, or international law, are both real.

Despite the fact that binding international law has developed greatly in the past 70 years, thus arguably taking a lot of influence from international customary law, customary law itself continues to be influence in international relations. Scharf (2014) makes three points about how international customary law still holds great weight in international affairs. He says:

- “First, in some ways, customary international law possesses more jurisprudential power than does treaty law. Unlike treaties, which bind only

the parties thereto, once a norm is established as customary international law, it is binding on all States, even those new to a type of activity, so long as they did not persistently object during its formation. Since some international law rules co-exist in treaties and custom, customary international law expands the reach of the rules to those States that have not yet ratified the treaty. In addition, the customary international law status of the rules can apply to actions of the treaty parties that pre-dated the entry into force of the treaty.

- Scharf (2014) also says that “Second, while one might tend to think of customary international law as growing only slowly, in contrast to the more rapid formation of treaties, the actual practice of the world comm unity in modern times suggests that the reverse is more often the case. For example, negotiations for the Law of the Sea Convention began in 1973, the Convention was concluded in 1982, and did not enter into force until it received its sixtieth ratification in 1994—a period of twenty-one years.”

- Another point that he makes is that customary international law is actually quite clear, despite false beliefs that treaties are always clearer about the law. In fact, he says that “customary rules may provide greater precision since they evolve in response to concrete situations and cases, and are often articulated in the written decisions of international courts” (310).

Resources on Customary International Law

There are great resources on the topic of customary international law. We have linked out to a few of these sources, either to the source directly, or to an amazon page, where you can purchase a copy of the reference.

International Committee of the Red Cross: Customary Law

Michael Scharf: Customary International Law in Times of Fundamental Change

Hugh Thirlway: The Sources of International Law

Below, we have also cited a very detailed and interesting panel discussion on international customary law.

Customary International Law References

Guzman, A.T. (2005). Saving Customary International Law. Michigan Journal of International Law, 115, pages 116-176. Available Online: http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1631&context=facpubs

International Committee of the Red Cross (2010). Customary International Law. 29-10-2010. Available Online: https://www.icrc.org/eng/war-and-law/treaties-customary-law/customary-law/overview-customary-law.htm

Scharf, M.P. (2014). Accelerated Formation of Customary International Law. Faculty Publications, Paper 1167. Available Online: http://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2166&context=faculty_publications

Shaw, M.N. (2003). International Law, Fifth Edition. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Available Online: https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/customary_international_law

Tunkin, G. (1993). Is General International Law Customary Law Only? European Journal of International Law, 4, pages 534-541. Available Online: http://ejil.org/pdfs/4/1/1216.pdf